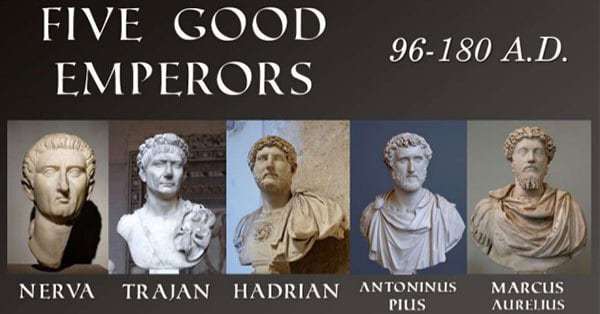

The history of the Roman Empire is littered with rulers that were cruel (Commodus), known for their bizarre proclivities (Elagabalus) or were utterly inept (Honorius). However, this great empire wouldn’t have lasted for centuries if the majority of its leaders were unsuited for the role. There were a number of excellent emperors, and for 84 years (96 – 180 AD), the empire thrived under the leadership of five outstanding rulers in succession. In this article, I will take a closer look at Rome’s 5 ‘Good’ Emperors.

1 – Nerva (96 -98 AD)

Domitian was the last of the Twelve Caesars, and most Romans were glad to see the back of him. Towards the end of his reign, Domitian treated the Senate with complete contempt and was considered a tyrant. In 96 AD, two praetorian prefects helped hatch a plot to eliminate the emperor, and on September 18, Domitian was murdered by two men; an ex-slave named Stephanus (who died in the bloody hand-to-hand struggle) and an unnamed man.

A well-respected lawyer named Nerva was chosen as the new emperor by the Senate, and it was a wise decision as he was the first in a line of outstanding leaders. It is a testament to his ability that Nerva is respected for his reign even though it only lasted two years. Nerva was forced to spend much of his time remedying the wrongs of his predecessor. He began by granting an amnesty to those exiled from Rome by the tyrant Domitian, and he even gave them their property back. Domitian’s network of informers was destroyed, and several of the spies were executed.

Although he apparently introduced a number of measures as a means of increasing his popularity, they were actually examples of good government in action. For example, he tried to relieve the poor by purchasing large lots of land from landlords and renting them out to Romans in need. Nerva also created a special fund for the purpose of educating children from poor families. His ‘good’ successors built upon this initial reform to improve education and care for the poorest members of society.

Nerva was the definition of a reluctant emperor and had the role thrust upon him. However, he was a sensible choice by the Senate given his political career. Nerva helped handle the Conspiracy of Piso and was given special honors by Nero. Vespasian chose him as consul in 71 AD, and Domitian followed suit by naming Nerva as a consular colleague in 90 AD. As he has the respect of practically everyone in Rome, the conspirators in the assassination of Domitian approached him. Nerva was allegedly on the cusp of being accused of treason by the increasingly paranoid tyrant, so he became involved to save his life, not to become emperor.

He was 65 years of age when he became emperor and was weak and frail with a tendency to overindulge in wine. While Domitian ruled with an iron hand, Nerva allowed everyone to do as they pleased. In 97 AD, there was a crisis in the military as it still held some semblance of loyalty to Domitian since he gave soldiers an overdue pay rise. They surrounded the emperor’s palace and demanded that he hand over the men involved in the death of Domitian. He refused but eventually, the two ringleaders were executed.

Nerva’s position was in jeopardy, and he knew he needed to do something to secure his position as emperor. He acted accordingly by choosing the governor of Upper Germany, Trajan, as his heir. Trajan was popular with the Senate, and the army and virtually everyone agreed that he was the ideal successor. Trajan was ‘adopted’ in October 97 AD, and Nerva’s authority was absolute. However, he did not get to enjoy it for long because he died on January 28, 98 AD. At the beginning of Nerva’s reign, the Senate referred to him as pater patriae, ‘father of the country.’ Although he was frail and feeble, Nerva began the process of an era of prosperity and nominating Trajan as his successor was a masterstroke.