If a terrorist is defined as someone who uses violence and intimidation as a means of pursuing political aims, the Roman senator Catiline must surely be classified as one. Lucius Sergius Catalina, also known as Catiline, is infamous for his role in a conspiracy to overthrow the Roman Republic in 64 BC. It came at a time when the Republic was in its death throes and could also be classified as Cicero’s finest hour as the great orator luxuriated in his title ‘Savior of Rome.’

Background

Catiline was an unscrupulous career politician known for having an unstable character, yet he also possessed a magnetic charm which helped him climb the political ladder. It also lured women to his side, although sources suggest he murdered his first wife and child (as well as his brother-in-law in 81 BC).

His attempts to succeed in the consular elections failed several times and eventually, Catiline decided to seize power by illegal means. There are suggestions that he was involved in a plot to kill Senators in 65 BC (in what is known as the First Catilinian Conspiracy) but historians can’t find evidence linking him to the plan.

On the surface, he was an ideal candidate for the consulship because of his military background. At one time he even had the support of Julius Caesar. However, he courted controversy wherever he went. While working as governor in Africa, Catiline was charged with extortion, and while he was acquitted, the trial damaged his reputation. Rumors surrounding the mysterious death of his wife and son also burdened him.

Nonetheless, Catiline won the support of the wealthy and influential Crassus as he ran for consul in 64 BC. Again, he suffered defeat as Cicero, and Gaius Antonius Hybrida were victorious. After this setback, Crassus and Caesar withdrew their support for Catiline because he revealed a desire to embark on a revolutionary program that was contrary to Crassus’ belief system.

However, there were plenty of supporters for Catiline’s radical ideas as desperation amongst certain elements of society was rife. The public was tired of corruption, and when it came to Italian farming, the situation was desperate since the land was destroyed due to industrialization and war. Catiline promoted his debt relief policy and gained support among the poor and from many of Sulla’s veterans.

An Atmosphere of Fear

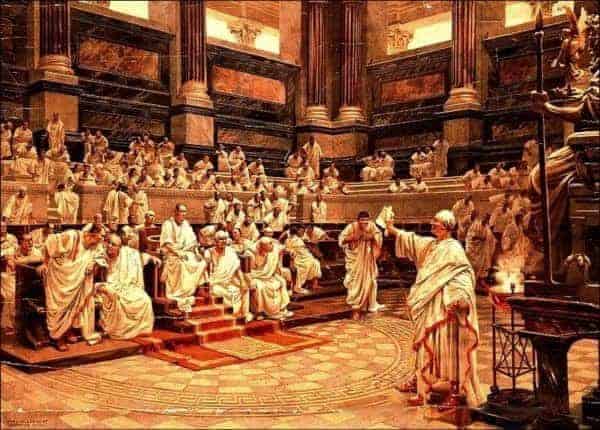

Cicero took his office as consul along with Hybrida on January 1, 63 BC. He heard rumors of a conspiracy which would involve the murder of several government officials (including Cicero) and the burning of Rome. This information came from a woman called Fulvia who was a mistress of Quintus Curius, one of Catiline’s friends.

According to her story, Curius was heavily in debt and to prevent his mistress from leaving him; he claimed he would be coming into money and then revealed details of the plan. Fulvia told Cicero’s wife who informed her husband. However, very few people believed the consul because there was little evidence of a plot barring rumor. Instead of listening to the Senate, Cicero became convinced there was a conspiracy and soon enough, the great orator found the evidence he needed.