Gandhi is one of the titans of the international peace movement, with a name that ranks alongside all of the great purveyors of the humanist message, from Mother Teresa to Nelson Mandela. Gandhi was many things to many people, although he has tended to be associated primarily with the Indian independence movement – and in fact, the opening paragraph of his Wikipedia page describes him as ‘an Indian activist who was the leader of the Indian independence movement against British rule.’

This proves that even Wikipedia can over, or under emphasize the facts. Gandhi was just one member of the Indian independence movement, and not by any means its leader, and he certainly was never in line to assume leadership of the independent nation of India. Gandhi was a man of the people, an a national and spiritual leader, and one of the great, global ambassadors of peace. His message was universal, transcending all national boundaries

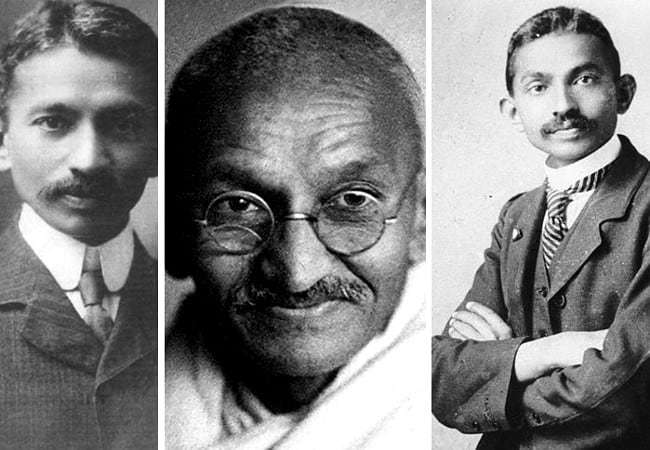

In this list we will dig up a few interesting facts about the great man, burst a few myths and hopefully make a few revelations. Just by way of essential background, however, Gandhi was born in in 1868 in the principality of Porbandar, now located in the modern Indian state of Gujarat, and he died in 1948 at the age of seventy-nine. He is buried in a memorial garden on the banks of the Yamuna River of the eastern outskirts of New Delhi.

Gandhi’s name was not ‘Mahatma’

It is probably one of the most enduring myths surrounding the Gandhi name, that ‘Mahatma’ was his first name, which it was not. Gandhi’s birth name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, and the name ‘Mahatma’ was added only later as an honorific, as he began to develop his reputation as a great spiritual leader. The standard dictionary definition of ‘Mahatma’ is ‘a person regarded with reverence or loving respect; a holy person or sage’, or ‘a person in India or Tibet said to have supernatural powers.’ Most devotees of Gandhi, however, will answer that question with the reply that ‘Mahatma’ means simply ‘Great Soul’, derived from the Sanskrit महा (maha) meaning ‘great’ and आत्मन् (atman) meaning ‘soul, spirit, life.’

Gandhi certainly began his life as a political activist and organizer, but very quickly his spiritual identity began to eclipse his activism, at which point he began to evolve a style of religious-inspired activism and political awareness around his essential belief and adherence to Hinduism. He was, however, polytheistic insofar as he did not credit Hinduism ( which is itself a polytheistic faith) with sole access to the ‘truth’, but he was prepared to acknowledge every branch of faith, and preached the ideal that adherence to a specific faith was less important than simply having a spiritual identity. That a man or woman worships according to his or her own style satisfied him, as long as that worship was authentic and committed.

There are numerous theories on when Gandhi began to be known as Mahatma, but it is now generally accepted that the title was first publicly employed in 1915 by the great Indian polymath Rabindranath Tagore, introducing Gandhi by this honorific to a gathered audience. It is also probable that the name had entered circulation already, probably among the devout peasants who comprised Gandhi’s most loyal following.

However it happened, Mohandas K Gandhi is now most commonly acknowledged as ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi, in respect of the fact that, above all else, he was a spiritual leader.