Having the right hair, nails, makeup, and body shape- even the perfect teeth- sound like modern preoccupations. However, they were just as important to people in the past as they are today. While the desire to look good has not changed with time, fashion has- and so have the ways and means with which to achieve the look of the day.

Modern tastes and preoccupations can relate to some past beauty standards. Others, however, seem odd, alien or intriguing. Similarly, some old methods employed to change hair, skin and body shape are equally jaw-dropping. Some are stomach-churning, while others are downright deadly- demonstrating that in the past- just like today- some people would do anything for a ‘killer look.’

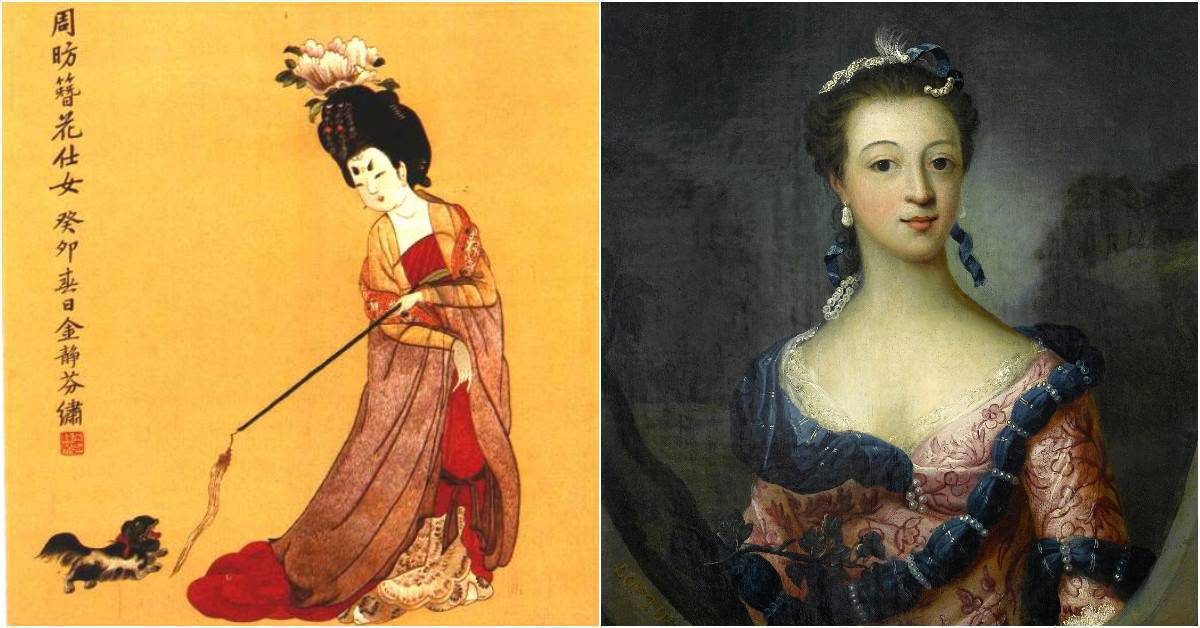

To illustrate the similarities and differences between the beauty standards of today and yesterday, here is a sample of some of the weird, wonderful and worrying fashions from the past- and the methods used to achieve them.

Forehead Plucking

During the Middle Ages, a lady’s face was not always her fortune. According to Victoria Sherrow in “For Appearance’s Sake: The Historical Encyclopedia of Good Looks,” breasts were more of a feature, while faces with a ‘ plain, empty appearance’ were desirable to persuade admirers to look lower down. An open, expansive face was partly achieved by scraping back the hair and hiding it under a hood or veil-which also conformed with the church’s moral policy. However, a high hairline was required to give a lady’s face maximum exposure. Not every woman had a naturally high forehead. So, to raise their beauty rating, Medieval ladies raised their hairlines artificially.

While the church may have wanted hair covered, they did not wish female members of their congregations to remove it wantonly for the sake of fashion. Priests who spotted signs of facial hair removal treated these ‘lascivious’ ladies to a lecture on the mortal sin of vanity. However, they grudgingly accepted the practice if the woman removed the hair “to remedy severe disfigurement or so as not to be looked down on by her husband.” Plucking the hairline did not fall into this category.

Ecclesiastical disapproval notwithstanding, the simplest and most common method was to pluck out the unwanted hair. Tweezers made of copper, bronze, and silver were all standard parts of the Medieval beauty kit. However, if a woman wanted to remove a lot of hair, plucking alone could prove to be a painful and arduous procedure. So, like today, ladies turned to depilatory creams.

Some of the preparations for hair removal were plant-based and seemed harmless enough. Parsley juice, Gum of Ivy, milk thistle steeped in oil and walnut oil were all believed to stop hair growth- especially if applied with pressure. Recommendations for application to the hairline included rubbing along the affected area or binding in place with a bandage while letting time and the concoction take their course.

Other preparations, however, are more unpalatable to modern tastes. Dr. Lemury’s Curiosa Arcana, published in 1711 preserves some ‘interesting’ suggestions for depilatory preparations. One recommendation was to grind eggshells and boil them in water to form a paste. The lady would then rub this into her hairline, presumably to exfoliate away the hair. This option was probably preferable to another favorite preparation Lemury records: cat’s dung in vinegar. For optimal results, Lemury recommended taking “hard, dry cats dung” and grinding it to a powder before mixing with vinegar and applying.