Based on a collection of fantasy short stories and novels by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski, The Witcher is a fantasy series that has since developed into a global franchise. Encompassing most prominently the critically acclaimed video games series, in 2019 the beloved world will be brought to life by Netflix on television.

An immensely detailed and rich world rivaling the greats of the genre, Sapkowski’s fictional universe includes an array of ferocious and terrifying monsters. Drawing inspiration from his own cultural roots, much of Sapkowski’s creation is borrowed from traditional Slavic and European folklore and refashioned for modern audiences unfamiliar with the less child-friendly stories of yesteryear.

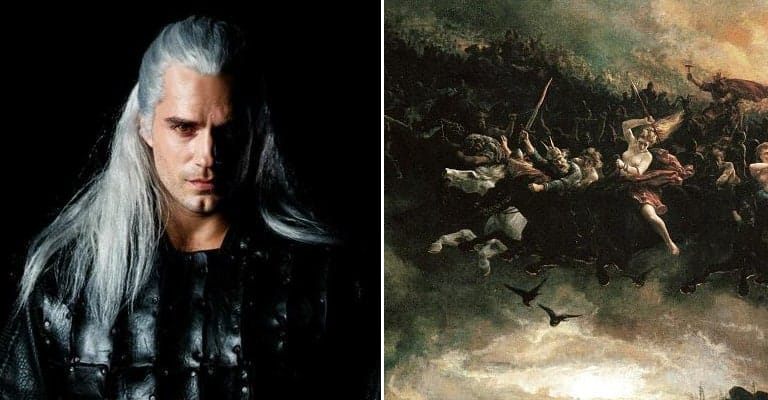

Here are 16 times The Witcher borrowed from real-world mythology:

16. The “Trail of Treats” found in The Witcher 3, serving to guide children to the witches of the forest, is a clear homage to the famous German fairy tale Hansel and Gretel

In the course of The Witcher 3, Geralt is forced to enter Crookback Bog in search of the Bloody Baron’s lost wife. Signposting his route through the bog to the crones supposedly residing within the claustrophobic swamp, sweets and candy litter the path and even appear to grow from the trees themselves. Serving to guide orphans seeking the “Good Ladies”, many parents of the surrounding villages, suffering from too many mouths to feed, abandon children in the bog believing their offspring will “never want for anything again, for the Ladies are kind and generous”.

A clear homage to the German fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, recorded by the Brothers Grimm and first published in 1812, whereupon the young children are led into the forest by their father and subsequently abandoned. Initially leaving a trail of pebbles to find their way home, the following day the parents return them to the forest once more. This time, Hansel’s efforts to leave a trail are immediately thwarted, for having used breadcrumbs the siblings discover their tracks were eaten by birds. Arriving at a gingerbread house, in more modern versions located by following a trail of sweet wrappers, the children find a bloodthirsty witch disguised as a kindly woman.