In the 1970s, many criminologists predicated that a rising class of African American criminals, operating out of New York City and known as the “black mafia”, would become the dominant force in American organized crime. It was a reasonable prediction at the time: the Italian mafia was steadily losing neighborhoods it once ran, and its bastions in Brooklyn, Harlem, Chicago, Philadelphia, and numerous New Jersey townships, were coming under the control of black criminal. As it turned out, the predictions were off, and by the 1980s, the black mafia had ceased to exist. Between its appearance and disappearance, however, there was quite a tale.

Following are ten fascinating facts and figures from New York’s black mafia:

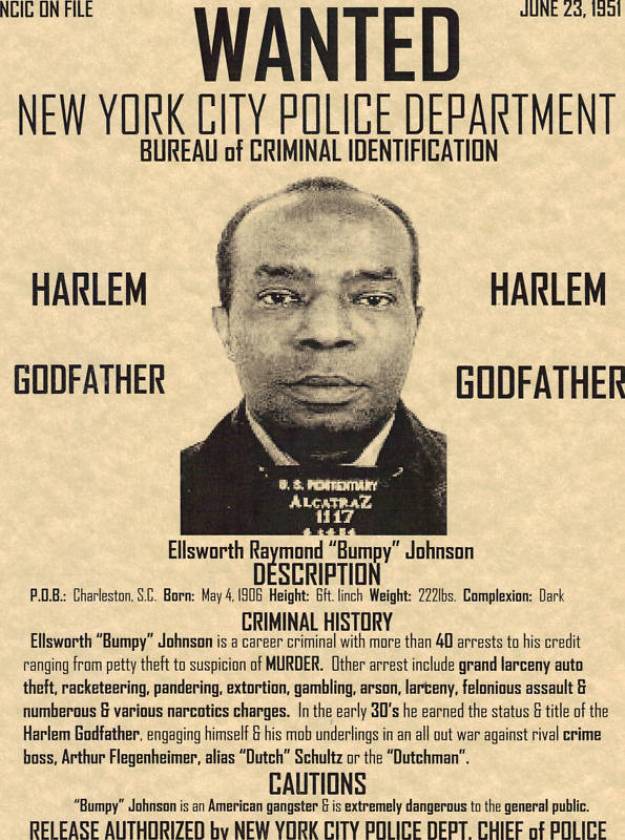

Bumpy Johnson, Harlem’s Greatest Crime Boss

From 1930 until his death in 1968, Ellsworth “Bumpy” Johnson was Harlem’s most feared crime boss. Born in South Carolina in 1905, he got his nickname from a bump in the back of his head. When he was 10, Bumpy’s older brother killed a white man and fled to the north to escape a lynch mob. Bumpy’s temper and refusal to abide by the day’s racial codes, particularly the deference to whites part, made his parents fear that he would end up killing somebody or get lynched. So at age 14, he was sent to live with a sister in Harlem.

In Harlem, Bumpy joined a protection racket that shook down local stores, then got his big break when he was hired as a leg breaker by Madam Saint Clair, Harlem’s biggest bookmaker and reigning crime queen. He eventually became a numbers runner, then a bookmaker. When mobster Dutch Schultz attempted to take over Saint Clair’s bookmaking in the early 1930s, Bumpy Johnson was her point man in a gang war that lasted until Schultz’s assassination on mob boss Lucky Luciano’s orders in 1935.

After Schultz’s demise, Bumpy negotiated a deal with Lucky Luciano in the 1930s, by which Harlem bookmakers retained their independence in exchange for a cut to the mafia. It was the first time a black man had cut such a deal with the Italian mob, and it made Bumpy Johnson a respected and somewhat heroic figure in the neighborhood. Thereafter, he was the main associate of the Luciano (later Genovese) mafia crime family in Harlem.

Bumpy Johnson was feared and revered in Harlem for decades. He became friends with famous figures such as Cab Calloway, Billie Holliday, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Lena Horne. His activities were reported in the celebrity sections of magazines such as Jet. He was also Harlem’s criminal kingpin, whose approval every hood needed in order to operate in that part of town. He did 9 years in Alcatraz from 1954 to 1963, and was greeted with a parade upon his return.

Yet, despite his flashy fashion, his poetic pretensions, and ostentatious distribution of turkeys to the poor on Thanksgiving, he never joined the pantheon of famous American villains. This, notwithstanding that the stock gangster boss character in every blaxploitation film, starting with “Bumpy Jonas” in Shaft, is modeled on him, or that the entire gangsta rap genre is essentially a homage to Bumpy Johnson.

He almost certainly murdered and ordered the murder of more people than, e.g.; John Gotti, Jesse James, Billy the Kid, and perhaps even Al Capone. He certainly ran his criminal empire for far longer than any of them ran theirs. The fact that he was black, and so were most of his victims, is a factor in explaining why he is not as well known as other iconic American criminals. His exploits did not resonate far beyond Harlem. Another factor is that there was something cold and reptilian about him: most famous criminals were hot and passionate. Bumpy Johnson, by contrast, quietly made his victims disappear, like Al Capone’s successor Frank Nitti – another crime boss who ran his criminal kingdom for decades, and died of natural causes while free.

He died of a heart attack in a Harlem restaurant, clutching his chest and keeling over around 2 AM in the morning of July 7th, 1968. His death was dramatized in the movie American Gangster, which depicted him expiring in the arms of his surrogate son and successor, Frank Lucas, who would revolutionize New York’s drug trade. Bumpy Johnson had dominated the Harlem crime scene for decades, maintaining some measure of order on the street. After his death, various contenders scrambled to fill his shoes. Their competition, and a desire to control it and keep things from getting out of hand, would lead to the rise of the black mafia.