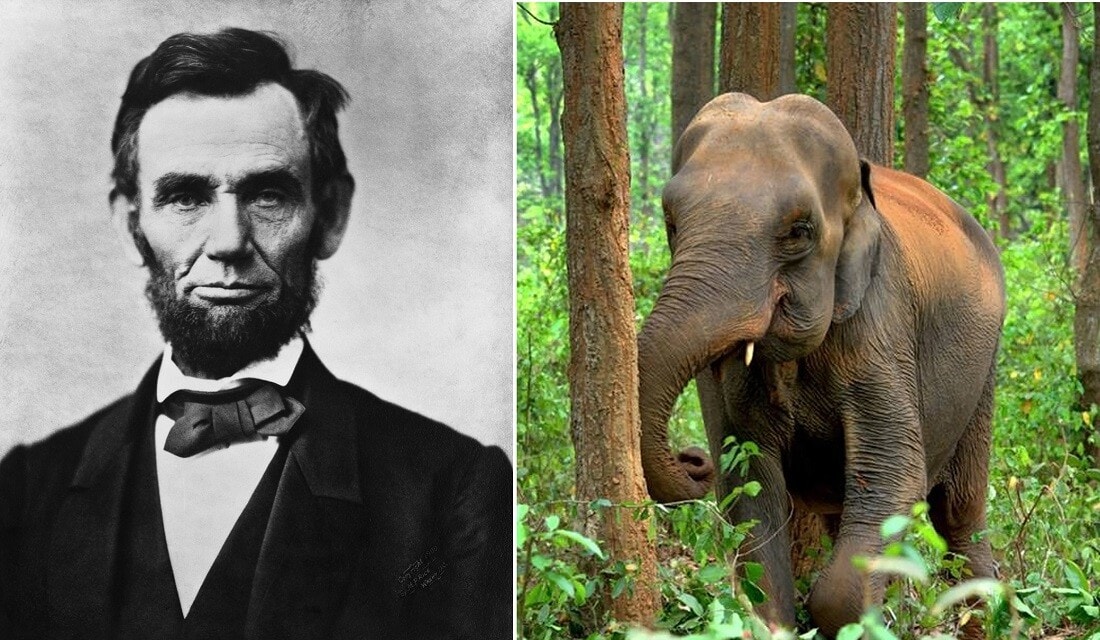

America could have had herds of wild elephants roaming its wilderness today. To the dismay of pachyderm lovers, however, it never came to be, because of a decision by President Lincoln. Thanks a lot, Honest Abe. Below are twenty five things about that and other fascinating but lesser known decisions and events that shaped America and impacted the lives of prominent Americans.

The Real Life King from The King and I Offered to Populate America With Elephants

Other than in his home country, relatively few people these days know of King Mongkut, titled Rama IV of Siam. Of those who recognize the name, most probably recall it as that of a character in The King and I, a 1950s musical remade into a movie about his (fictionalized) relationship with English governess Anna Leonowens. Rama IV (1804 – 1868) was actaully a real life nineteenth century monarch who ruled Siam, now Thailand, from 1851 until his death in 1868.

A modernizer, King Rama IV opened his kingdom to Western influences, and initiated the cultural and technological modernization of Siam. So much so that he became known as “The Father of Science and Technology” in his country. His modernization held off Western encroachments – at least temporarily. He sought recognition as an equal among the world’s rulers, and corresponded with many of them. As seen below, in one of those correspondences with a US president, he offered to populate America with herds of elephants.