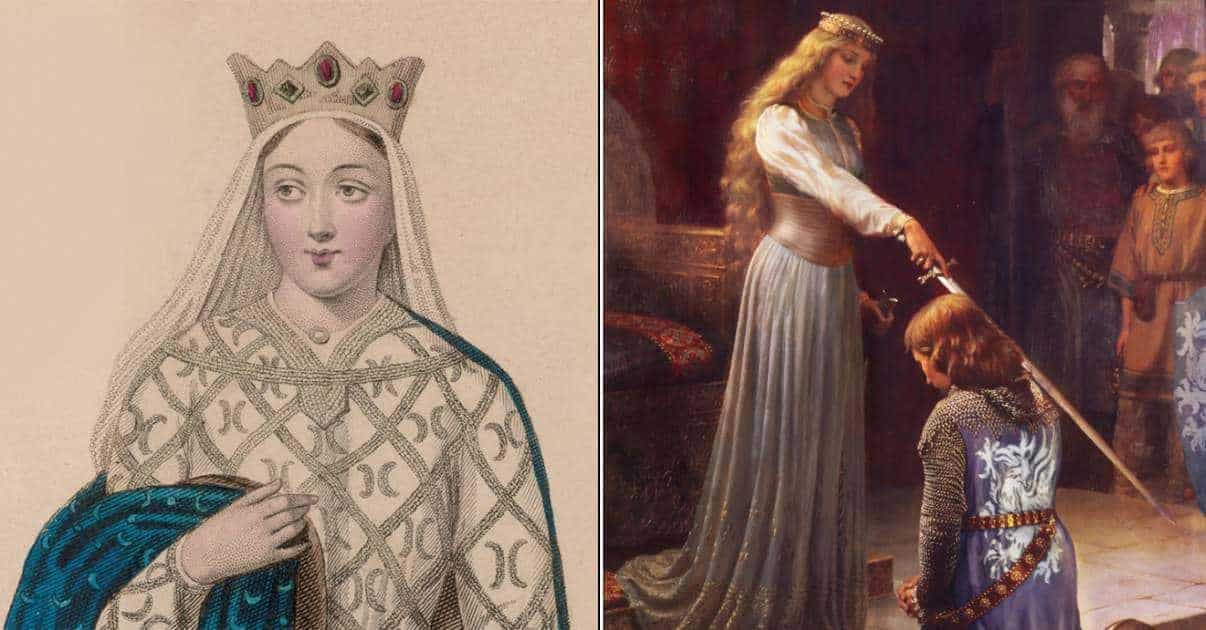

Eleanor of Aquitaine was one of the most captivating figures of the medieval period. In a time when women were meant to be seen and not heard, Eleanor of Aquitaine became one of the most famous – or infamous – women in Europe. What we know about much of Eleanor of Aquitaine has been painted in legend, yet her life was scandalous for a medieval woman. She became a Crusader; she committed treason; she spent sixteen years in prison; she started a rebellion, and she stopped one.

Even though she was a duchess in her own right, her first husband’s advisors and her second husband’s controlling nature limited her power. She struggled against these boundaries to become one of the most influential women of the Middle Ages. Her volatile second marriage to Henry II created the Angevin Empire, which comprised of most of the British Isles and half of modern-day France. Their descendants are some of the most famous Plantagenet kings of the medieval period, such as Richard the Lionheart, King John, and Edward I, the Hammer of the Scots.

She Was Born Because of a Scandalous Love Affair

Eleanor was raised in the Aquitaine court where courtly love was the norm and men and woman conducted affairs in the open, even her own grandparents. Her grandfather, Duke William IX of Aquitaine was married to Philippa of Toulouse, but he took Dangereuse, the wife of one of his vassals, as his official mistress, and they weren’t shy about their love affair.

Duke William IX shamelessly flaunted his mistress, and he even brought her to live with him in his castle, a move that got him in trouble with the Church. William was excommunicated for his affair, but he cemented it by threatening the lives of the bishops who enforced his excommunication. Dangereuse was William’s mistress for the rest of their lives, but William IX wasn’t known for his fidelity. To keep her position, Dangereuse made sure to tie herself permanently to the royal family: she married her daughter Aenor to William’s son, the future William X of Aquitaine. William and Aenor had three children: a son who died young and two daughters, Petronilla and Eleanor of Aquitaine.