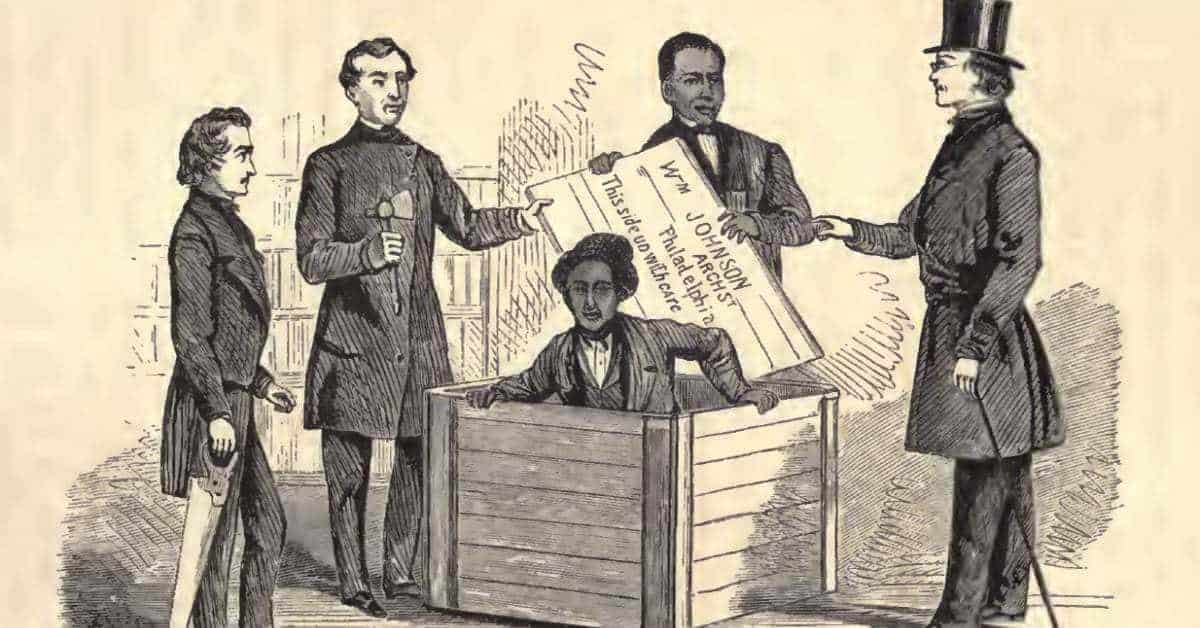

Given the nature of his remarkable escape, it is hardly a surprise to learn that Henry ‘Box’ Brown became a magician later in his life. Brown was a slave in Virginia until 1849 when he arranged to have himself mailed to Philadelphia abolitionists. He demonstrated his desire for freedom by remaining perfectly still inside the tiny crate on his incredible 27-hour journey. Brown received his obvious moniker after that and became one of the most important speakers for the Anti-Slavery Society. Read on to learn more about this remarkable man and his daring escape.

Early Years

Henry Brown was born into slavery in Virginia’s Louisa County in a plantation named Hermitage in 1815. He said his master was ‘uncommonly kind’ but also noted that the slave owner didn’t try to change the fact that the slaves viewed him as Almighty God and the young master was Jesus Christ.

Kindness or not, nothing got in the way of business. Brown was sent to Richmond in 1830 while his parents remained in Hermitage. He was brought to work in a tobacco manufactory owned by his master’s son in Richmond and Brown was living in the city at the time of Nat Turner’s Rebellion in 1831; the famous uprising took place in neighboring Southampton County.

According to Brown, slaves were “whipped, hung and cut down with swords in the streets.” He also noticed that the white residents of the region were “terrified beyond measure.” Brown pointed out that the revolt led to a new law being enacted; five slaves were forbidden to meet one another unless it was for work. During his time at Richmond, Brown had overseers that ranged from being decent men to those who were utterly sadistic in their treatment of the slaves.

Along with 120 other slaves and 30 free black employees, Brown had to work 14 hours a day in summer and 16 hours a day in winter. During his time in Richmond, Brown fell in love with a fellow slave named Nancy. They got married and had three children. Brown lamented the fact that his children suffered the same fate as him; they were born into slavery with no say in the matter and no rights. He was also fearful that the children would be sold; much like he was separated from his parents at a relatively young age.

Brown decided to try and keep his family intact by paying his wife’s master not to sell his family. However, he learned that the word of a slave owner was worthless and the cruel individual sold his three children and Nancy to another slaveholder in 1848. To make matters worse, Nancy was pregnant with her fourth child. Brown was forced to stand idly by as his wife and children formed part of a group of 350 slaves that marched by him in chains. Brown was disconsolate and spent several months mourning his loss. Finally, he resolved to break free from slavery and hatched an ingenious plot.