Medieval literature is by far the least popular aspect of English Literature degrees worldwide. Usually studied only when mandatory, it is hard for lecturers (in this author’s experience) to drum up much interest from students expecting to spend their degree reading Shakespeare and Wordsworth. Medieval literature is hard work: its great age makes it difficult to understand at first, and on a degree programme usually requires learning a new extinct language. Students who apply themselves, however, find a vast and varied corpus with prescient themes, unsurprising given that what is known as the ‘middle ages’ spans around 1, 000 years.

It is a paradox that, although medieval history continues to intrigue, the literature of the period is largely ignored. However, as Cicero said, the library is the ‘soul of the house’, and so we can learn much about the people who lived through the tumultuous millennium of battles, religious change, and conquest. This list of the dozen best literary works of the period is necessarily subjective, and is also confined to texts with available modern translations. That said, it is hoped that the items on the list will give readers a useful introduction into the bounteous treasures of medieval literature.

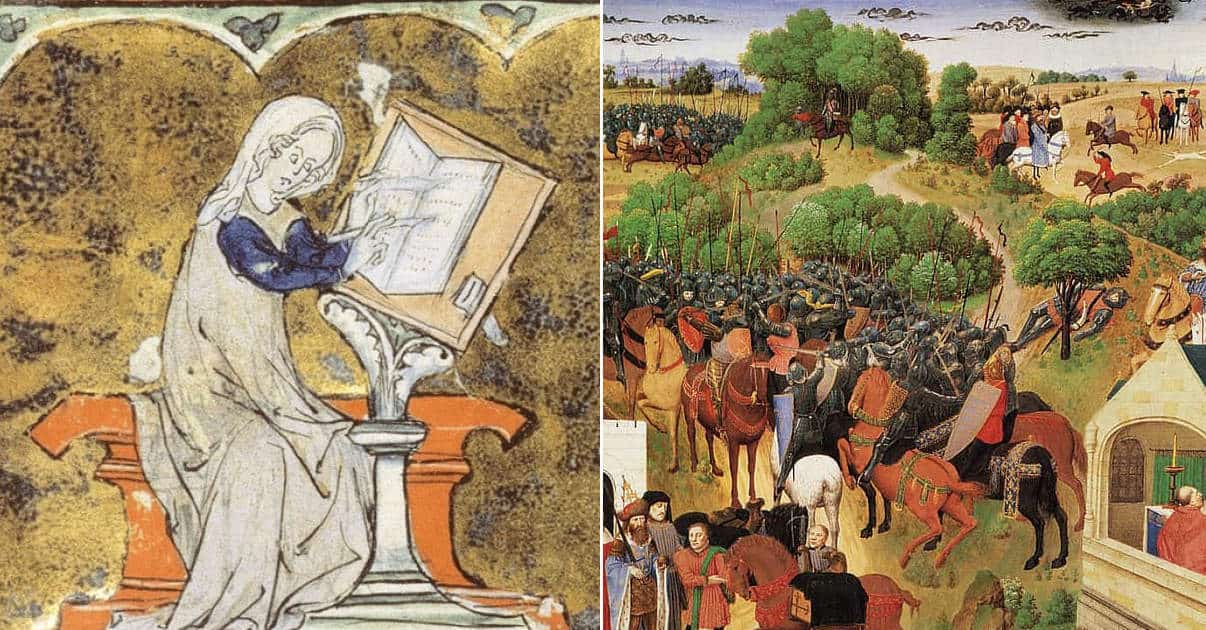

Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

Geoffrey Chaucer (c.1343-1400) must rank as one of history’s greatest polymaths. He was an astronomer, civil servant, diplomat, philosopher, and writer. His knowledge of chemistry meant that he was still being cited as a source for alchemy centuries after his death. His literary output is of such consistently-high quality that any one of his surviving works could justifiably be placed on this list; The Canterbury Tales is included for its variety, and number of translations. Perhaps his greatest achievement was to raise the English language to the status of French and Latin in literature, paving the way for others.

The Canterbury Tales is a selection of stories told by character-narrators within the frame-narrative of a pilgrimage to St. Thomas à Becket’s shrine at Canterbury Cathedral. The genres range from lofty epic and romance to Breton lais, didactic literature, and even fabliaux (bawdy tales with obscene climaxes). Even the General Prologue, in which the characters are introduced, belongs to a popular genre of the fourteenth century, the estates satire (a mockery of the various classes). Each of these genres are parodied and satirised through Chaucer’s devastatingly accurate mimicry, his ability to write in so many genres demonstrating his inestimable skill.

So much more than just literary genres are mocked: every character’s class is scrutinised and lampooned, from the lowly Reeve to the Knight. Even Chaucer himself does not escape parody: he appears as a pilgrim and narrator in The Canterbury Tales, and his first attempt at telling a story is so poor that he is stopped mid-flow by the churlish innkeeper, Harry Bailey. There is nuanced interplay between the tales told and their narrators, brought about through the inclusion of the General Prologue. For example, the Pardoner’s deceitful character is at troublesome odds to the wonderful moral yarn he spins.

The Canterbury Tales have a continuing relevance to today’s society. See, for example, the depiction of inflexible honour and warfare in the Knight’s Tale, the corruption of the clergy in the Summoner’s Tale, and the all-consuming sexual jealousy of the foolish Januarie in the Merchant’s Tale. As a whole, the pilgrim-narrators stand as both a celebration of the diversity of people and a warning against judging others too quickly: important lessons which today’s world leaders would do well to learn. The pilgrimage itself serves as an allegory for the journey of life, as we all head towards a promised land.

Given its masterful range of genres, there really is no better introduction to medieval literature or society. In its time, The Canterbury Tales was one of the most popular texts, based on the number of manuscripts of it that survive. It offers an invaluable and satirical snapshot of England at the crucial period of the late 14th-century: having survived the Black Death and the Peasant’s Revolt, the country was heading towards the usurpation of King Richard II and a slide into the Wars of the Roses. Timeless relevance, literary excellence, and historical context all make The Canterbury Tales essential reading.