Fraud, embezzlement, con-artists, there is nothing new about any of them. In 193 AD, the Roman Empire was sold to the highest bidder by the Praetorian Guard, and the ill-fated Emperor Didius Julianus enjoyed its ownership for a blissful nine weeks, before the fraud fell apart and he went the way of a great many Roman emperors. Fraud has not always been perpetrated for financial gain. Everything from geographic discovery to educational attainment, from religious belief to political power has at one time or another been the subject of deception or manipulation.

Fraud, of course, depends in large part on the credulity of the victim, or victims, but it also demands much skill and virtuosity on the part of the fraudster. That is probably why everybody loves a tale of a well executed, elegantly conceived scam, assuming, of course, that the victim is someone else, and in particular someone deserving of ignominy of being duped. Here is a list of some of the most creative, brazen and successful fraudsters, con artists and scam merchants in history, and some of their more imaginative escapades. We are quite sure that there are many others worth mentioning, but these are the Top Ten.

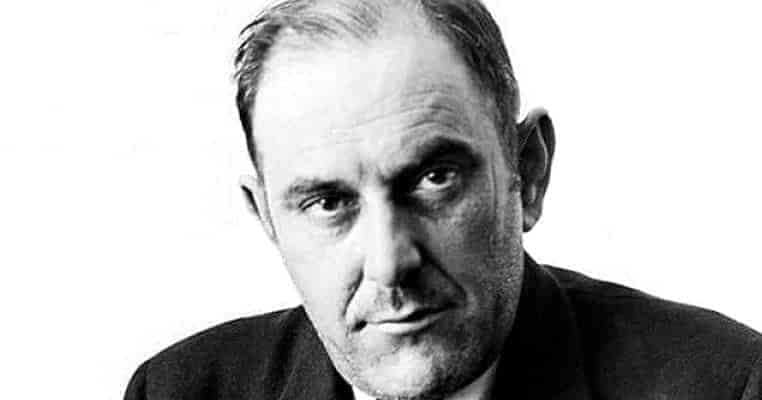

William Chaloner

William Chaloner in probably better known for who finally caught him than the frauds he perpetrated. Forgery was his game, and the great Isaac Newton his nemesis.

The story begins in the 1650s, with the birth to an impoverished Warwickshire weaver of a son. The child grew into a willful youth with dishonest tendencies, prompting his despairing father to apprentice him to a Birmingham nail maker.

Birmingham at the time was the center of a thriving, and illegal cottage industry in the counterfeiting of ‘groats’, an ancient silver-based coin valued at four old pence. The counterfeit version was heavily adulterated with iron, and usually it entered circulation without raising too many eyebrows. Counterfeiting was a risky business, however, with punishments ranging from hanging to burning at the stake, and graduating from forging the humble groat to the more lucrative, and dangerous French Pistoles and English gilded guineas took daring, and considerable skill.

By then William Chaloner was working in the thriving counterfeit industry of London, and growing wealthy at it. In the 1670s he purchased a large country estate, moving his minting process out of earshot of the law. The main risk was in the passing of fake coins into circulation, and for this he hired middlemen, who were not infrequently caught and hanged. The fact that Chaloner himself remained one step ahead of the law is fair testimony to what a slippery character he was.

Then, in 1696, the great English physicist, Sir Isaac Newton, after a long and spectacularly successful career, accepted the position of Warden of the Royal Mint. English currency was moving towards notes and paper money, and needless to say, William Chaloner wasted no time in applying his skills to this. He had numerous narrow escapes, but avoided punishment simply because the development of paper money was in advance of any laws procreated to outlaw its forgery. He was, however, now firmly in the crosshairs of the establishment, and leading that establishment was Sir Isaac himself.

What followed was a carefully stage-managed cat-and-mouse game between two highly intelligent men. Chaloner, however, had left behind him a long paper trail of arrests and indictments, all of which he had slipped through or wriggled out of, but which collectively painted a picture of a long career outside the law. Unfortunately also, the canny forger had paid for his freedom many times by selling-out fellow counterfeiters, and among those that had escaped the gallows, Sir Isaac was able to gather together many prepared to point the finger.

William Chaloner was arrested and brought to trial, facing the testimony of old enemies, and the widows of many others who had swung. Newton presided over the hearings, and the notorious hanging judge Sir Salathiel Lovel brought the hammer down on a guilty verdict, and a sentence of death.

Feigning madness, wheedling and conniving, attempting blackmail and simple pleas for forgiveness, William Chaloner was marched to the gallows March 22nd 1699, and thus the long and lucrative career of a master forger thus came to an end.