Few things inspire the popular imagination quite like the boy king of ancient Egypt, King Tutankhamun. He lived and reigned during the third millennium BCE, during a time of relative peace and prosperity for the desert oasis. His reign was remarkable in the fact that it was so unremarkable; in an era of constant warfare, Egypt experienced only a few battles with the neighboring Hittite Empire. It was also short, probably lasting for no more than a decade. But today, he is perhaps the most iconic figure of ancient Egypt, and people flock, in droves, to the North African country every year to see his tomb.

Today, he is probably more popular than he was while he was ruling as pharaoh! Many factors make him so well-known today including references to him in pop culture along with traveling exhibits of his burial chamber’s treasures and renewed interests in ancient Egypt. The hype began in 1922 when Howard Carter’s team of archaeologists discovered his tomb buried in the sand in the Valley of the Kings. Read on to learn more about the boy king, including his family, the poor health that plagued his reign, his death, and the alleged curse on his tomb.

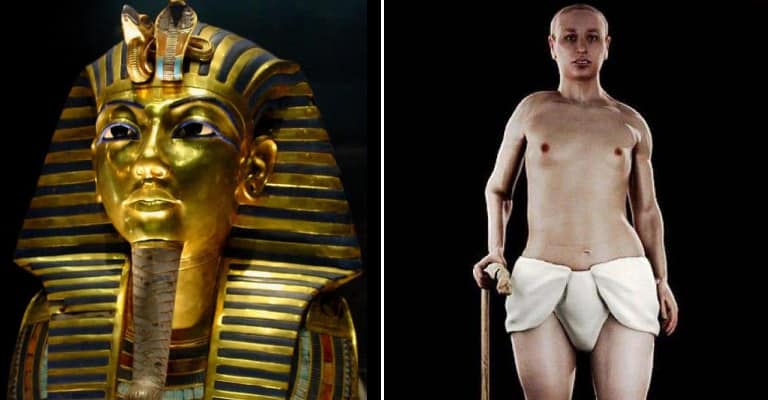

21. Background on King Tut

King Tutankhamun, who would become a pharaoh of ancient Egypt, was probably born on or about the year 1341 BCE. His father was Akhenaten, a powerful pharaoh who suspended the traditional polytheistic religion – which involved the worship of many gods and goddesses, such as Isis, Osiris, Horus, and many others – in favor of worshiping only the sun god, Aten. The name that King Tut’s parents gave to him at birth was actually Tutankhaten, which means “living image of Aten.” He changed his name to Tutankhamun, which means “living image of Amun.” Amun was another god in the Egyptian pantheon of gods and goddesses.

Akhenaten died in about 1334 BCE when Tut was only seven years old. Because he was too young to reign yet, two minor kings ruled in an interim period. He ascended to the throne in about 1332 BCE, when he was probably only nine or ten years old. As Tutankhamun, the image of Amun, one of the most significant accomplishments of his reign was the restoration of the worship of Amun and the traditional pantheon rather than the monotheistic worship of Aten. Though he only reigned for about nine or ten years, historians have found that the short reign of the boy pharaoh was markedly important in Egyptian history.