Loyalty, duty, honor, and keeping faith with one’s side through thick and thin are prized military values, counted among the bare-bones basics expected of soldiers. If soldiers lacked such minimal expectations of their comrades marching and fighting at their side, and perhaps even more importantly, of their leaders and chain of command, morale would quickly crater and collapse in military units, and armies would succumb to a loss of cohesion, confidence, and discipline. That would transform armies from well oiled and well run fighting machines, and into brittle potential mobs, susceptible to shattering into panicked rout at the earliest difficulty.

Yet, many a general over the course of recorded history treated loyalty and keeping the faith with one’s side as if the concepts were used toilet paper, and discarded them in order to switch sides and defect to the enemy. For a variety of reasons – be they base and straightforwardly venal such as bribes and financial reward, resentment at treatment received from their employers, or some higher ideals – many a military leader over the millennia ended up turning coat and fighting against his side. Sometimes against the very soldiers whom he had led not long ago. While some reaped the just rewards of treason, others profited handsomely from their betrayals and went on to live happily ever after, or as close to that as one can come in real life.

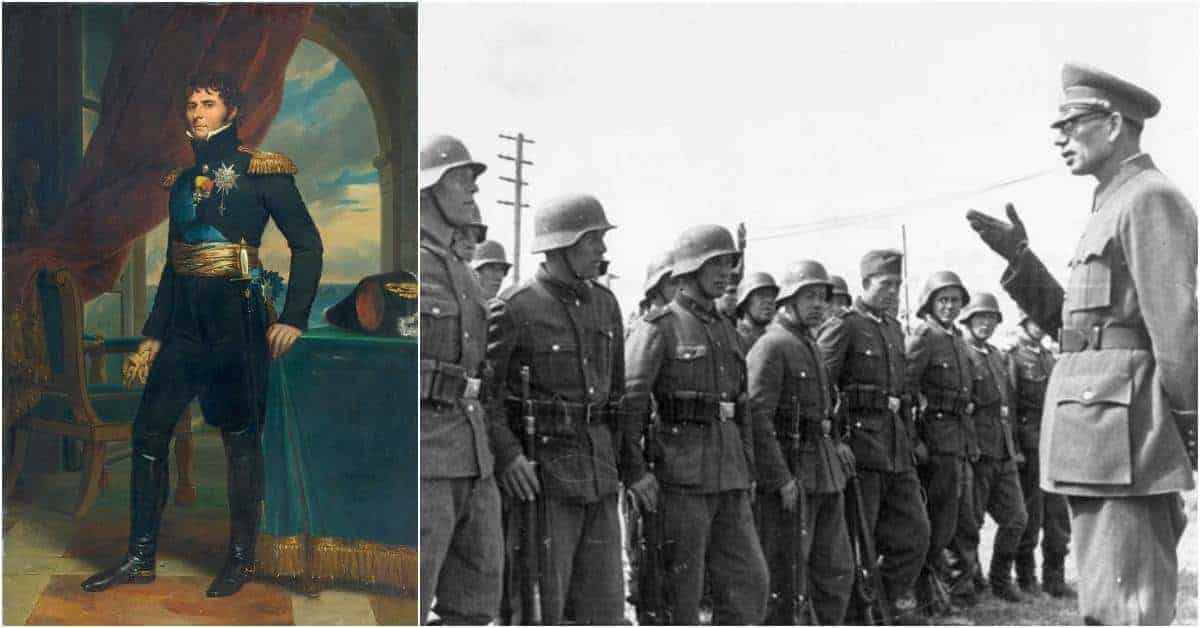

Following are 12 generals who switched sides and turned coat, from ancient through modern times.

Phanes of Halicaranassus

Phanes of Halicarnassus (flourished 6th century BC) was a respected Greek mercenary general who served Egyptian Pharaoh Amasis II (570 – 524 BC). During a war between Egypt and Persia, Phanes switched sides, and joined the forces of Persian king Cambyses II in his invasion of Egypt, helping him defeat and conquer Phanes’ former employers and paymasters.

The war reportedly started because an Egyptian doctor in the Persian court was angry at Pharaoh Amasis for choosing him out of all of Egypt’s physicians, to drag away from his family and send to distant Persia when Cambyses wrote Amasis asking for an eye doctor. The doctor got his revenge by advising the Persian king to ask for Amasis’ favorite daughter, knowing that it would put Amasis in a bind: accept and grow wretched at the loss of his daughter, or refuse, and offend Cambyses.

Amasis, not wishing to send his beloved daughter to Persia, knowing that Cambyses intended her for a mere concubine, but also intimidated by Persia’s power, sent the daughter of a former Pharaoh, claiming she was Amasis’ own. Soon as she reached Persia, however, the former princess told Cambyses of the ruse. Angered, he declared war and prepared to invade Egypt.

As Amasis gathered his forces and prepared Egypt’s defenses, he managed to offend Phanes, and the disgruntled Greek general switched sides and set out to join Cambyses. Amasis sent assassins to kill or capture him, but after harrowing adventures, including an escape from captivity by getting his guards drunk, Phanes managed to reach Cambyses.

The Persian king was trying to figure out the best invasion route into Egypt, and Phanes recommended a route through Arab tribal lands. He advised Cambyses to seek safe passage from their rulers and to sweeten the request with generous gifts. The Persian king heeded Phanes’ advice, and the Arabs gladly granted safe conduct through their territory.

By then, Amasis had died and was succeeded as pharaoh by his son, Psamtik III who, enraged at Phanes, tricked the Greek general’s sons into meeting with him, took them captive, and had them executed. Then, as an object lesson to would-be traitors, he had their blood drained and mixed with wine, which he drank and made his councilors consume as well.

Phanes got his revenge by leading the Persian army into Egypt, acting as Cambyses’ guide and military advisor. With the Greek general’s assistance, the Persians defeated Psamtik’s forces, forced him to retreat to his capital, where they besieged and eventually captured him. Phanes then engineered the execution of his sons’ murderer by uncovering and informing Cambyses of a plot by the captive pharaoh to stir up a revolt.