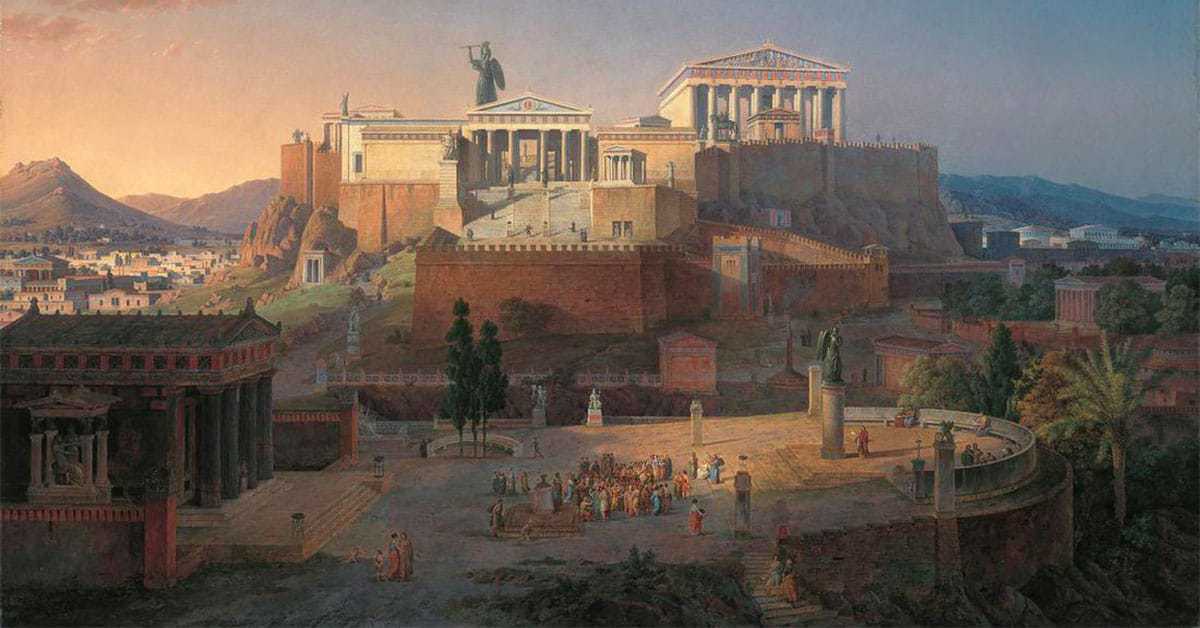

Ancient Athens is often referred to as “The Cradle of Western Civilization” because of the impact and influence of its political and cultural achievements, particularly during the Classical period (508 – 322 BC), on subsequent European development. Following are ten prominent figures from Ancient Athens.

Solon

Solon (630-560 BC), nicknamed “The Lawgiver“, established the foundations of the subsequent Athenian democracy. He is credited with reforms that ended the aristocracy’s exclusive control of government, replacing a political system controlled by a blood nobility with an oligarchy controlled by the wealthy, regardless of pedigree. For millennia, wealth had been based on land ownership, which ownership was disproportionately concentrated in the hands of a hereditary aristocracy. As in the rest of Greece, Athens was dominated by nobles who owned the best land and monopolized government.

The Athenian region of Attica was made of three parts: The Plains, a prosperous agricultural interior; The Coast, which relied on fishing and trade; and The Hills, an impoverished region containing a majority of the population, mostly shepherds and small farmers scratching a living from poor soil. Over the centuries, a pattern had developed in which poor farmers borrowed seed from rich aristocrats to plant, then repaid the loan at harvest time with grain and labor.

That pattern was disrupted in the 7th century BC when commerce revived after a centuries-long slump, and the non-aristocratic Athenians of the coast got into seaborne trade, bought land with their profits, and, using slave labor, farmed it more efficiently than the aristocrats. The aristocrats, finding themselves outcompeted by the nouveau riche, resorted to squeezing their poorer neighbors, enslaving them and seizing their farms whenever they failed to repay their seed loans on time.

That outraged other Athenians – not that they objected to slavery per se, but to the enslavement of Athenians. That, combined with the resentment of the middling farmers, craftsmen, and rising merchants at their exclusion from government, brought Athens to the brink of revolution. So the citizen body met in the Ecclesia, the Athenian Assembly, and entrusted Solon, a respected aristocrat, to reform Athens, binding themselves with solemn oaths to accept his decisions.

Solon’s reforms solved the immediate problem, even as they upset all sides. The wealthy were upset because he canceled debts, freed the Athenian debt slaves, and prohibited the future enslavement of Athenians. The aristocrats were upset because he granted the vote to all adult male citizens, regardless of class or wealth. The poor were upset because he did not return the lands that had been seized by the aristocrats, refused to break up the big estates and redistribute the land, and because he reserved all posts in the Athenian government for the wealthy. And the wealthy were split because some government positions were reserved for aristocrats, to the exclusion of non-nobles.

Despite the discontent, the Athenians kept their promise to accept Solon’s decision. That done, and in order to avoid having to constantly defend and explain the reforms, Solon left the Athenians to work out the kinks in his new system, and went traveling, informing his fellow citizens that he would be gone for at least ten years.

Solon’s reforms alleviated the immediate crisis and averted civil war, but they did not resolve many underlying tensions that would continue to plague Athens for years. Solon took the first steps by making all citizens equal before the law and reducing the power of the aristocracy, but it would take generations of reformers to build upon and fine tune what he had created before Athenian democracy was established.