Hurricane: a term likely derived from Spanish’s “huracan.” The Spanish word, in turn, shares roots with Caribbean tribal words for “Big Wind” and similar terms, e.g. “aracan,” “urican,” and “huiranvucan.”

Category Five Hurricane. Violent Typhoon. Very Intense Tropical Cyclone. Super Cyclonic Storm.

Humans differentiate the Earth’s most powerful storms with variable scales according to their location and strength, but each is synonymous with destruction. Following the advent of reliable meteorological records, weather planes, and satellites, contemporary scientists track and predict a storm’s course and strength with remarkable accuracy. Communities in the path of a dangerous storm receive ample warning time. Residents can reinforce their homes, and authorities can order evacuations.

Sure, numerous people choose to ignore the warnings or orders to evacuate, but that is a relatively new choice. Throughout most of human history, rough seas or approaching clouds was the only warning available to those unlucky enough to be caught in a furious storm’s path.

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey, Google is experiencing a surge of “most powerful hurricanes/storms/typhoons” searches. This list, however, is a collection of stories regarding hurricanes throughout sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Recorded observational data does not exist prior to 1492, and many of the following entries rely on European sources.

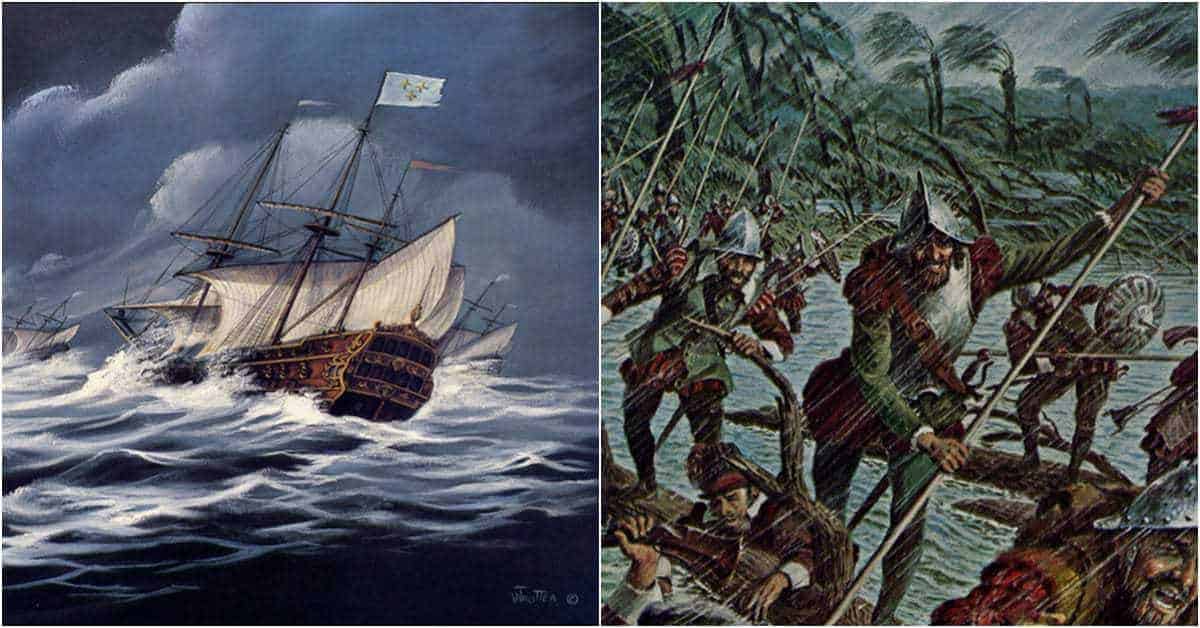

1494-1502: Christopher Columbus’ Hurricane Experiences

Christopher Columbus laid out the first European account of a hurricane in a letter to Queen Isabella in 1494, stating “nothing but the service of God and the extension of the monarchy should induce him to expose himself to such dangers.” The storm had made a strong impression on the explorer, and when he recognized the approach of a similar storm eight years later, the experience probably saved Columbus’ fleet. The same cannot be said for one of his rivals, Don Nicolas de Oravando.

Despite warnings to avoid Hispaniola, Columbus stopped at the port on June 29, 1502. He hoped to send missives to Spain and trade one of his ships. Shortly before his arrival, Columbus spied a storm that looked suspiciously familiar. He attempted to seek shelter on the southern side of Hispaniola in Santo Domingo. Don Nicolas de Oravando, the local governor, denied Columbus, and his fleet, access to the port, but permitted the explorer to send his letters and personal effects along with an outgoing “treasure fleet.” Columbus warned de Oravando of the storm’s approach, advised him to delay the treasure fleet’s departure, and promptly moved his ships to the island’s west side, interposing the land between his fleet and nature’s incoming fury. Orvando sent the ships anyway.

The hurricane crashed over Hispaniola on June 30, 1502. Wind and rain ripped Columbus’ ships from their anchors, but all of his fleet survived. The treasure fleet, however, had sailed directly into the storm, departing shortly before the hurricane’s arrival. Sources disagree on the size of the fleet, but at least twenty ships (possibly twenty-four or twenty-five) sank outright, either three or four returned to Hispaniola, and one ship successfully made it to Spain. Roughly five hundred of Orvando’s men died, but this was not the worst slap the disaster had in store for the governor.

Prior to Columbus’ departure from Spain, the King and Queen allowed him to appoint an accountant to tally his gold during his final voyage. Columbus chose Alonso Sanchez de Carvajal, an accountant and accomplished sea captain. Acting out of spite, Orvando assigned de Carvajal, and Columbus’ gold, missives, and personal effects, to the Aguja, the most pitiful ship in his fleet. Ironically, the Aguja was the ship that arrived in Spain safely.