It was the first war fought by the United States against a foreign power, a projection of national strength and determination against enemies overseas. The transgressions of the Barbary States, Morocco, Tripoli, and Algiers against American shipping, intolerable and costly, led to the creation of the United States Navy and Marine Corps. The United States of America’s first great heroes were the young officers who led its ships to victory on the shores of Tripoli. The United States established a naval presence in the Mediterranean which has been maintained ever since, ensuring safe passage for its merchant ships as well as those of other nations.

American ships had been protected from the Barbary pirates by the Royal Navy until independence was achieved, after which its ships were seized by the pirates and their crews held hostage or sold into slavery. The only defense was the payment of tribute, which became so expensive – nearly 20% of the national budget – that Americans decided the building of a navy was a better investment. The navy’s performance during the Barbary wars made it a source of national pride, as the United States fought what was, in essence, its first war against Islamic (then called Mohammedan) terrorists.

Here are some of the events of the wars against the Barbary pirates and the birth of the United States Navy.

The Barbary Pirates

For two centuries, Ottoman and Berber raiders from the ports of North Africa, Algiers, Tangier, Rabat, Tripoli, and others, raided throughout the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic. The coast of western Africa, the ports of Spain and Portugal, and the British Channel were subject to their raids, which were based on the desire to capture Christian slaves for sale within the Muslim lands. The seizure of the precious cargoes of the merchant ships they preyed upon was secondary, though it made many local chieftains in the Barbary States wealthy. The raiders also preyed upon each other, both at sea and on land in North Africa.

By the late eighteenth century, the powerful navies of the French, Spanish, British, and Dutch had mostly suppressed their raids in the Atlantic, though they continued in the Mediterranean and around Gibraltar, hit and run raids which expanded as the Europeans were distracted by warring with each other. Ships of neutral nations, including those of the United States, were easy targets. To avoid the capture of ships, the various rulers of the Barbary States, which were vassals of the Ottoman Empire, demanded annual payments of tribute. It was common practice for the ruler of a given state to accept the tribute and then look the other way as ships left his ports to violate the agreement.

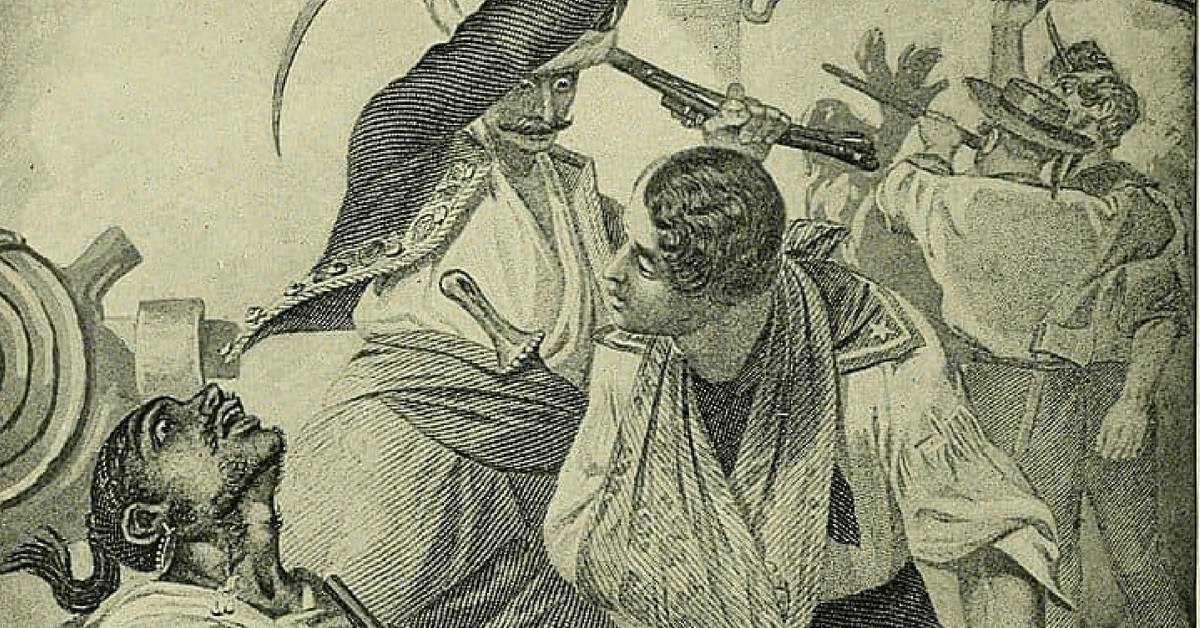

For the most part the Barbary States did not kill the crews of the ships they seized as the sailors and passengers were too valuable as slaves, and in the case of female prisoners, as concubines. Prisoners could be ransomed, on the whim of the individual holding the prisoner, and often emissaries sent to negotiate the release of a prisoner were simply imprisoned themselves. The pirates were not above killing those who resisted however, often using inventive and callous ways, after which a portion of the victim’s body would be returned. The Barbary Coast had, after all, drawn its name from the word barbarous, its inhabitants considered barbarians.

In 1786 the United States Congress of the Confederation agreed to the payment of tribute to the Barbary States, since American ships were no longer under the protection of the Royal Navy. The tribute was gratefully collected by the Beys, Deys, and Pashas allegedly ruling the Barbary States, who then allowed the seizure of ships flying the Stars and Stripes to continue. In 1797 $1.25 million was sent in tribute, while American ships continued to be seized and American citizens held hostage for ransom or sold into slavery. American outrage against the Mohammedans grew.

In 1794 the United States authorized a standing navy and the construction of six frigates to be its core was begun shortly after, following the usual delays imposed by Congress. Other ships were built by communities under subscription and given to the US Navy, including USS Essex, and USS Philadelphia. The young American Navy acquitted itself well in a brief conflict with Revolutionary France known as the Quasi-War. In 1801 the Navy was for the most part lying idle in American ports. That year President Thomas Jefferson, thoroughly fed up with the payment of tribute and Mohammedan treachery, ordered an American squadron to the Barbary Coast.