We’ve all been lost at one time or another. Some people find it easy to get lost in a new place, perhaps on holiday or when moving to a new area, yet still others just have a natural inclination to lose their way, however familiar the terrain, and resort to Google Maps. But we all have one acquaintance upon whom we can rely for navigation, and it is probably not too great a generalisation to make about the human race to say that there are two types of people: those who can find their way, and those who cannot.

Unfortunately, many people do not realise that they fall in the latter camp, and history tells us that ignorance of one’s navigational impotence is an age-old condition from which many individuals (and their followers) have suffered. But it is one thing to be unaware of how useless you are at finding your way whilst rarely straying far from home, and another to base your entire career on the insubstantial foundation of your poor sense of direction. Countless people throughout history have made just this myopic error and become professional explorers, with results inevitably ranging from the comic to the fatal.

But there are many kinds of useless explorers and dreadful expeditions. Some of history’s most famous explorers have made grave navigational errors resulting in fantastic discoveries for which they are praised. Others have mismanaged the practicalities of exploration, with disastrous consequences. But what is apparent through all is the bravery of the explorers, however brutal their crimes or inept their attempts to discover new places and things, and this initial impulse is laudable when divorced from the outcome. But let’s not let that stop us having a chuckle at some of the following self-confident buffoons and their disastrous enterprises.

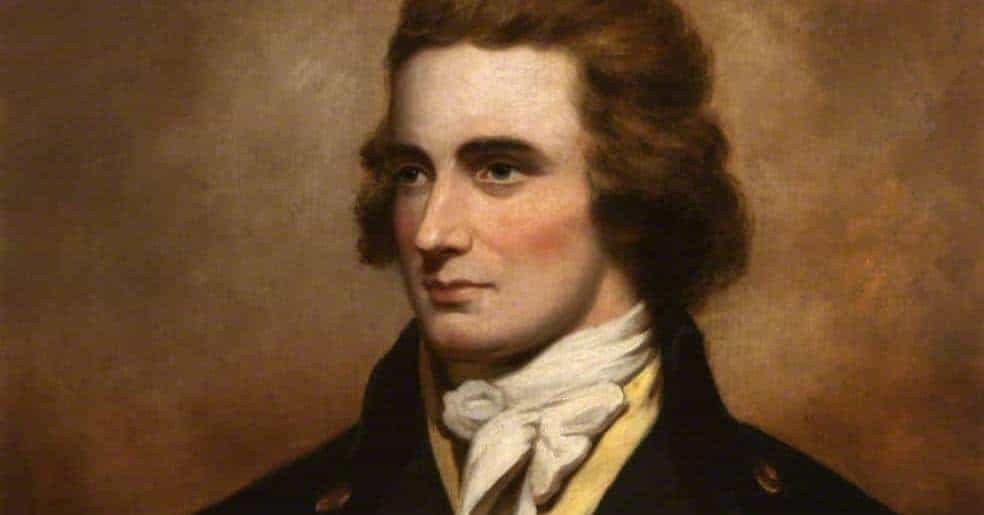

Christopher Columbus

The man remembered for being the first to discover America may seem a strange place to start on a list of inept explorers and failed expeditions, but Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World was the result of some seriously poor navigation. When ‘in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue’, as the old rhyme goes, he was actually aiming to find a new route to Asia. Landing instead in what is now known as the Bahamas, Columbus assumed he had arrived in Asia, and so called the area ‘the West Indies’, as opposed to the East Indies, or Asia.

Columbus (1451-1506) was born in Genoa, on the coast of Italy. His father was a wool-weaver and cheese-seller, and so it seems most likely that Columbus’s wanderlust came from his encounters with the sailors who frequented the Genoese ports. Weaving and cheese-selling do not seem to have appealed to young Christopher, and so he worked as a business agent for some of the most prominent Genoese families, a job that involved him travelling the world by sea. One of these trips took him to Lisbon, where his younger brother, Bartolomeo, who also became an explorer, worked in a cartographer’s shop.

His experience of global trading led Columbus to consider whether there could be a better way to trade with the Far East than taking the Silk Road or the Cape Route. Based on his calculations and research, Columbus proposed sailing west to reach Asia. Famously, his proposal was rejected by the Portuguese, English, and French monarchs, as well as Venice and his native Genoa. Eventually, Columbus gained financial backing for his voyage from King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. Though his calculations were incorrect, and Columbus failed spectacularly to reach Asia, he succeeded in reaching the Americas.

A prominent myth about Columbus’s voyage was that he was the first man to discover America. He wasn’t – a party of Vikings led by Leif Erikson reached North America in around 1000, naming it Vinland, but returned to Iceland after the natives proved too hostile. This is also to say nothing of the indigenous populations living in North and South America, who first ‘discovered’ America around 14, 000 years ago. It is also a myth that no one would sponsor Columbus because they believed the world was flat – people had known the world was spherical since Aristotle’s time.

It would also be remiss not to mention Columbus’s heinous crimes as 1st Governor of the Indies. Modern historians have pointed to him enslaving natives and forcing them to convert to Catholicism as reasons not to look kindly upon the Italian. For example, he once kidnapped a native woman and gave her to a crew member to rape, and on Hispaniola he once cut off the ears off a native to scare others into complying. Most startlingly, when he arrived on Hispaniola the island’s population was 300, 000. 56 years later, only 500 remained, due to mass suicides and persecution.