After the loss of the American colonies, Great Britain needed a new outlet for prisoners, many of which had formerly been sent to the Americas. It also needed land for Loyalists who were deprived of their property when the Revolutionary War was lost. In the Southwest Pacific Australia beckoned. The establishment of colonies in the lands claimed by Great Britain bolstered trade with the Indies, strengthened the British Empire at the expense of those of Spain and France, and offered a needed refuge for convicts. Several conflicts had already occurred between explorers and the indigenous people of Australia, but to His Majesty’s ministers, they were of no consequence. A transport fleet was assembled, and the colonization of New South Wales was begun.

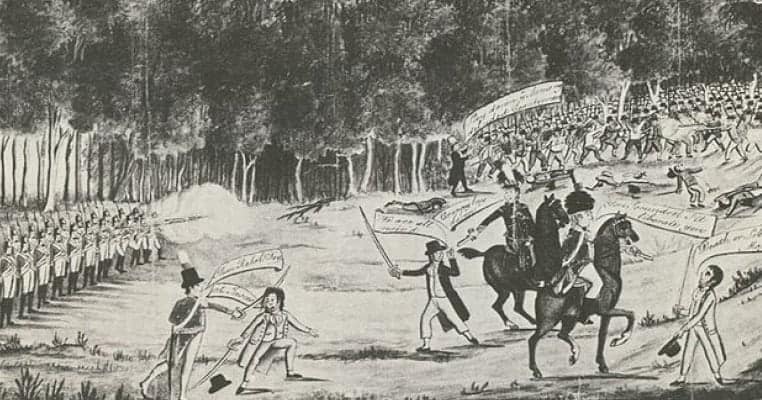

Born of a convict colony, and with resistant peoples standing in the way, Australia in the 19th century was foreordained to be a place of conflict. The settlement of Australia which began at Botany Bay was a time of hardship, frequent hunger, conflicts with the natives, and within the groups of settlers. For decades additional convicts were dispatched from Great Britain to the penal colony. They were often hardened urban criminals, adept at cutting purses, but lacking the skills needed for the colony to thrive. Gradually they were supplemented by free settlers. Some of the early prisoners gained their freedom, and the colony looked to expand, though the natives stood in opposition. Here is some of the history of the colonization of Australia in the 19th century.

1. An American Loyalist was the first to propose a colony in New South Wales

James Matra (he changed his surname to Magra for part of his life) was a New York-born resident of London when James Cook prepared for his exploration of New Holland in 1768. Matra joined the expedition, sailing with Cook in HMS Endeavor. His presence during the expedition led to a long friendship with the influential Sir Joseph Banks. Matra remained loyal to King George III when his countrymen rebelled against British rule, and in 1783 he wrote, A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales. His proposal was based on his observations during his voyage with Cook.

Matra envisioned the establishment of a British colony or colonies along the lines of the lost southern colonies, Virginia, Georgia, and the Carolinas. He suggested the Australian land and climate were suitable for crops to replace those lost. He also believed that he would make a fine Royal Governor for the colony, which was to be settled by American loyalists as compensation for lost lands. Convicts were included to fill the role of slave labor. His patron, Joseph Banks, opposed the idea of convict labor, suggesting that South Sea Islanders, familiar with the climate and the naturally occurring plants of the region, would make a more suitable labor force.