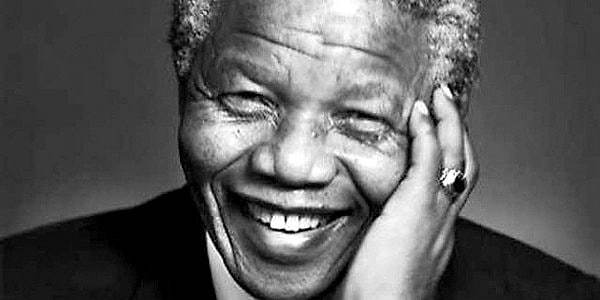

Of all the great social icons of the 20th century, Nelson Mandela probably tops the list. He is right up there with Gandhi and Martin Luther King, and probably, for the scope of his influence and achievements, he stands rather higher. He was born in 1918, the year that WWI ended, a moment that marked the beginning of the age of African liberation.

By 1918, almost every scrap of Africa lay under the sovereignty of one or other of the European powers. The War, however, shook the foundation of global empire, and it certainly served notice on those empires that survived – namely the British, the French and the Portuguese – that the end was nigh. At about this time, the first generation of university educated backs were beginning to filter back into their respective colonies, and it was they who commenced the early organization of black political resistance.

It would take another war, however, for the movement to solidify. If WWI weakened the British Empire at the knees, it was WWII that put it on the canvas. Hundreds of thousands of demobilized black troops flooded back to their colonies, disgruntled at the lack of their own freedom, and in combination with the new black intelligentsia, founded the first mass movements of liberation. Prominent in the South African movement at this time, of course, was a young black attorney by the name of Nelson Mandela.

Nelson Mandela’s first name was not Nelson

Nelson Mandela was born in a region of South Africa known as the Eastern Cape, and he belonged to a language group known as the Xhosa. This is perhaps best pronounced by a non-Xhosa speaker as core-sa, because there are very few people who are not indigenous South Africans who can bend their tongues around the phonetic clicks that characterize southern African Bantu languages.

The Xhosa are part of a wider language group known as the Nguni, which also includes the Zulu, and traditionally they have tended to be the most politically alert of South Africa’s many tribal subgroups. The Eastern Cape was the birthplace of the African nationalist movement in South Africa, and Mandela was born into a vibrant black political culture, at a time when the worst oppression of apartheid had yet to be felt.

The forename that he was given at birth was Rolihlahla, another name almost impossible for a non-South African to pronounce. Whoever decided on that name, however, certainly sensed something unusual about the child, for it’s idiomatic translation means something along the lines of ‘troublemaker’. In later years, he was probably better known by his clan name, Madiba, but the question is, where did the ‘Nelson’ part come from?

Well, in the early decades of the twentieth century, black South African youth were typically educated by Wesleyan or Methodist missionaries, and the price paid for that education was often an obligation to convert to Christianity, to abandon traditional worship and to adopt western dress, lifestyles and habits. Part of the de-Africanization effort was to give young students western names in place of their traditional names, and Mandela’s teacher chose rather randomly the name ‘Nelson’. This practice was usually accepted, but used only in regards to a person’s interactions outside of the traditional sphere. The name, however, became part of his official identification, and the rest, as they say, is history.