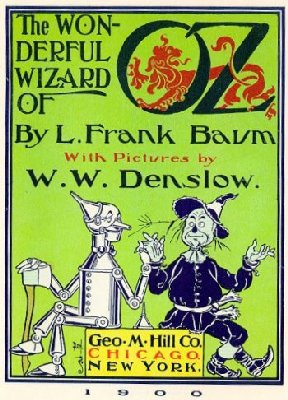

“The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”, written in 1900 by L. Frank Baum and followed by the iconic cinematic masterpiece starring Judy Garland in 1939, has remained one of the most enduring and popular stories over a hundred years later. Exploring serious themes such as courage, humanity, and evil in an open fashion accessible to children and adults alike, the story equally contains numerous hidden messages and meanings, many of which were not discovered until decades after publication, with scholar Quentin Taylor concluding “Oz operates on two levels, one literal and puerile, the other symbolic and political. Its capacity to fascinate on both levels testifies to its remarkable author’s wit and ingenuity.”

Here are 16 hidden symbols and messages that you might never have noticed before in L. Frank Baum’s “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”:

1. The lead character, Dorothy Gale, symbolizes the average American

Dorothy Gale, the lead character of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, is an 11-year-old orphan girl who resides in Kansas with her Aunt Em and Uncle Henry. Allegedly influenced by the immense popularity of Alice in Lewis Carroll’s works, Baum structured his own story around a similarly sympathetic and identifiable protagonist. Multiple theories exist regarding the naming of the character, with some claiming the role was so named in memory of a victim of a tornado in Irving, Kansas, in May 1879 whilst others assert Dorothy was named after Baum’s own niece who died in infancy and whom his wife Maud grieved extensively for.

Less known is that Dorothy symbolically represents the average American, and arguably serves as an allegory for the United States itself. Described as “each of us at our best – kind but self-respecting, guileless but levelheaded, wholesome but plucky”, Dorothy figuratively speaking stands for the average American stoically looking for a solution to their worldly problems. In “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” Dorothy is characterized by a level of independence beyond her years, as an incessant optimist in the face of uncertainty, and through her own assertiveness the leader of her group in spite of her young age. Each of these traits, upon closer inspection, resembles a defining trait of the United States: a young nation which won independence from an older force and who idealistically believes in opportunity and a better future for herself and others.