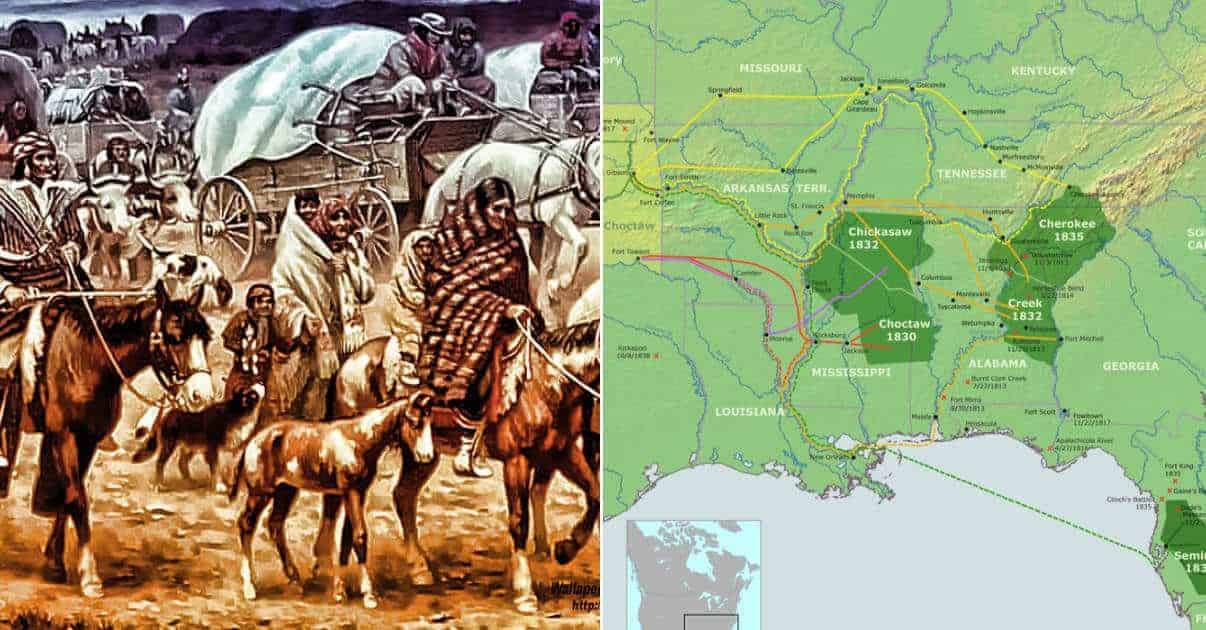

The tribe most often associated in the public mind with the tragic events of the Trail of Tears is the Cherokee. They were not the only tribe forced from their ancestral land to locations west of the Mississippi. The Choctaw had their own Trail of Tears as did the Chickasaw, Seminole, and Creek. The forced relocations led to a decade long war with the Seminole in Florida, after that tribe’s delegation signed a treaty of peace and relocation, having inspected their new lands and finding them to be acceptable. The events set in motion by the Indian Removal Act in which the tribes were forced off their lands ran from 1830 to 1850.

George Washington had decades before proposed the assimilation of the eastern tribes through a process of transforming their culture. The process gained traction in the American South, some Creek Indians especially embraced the individual ownership of land, and many Indians occupying both private and communal lands owned slaves. Indians living on privately owned land were not affected by the relocation and were allowed to remain in the East. Beginning with the removal of the Choctaw in 1831, the Trail of Tears refers to more than a pathway, but to two decades of policy which led to the deaths of thousands, from malnutrition, disease, murder, drowning, and sometimes simple exhaustion.

Most of the actual migrations were led by the tribal leaders themselves, rather than the US government. Here are some events and facts about the Indian Removal Policies which led to the Trail of Tears.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830

The remaining Eastern American Indian Tribes, particularly in the South, mostly lived communally on land which in some cases crossed state lines. Legally, state governments had no authority to deal with the Indians, a right guaranteed to the federal government by the Constitution. As demand for southern cotton grew so did the need for more land on which to grow it, and some Indians had their own plantations, on land either leased or owned. Most did not, preferring the communal style of living which had been their tribal tradition.

In 1830 Andrew Jackson pushed Congress to pass legislation which would empower the President to remove the Indians from the land they occupied and relocate them to lands west of the Mississippi, just above the Mexican province of Texas. Jackson is frequently condemned for this action, but it was in response to intense pressure from the white population of the South and their representatives. Opposition to the plan was led by David Crockett of Tennessee, and Congressional debate was heated but the act passed, with Jackson presenting his views in the 1829 State of the Union address and in letters to his supporters.

Jackson expressed the view that the Indians’ way of life could not be maintained within the confines of the states, with pressures on both game for sustenance and land for crops eventually extinguishing tribal life. Those Indians who had adopted individual land ownership were allowed to stay where they were if they wished, but those who preferred their traditional manner of existence needed to be outside the physical jurisdiction of the individual states, and on land over which the federal government held full jurisdiction. Jackson viewed the often expressed notion of preserving the Indian’s way of life as romantic nonsense incompatible with progress.

Another problem Jackson was dealing with was the state governments. Although the Supreme Court ruled that the individual states’ held no jurisdiction over the Indian lands within their boundaries, Jackson was concerned that states’ rights advocates would eventually lead to conflicts between state militias and federal troops sent to enforce federal laws. Jackson had another challenge to federal supremacy on his hands, the Nullification Crisis in South Carolina, and in his mind the presence of conflict with the state’s over the Indian lands could add to the challenge to federal law. He believed that removal to the Indian lands (present day Oklahoma) was for the benefit of the Indians, the states, and the federal government.

Jackson is often blamed for the sad events of the Trail of Tears and he certainly bears his share of responsibility for what ensued during the forced relocation. The Indian Removal Act was not intended to exterminate the Indian tribes but was an attempt to allow them to maintain their traditions without the steadily increasing pressure on the lands they occupied. The tragic events which followed were due to a variety of factors including inept or corrupt management of the removal, prejudices and racial hatreds, bad weather, insufficient supply, and in some cases outright murder.