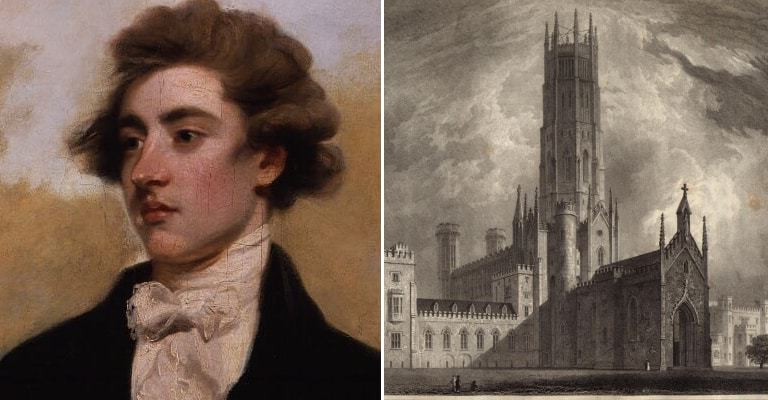

Between 1796 and 1813, one man doggedly pursued the building of the tallest edifice in Britain, despite the phenomenal cost of the enterprise and the tower falling down shortly after its first completion. The place was Fonthill Abbey, the home of William Thomas Beckford (1760-1844), the richest man in Britain. At its peak (before falling down), the tower of Fonthill Abbey stood at 91 metres, providing a visible landmark to Beckford’s immense wealth, profligacy and eccentric tastes. However, in pursuing so lavish a lifestyle Beckford ran into understandable financial difficulties, and had to sell the estate in 1822.

To understand the story of Fonthill Abbey, we must first understand the only man in the world who wanted it built, Beckford himself. Born at his family’s London residence in 1760, Beckford’s father was twice Mayor of London, and had accumulated a fabulous fortune through property, sugar plantations, and the cloth industry. His father’s wealth meant that the young William had only the finest education, and was widely-read in the Classics, foreign languages, physics, literature and philosophy. At the age of 10, his father died, leaving Beckford with £1 million (the equivalent of £125 million or $175.5 million today).

An only child, his inheritance also left Beckford with a vast annual income and the 6, 000 acre estate of Fonthill in Wiltshire. Beckford’s piano teacher was rumoured to have been Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart himself, and he was tutored in drawing by the prominent landscape painter, Alexander Cozens. To say that the boy grew up spoilt would be an understatement, and soon Beckford was committed to a life of self-indulgence and feeding his epicurean appetite for culture. For instance, he travelled Europe for fifteen-years accompanied by an entourage including his doctor, a baker, a cook, and twenty-four musicians.

Beckford was not content simply to accept the lavish accommodation on offer when he visited a new place. He would regularly have rooms repapered for his arrival, used only his own cutlery and plate, and once had a flock of sheep imported from England to improve the view where he was staying in Portugal. Whilst travelling, Beckford also built up an incredible collection of art. He had a particular fondness for Italian Quattrocentro paintings, which melded medieval and Renaissance styling, as well as Oriental art, buying the first piece of Chinese porcelain documented in Europe, The Fonthill Vase.

Beckford was bisexual, and was persecuted for his affair with William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon. The pair met when Beckford was 19, and Courtenay 10, and at some stage their intense friendship blossomed into romance. Seeing each other frequently at the Fonthill estate and Powderham Castle, the scandal came to light when love letters were intercepted and cruelly revealed in the national press by Courtenay’s own uncle, Lord Loughborough. Beckford was pressured by his family into marrying Lady Margaret Gordon, in what turned out to be a happy alliance, and the scandal forced him to go on his aforementioned-travels.

Aged just 21, Beckford wrote the Gothic novel Vathek: An Arabian Tale, demonstrating his great learning by doing so in French. Evidencing his great love of Orientalism, Vathek tells the tale of the titular Caliph, who renounces Islam to gain supernatural powers, assisted by his mother, Carathis. Vathek’s attempts to gain powers include the sacrifice of fifty children and others angered by the infanticide, the conjuring of spirits in a graveyard, and mixing serpents’ oil with powdered Egyptian mummies. Instead of succeeding, the novel ends with Vathek being dragged to hell and ‘wandering in an eternity of anguish’.

Many critics see Vathek as semi-autobiographical. The Caliph is immensely wealthy and, like Beckford, comes to inherit his father’s wealth and power at an early age. Vathek is similarly well-educated to his creator, with a great intellectual curiosity that is fed by his riches. We also see a thinly-veiled portrait of Courtenay as Gulchenrouz, an effeminate young man with a penchant for cross-dressing, who is rescued from Carathis and ascends to heaven. Tellingly, Vathek also constructs a huge tower, in his case to study astronomy and learn the secrets of heaven, anticipating Beckford’s own architectural activity at Fonthill Abbey.