Simply put, the Lost Cause of the Confederacy, which began in the aftermath of Reconstruction, is the presentation of the belief that Southern secession was legal, just, and a reflection of the true values of America’s Founders. Its proponents suggest the Constitution was a contract, and that the parties involved could legally withdraw from the contract based on the will of the people within the states. Its rise coincided with and supported the enactment of laws in the South legalizing segregation and denying voter’s rights. It flourished again as America entered World War I, in the run-up to World War II, and during the Civil Rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s.

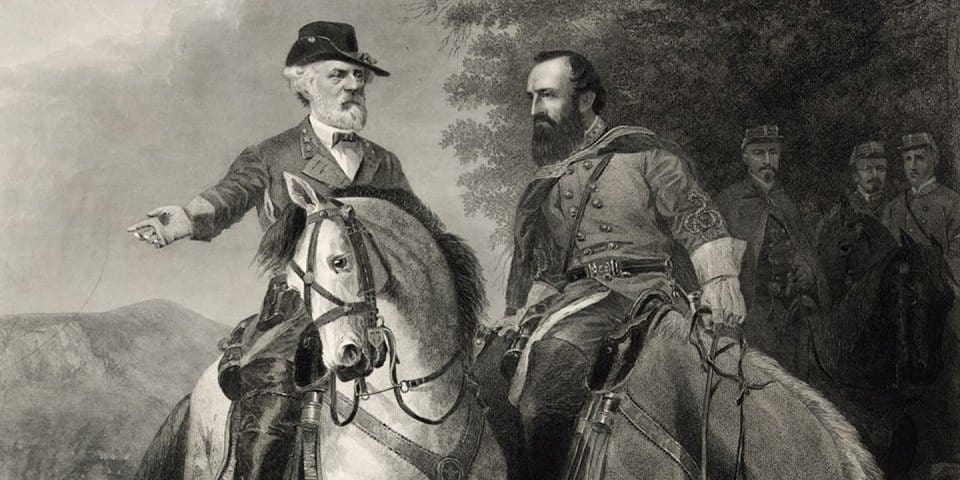

Supporters of the viewpoints presented in the Lost Cause movements led to the creation of a false Southern “legacy”. The film Gone with the Wind presented it in an onscreen introduction describing, “Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and Slave”. The film supported a legacy created during the Lost Cause period, along with monuments to Southern leaders which reflected nobility and moral courage. No less a personage than Robert E. Lee, arguably the Confederacy’s greatest hero, opposed the creation of such monuments. He believed such monuments, and even the preservation of battlefields for posterity, created continued strife, and that it was “wiser not to keep open the sores of war”. Here is the story of the Lost Cause pseudohistory, and its creation of memorials and monuments which still divide the nation.

1. The Lost Cause rooted in the antebellum arguments justifying slavery and secession

Before the Civil War, slavery presented the most divisive issue in the United States. It also existed as the root of the Southern economy. Production of cotton, tobacco, and rice for export to European markets offered the South its greatest source of income. In the pre-industrial South, all three relied on slave labor to be profitable. As the southern states found their influence in the Congress declining, their legislators, particularly their Senators, argued the states had the right to nullify federal laws which had an adverse impact upon them. Failing that right, they argued they had the right to vacate the contract which was the Constitution. Their most vocal argument was that the very Constitution they wanted to exit guaranteed the institution of slavery.

Antebellum arguments, especially by men including South Carolina Senator and one-time Vice President John C. Calhoun, expressed the view that enslaving the black race was a Christian duty. They argued that those held in slavery were inestimably better off than those remaining, in their view, in darkness in Africa. They also espoused the view that blacks were incapable of fending for themselves in society, and were completely dependent on the beneficence of their owners for their survival. First appearing in 1866 as the title of a work on the war by Virginian Edward Pollard (The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates), the movement denied slavery caused the Civil War. The movement quickly gained traction in the defeated South.