Despite the name, the Hundred Years’ War between England and France actually lasted 116 years (1337-1453). It was an intermittent conflict which involved a number of disputes; most notably the legitimate successor to the French Crown. Overall, five generations of kings from Britain and France fought over the right to rule what was the most powerful kingdom in Western Europe at the time.

The background to the war goes back to William the Conqueror’s victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. He united England with Normandy and ruled both kingdoms. By the reign of Henry II, England owned a huge tract of land within France, and subsequent kings found it almost impossible to control. Edward III became king in 1327, and by that stage, England only controlled Ponthieu and Gascony in France.

Charles IV of France died in 1328, and he had no male heirs. His sister, Isabella, was Edward III’s mother, so the English king believed he had the right also to rule France. However, Charles’ cousin became King Philip VI of France instead. Edward was furious but appeared to accept the decision. However, when Philip took Guyenne in 1337, Edward launched his bid to become the new French king. Guyenne was a fief of the French crown but technically belonged to the English. Edward raised an army and the Hundred Years’ War began. In this article, I look at five key battles in the conflict.

It is important to note that the conflict was very much a series of interconnected wars with a number of truces in between. Neither nation had an army constantly in the field, and there were periods of peace that lasted several years. Although the English had the superior army, they somehow lost; probably due to the lack of a strategic plan and the inability to press home an advantage.

1 – Battle of Crecy (1346)

English inaction and French raids on towns on the southeast coast of England marked the first few years of the war. The British Navy enjoyed the first significant victory at the Battle of Sluys in 1340 which caused the French raids to cease for a time. The next few years were marked by the War of the Breton Succession where Philip backed Charles of Bois and Edward backed John of Montfort.

The next major battle happened in 1346 when Edward left Portsmouth with 750 ships and 15,000 troops on July 12. The English landed at Normandy and proceeded to raid the countryside until Philip intervened with an army of up to 30,000 men. The Battle of Crecy took place on August 26 and was a complete disaster for the French despite their significant numerical advantage.

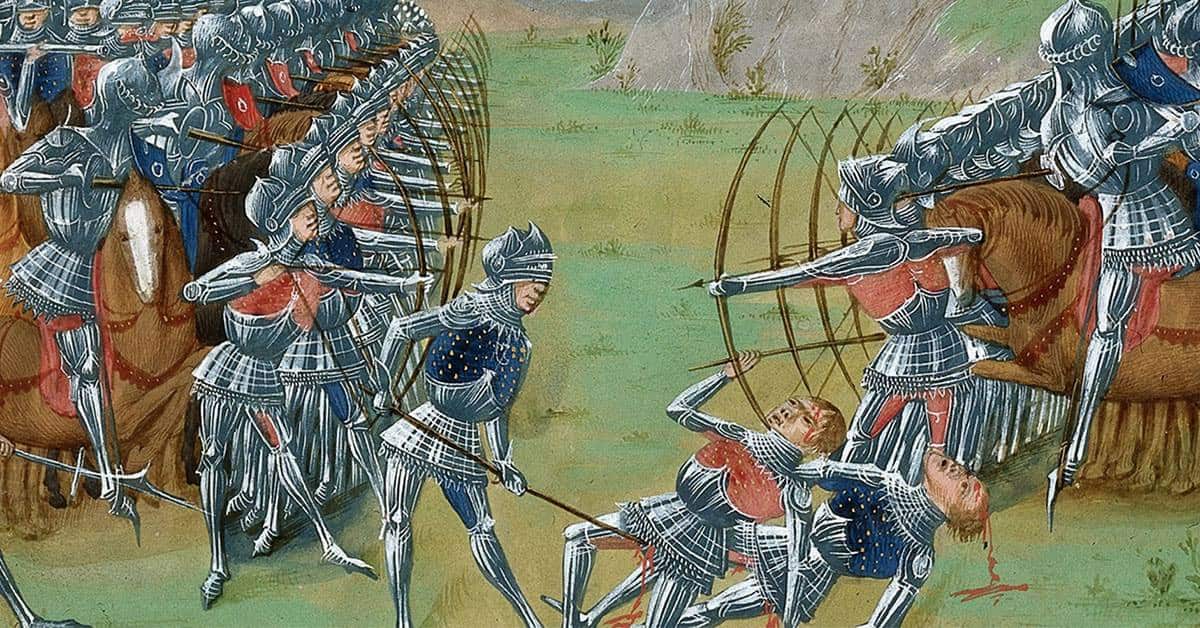

Philip’s Genovese crossbowmen were no match for the English longbowmen who were much quicker when it came to firing and reloading. The Genovese retreated and the French knights charged against the English infantry. The assault was an utter failure as the English lines refused to budge under pressure. It was soon apparent that the French had no real strategy beyond basic charges and when the English archers moved forward and began firing, the French horsemen were annihilated.

The few knights that made it to the English lines were killed in fierce close combat. There were approximately 15 failed French attempts to attack, and they finally withdrew when there was no hope of victory. At the end of the battle, Philip’s brother Charles was dead along with a number of allies, 1,500 knights and up to 14,000 men in total. In contrast, the English army lost no more than 200 men. Philip appealed to the Scots for help, but King David II of Scotland was defeated by the English at the Battle of Neville’s Cross on October 17, 1346.

At the time, it was one of the most decisive battles in Western European history. It signaled the end of the era of the heavily mounted knight and started a new focus on infantry. Despite the significance of the victory, Edward did not immediately press home his advantage. He marched forward and took Calais in 1347, but overall, progress through the French countryside was slow.