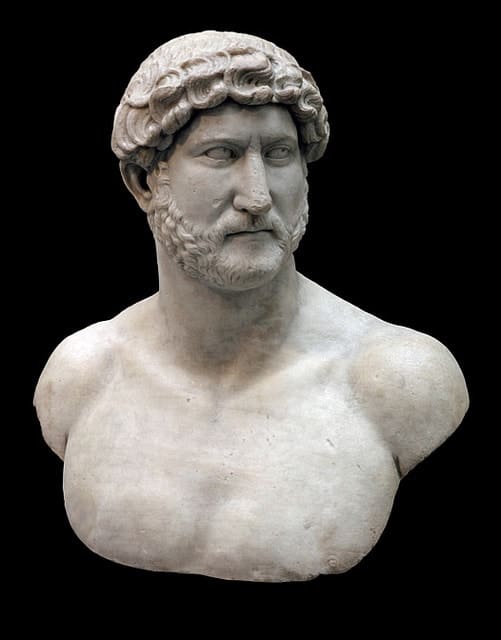

Emperor Hadrian ruled the Roman Empire from 117 AD to 138 AD and is deemed to be one of the best Roman emperors of all time. As well as building the famous Hadrian’s Wall in Britain, he rebuilt the Pantheon and ordered the construction of the Temple of Venus and Roma. While the Empire reached its peak in term of expansion under Trajan, Hadrian withdrew from several of his predecessor’s conquests including Assyria, Armenia, and Mesopotamia.

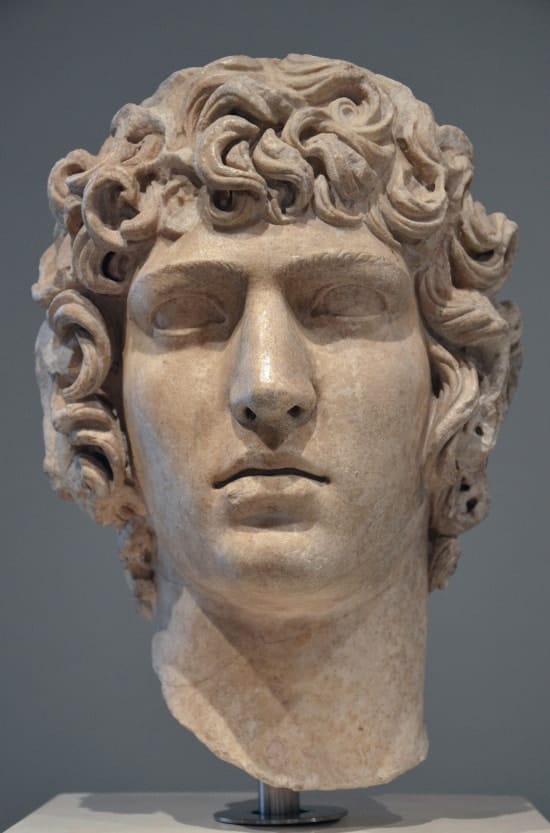

Hadrian is also known for his favoritism towards a young Bithynian Greek named Antinous who became the emperor’s lover. Little is known about Antinous’ early life although he was probably born in modern-day Bolu in Turkey. It is likely that he was introduced to Hadrian in 123 before traveling to Italy to receive further education.

