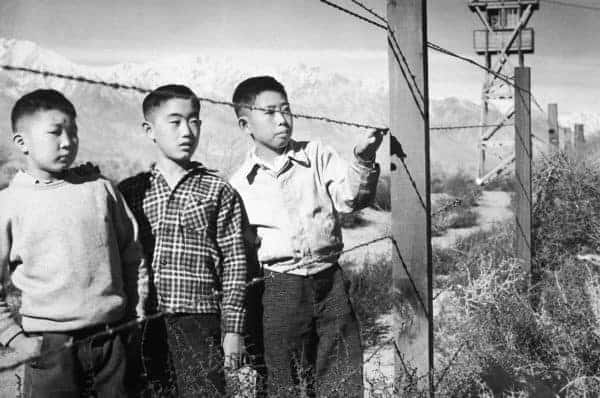

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the United States quickly learned that the war that raged in Europe could very easily make its way across the sea. Distrust and fear of those who had attacked the United States led to many people fearing those who looked like they might be from Japan.

President Roosevelt faced tremendous pressure to do something about the fear that was radiating throughout the west coast of the United States and therefore he set forth a policy that would deprive thousands of Americans of their rights. The internment of Japanese-Americans along with German and Italian Americans has become a dark spot in the country’s history as a time when the government overstepped its bounds and gave into fear.

President Roosevelt Even Imported Enemy Aliens From Latin America to Intern Them

President Roosevelt was not only concerned with Axis sympathizers in the United States but in Latin America as well. In July of 1940, he authorized the FBI to station agents at U.S. embassies throughout Latin America. Their goal was to have a list of names of people within those countries that they believed could have ties to axis powers. These agents were to keep an eye on those individuals and present the list should it become necessary to detain those individuals.

In many Latin American countries, after the outbreak of World War II, people who came from countries that were part of the axis powers became targets. Because those of Japanese descent stood out, they became easy targets. In May 1940, as many as 600 homes, schools and businesses belonging to citizens of Japanese descent were burned down. With the animosity toward those of Japanese descent in their countries it was little surprise that many Latin American countries were willing to comply with American requests to monitor and potentially detain those individuals.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the fear and hatred for people of Japanese descent only grew. President Roosevelt asked a dozen different Latin American countries to arrest citizens of Japanese descent. The idea was to detain all those individuals and then use them for hostage exchanges in order to get captured Americans back. Several countries complied and more than 2,000 people were deported from their countries and sent to internment camps in the United States.

Many of those who were deported to the U.S. were angry that they were forced to leave the lives they had built for themselves in their home counties. Families were broken apart and when mothers would take their children to try and find their husbands in the U.S. they would end up detained themselves. In the internment camps the focus was on teaching everyone Japanese, German or Italian so that when they were used in a hostage exchange or deported they could speak the language.