The French Revolution of 1789 had a greater political, intellectual, and cultural impact, than any other revolution in history. It inaugurated a worldwide shift from the absolutist monarchies that had governed most of mankind for nearly all of recorded history, to democracies, republics, and modern states. With the possible exception of the US, the 1789 Revolution’s principles defined the terms of political debate, whether pro or anti French Revolutionary concepts, for nearly all political movements ever since.

The French Revolutionary regime disintegrated into chaos within a few years, and the Revolution was hijacked by Napoleon. However, Napoleon was a creature of the Revolution. He cemented its core results in his Napoleonic Code, and spread its principles wherever his soldiers marched. Just about every revolution and progressive movement in the world after 1789 drew from the French Revolution. Liberalism, secularism, nationalism, radicalism, socialism, feminism: all derive from the French Revolution. Social democracy? Traces back to the French Revolution. Socialism? Likewise. British liberalism? An attempt to avert a French style revolution in Britain. Communism? Extremist neo Montagnards. Fascism? That is simply Egalite + Nationalism + anti communism.

Even today’s non secular or anti secular ideologies, such as political Islam, emerged as a reaction to the spread of the French Revolution’s political concepts. Al Qaeda, ISIS, and all religious extremist movements around the world today are, at core, a violent backlash against the world shaped by the 1789 upheaval. Today, just about all of us live in a world shaped by or in reaction to the French Revolution, and most of the world’s population lives under systems of law derived from or modeled upon the Code Napoleon. That is a long and long lasting shadow cast by a single revolution.

Following are ten ways, big and small, that the French Revolution impacted and shaped the modern world.

The End of Feudalism and the Divine Right of Kings

Most people today are accustomed to egalitarianism and equal treatment before the law as basic concepts of governance and social organization. Even where such concepts are not actually practiced, they are at least given lip service. Before 1789, however, the majority of mankind lived in highly stratified societies with stark class divides, in which differing treatments under the law based on class were routine. In such societies, a small and parasitic aristocratic elite lorded it over a mass of exploited and oppressed commoners. And heading the aristocracy was a monarch, claiming a divine right to rule and exploit all.

Most commoners in such societies were peasants, tied to the land and toiling in conditions of peonage and serfdom. The remainder were otherwise engaged in trades or other service sector employments for the ultimate benefit of an aristocracy. The aristocrats seldom bothered to conceal their contempt for the commoners, particularly the peasants, whose very occupation’s name was often used as a pejorative.

Social custom and religion, with its promise of a better life in a world to come, did much to reconcile the commoners to their lowly lot in this world. However, custom and religion sometimes failed to keep the commoners content, and they rose to demand a fairer redistribution of the pie. When that happened, the aristocrats were often successful in using their monopoly of government to maintain their grip on power. Especially via their access to organized and disciplined military forces, which they unleashed on the commoners to cow and keep them in line.

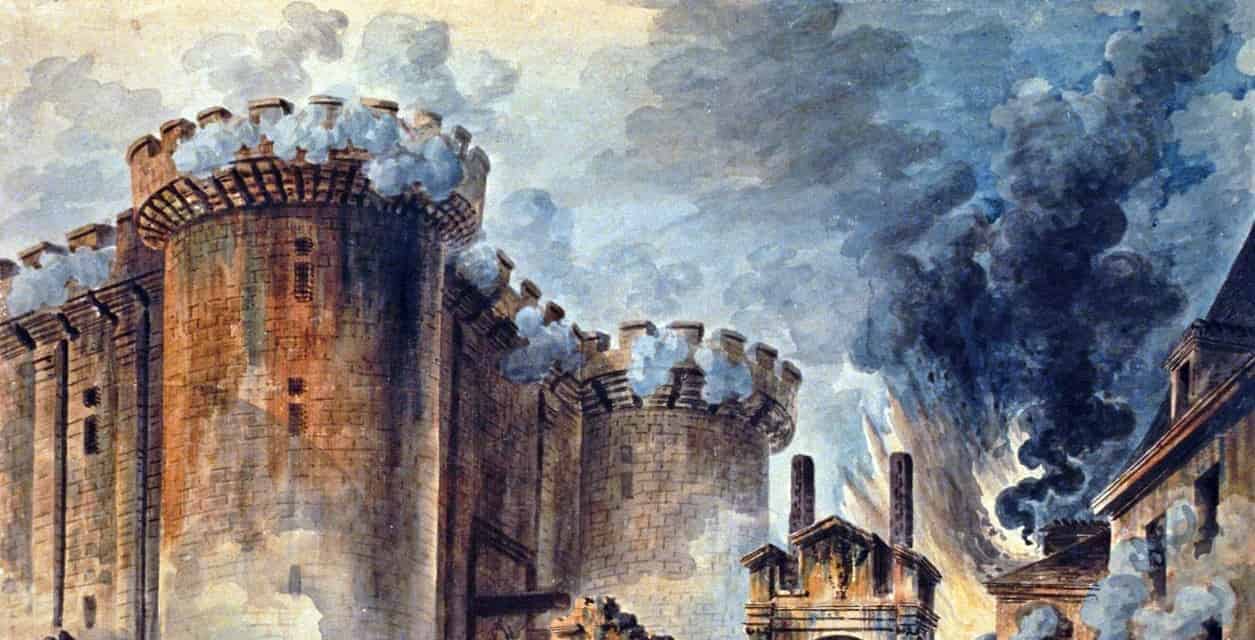

Until 1789, France and most of Europe were such societies. The French Revolution would upend the system that had allowed such societies to exist for millennia. In 1789, forces were unleashed that would eventually consign government by aristocrats and absolute monarchs claiming a divine right to rule, to the dustbin of history. One of the French Revolution’s first steps was to abolish absolutist monarchy, and replace it with a constitutional one accountable to the nation, before getting rid of monarchy altogether. Simultaneously, all aristocratic privileges were abolished.

France’s Revolutionary armies would spread that hostility to absolutist monarchy and aristocratic privilege throughout Europe. Once that genie had left the bottle, there was no putting it back, neither in France nor in the rest of Europe. Even after the French monarchy was restored following the defeat of Napoleon, it was restored as a constitutional monarchy, not an absolutist one like in pre-1789 days. In the rest of Europe, the decades after Waterloo were marked by a conservative backlash against the French Revolution’s ideals. However, even amidst such backlash, the clock was not wound back completely to pre-1789 days. The ensuing 19th century was marked by a gradual shift towards increased liberalism and constitutionalism, while the power of monarchs and aristocrats steadily declined.