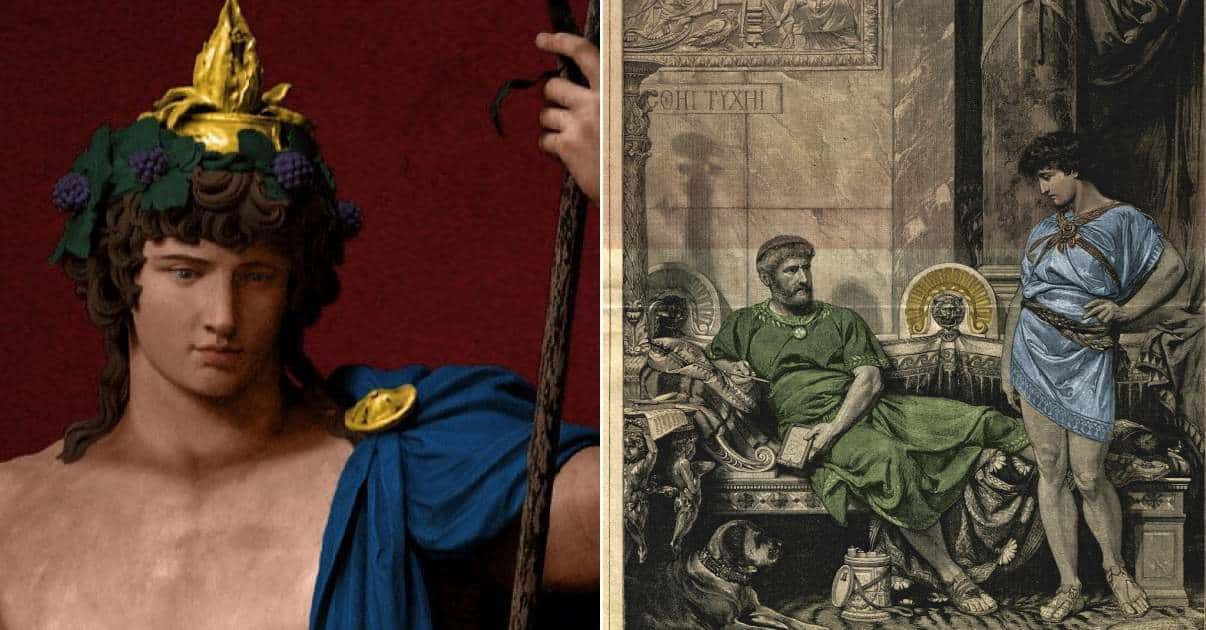

Over the next few years, the two became lovers, and Antinous became Hadrian’s favorite sometime in 125. According to historian Royston Lambert, Antinous was “the one person who seems to have connected most profoundly with Hadrian.” The two traveled together on a tour of the Empire with Antinous part of the emperor’s personal retinue. When the young man died in 130, the emperor was heartbroken and deified his young lover. This cult was devoted to the worship of Antinous and spread throughout the Empire.

Antinous & Hadrian’s Story

In the modern era, a sexual relationship between a grown man and a boy is obviously illegal, but at the time of Hadrian, sexual relations between adult males and boys had been deemed socially acceptable for centuries in Greece. Older men (known as erastes) were aged between 20 and 40, and they would engage in a sexual relationship with boys (known as eromenos) who were usually between 12 and 18 years old. The adult would care for the boy and play an important role in their education.

In the Roman Empire, bisexuality was common by the second century AD so there wouldn’t have been any open objection to the relationship between Hadrian and Antinous. The emperor met Antinous in 123 or 124 in the young man’s hometown of Claudiopolis (Bolu) and was probably attracted to him due to the boy’s perceived wisdom. The duo both enjoyed hunting, and it is known that the emperor wrote erotic poetry and an autobiography about his young favorites; it is likely that Antinous was the subject of these writings.

The duo traveled together through Italy’s Sabine region in March 127, but for the next two years, Hadrian was struck down by an unexplained illness. Nonetheless, he embarked on another tour, this time to North Africa, and once again, his young lover was in tow. They settled in Antioch in June 129 and set up a base there. Then the duo went to Syria, Arabia, and Judea.

In 130, they went to Alexandria and visited Alexander the Great‘s sarcophagus. While the emperor was welcomed, the Hellenic elite, angered with some of Hadrian’s actions, began to gossip about his sexual activities. While in Libya, it is claimed that the emperor saved Antinous’ life as they encountered a Marousian lion that was causing problems. If Hadrian thought his actions would prolong their relationship for many years, he was sorely mistaken.