It was neither a railroad nor did it run under ground, but it did have stations, conductors, and carried what was called cargo or freight. Its members operated a series of secret routes to freedom used by escaping slaves that ran to the north, though in the beginning there were routes to Spanish Florida and from Texas to Mexico. It was illegal, the Fugitive Slave Act required citizens to aid slave owners who were trying to recover their property, and in 1850 slave catchers were allowed to operate in the free states, with local officials providing them assistance if requested.

Abolitionists assisted the escaped slaves in a variety of ways, hiding them, moving them from point to point on the railroad, providing food, and in some cases identity papers. The system was supported by many free blacks – some manumitted former slaves – without whom the system would have had little chance of success in helping slaves escape. After the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law was enacted, several of them were kidnapped by slave hunters and taken into slavery. Some black conductors on the railroad willingly entered plantations of the South to recruit escapes and lead them to points on the railroad.

Here are ten events, places, and people of the Underground Railroad.

How the Underground Railroad worked

For the most part slaves escaping from southern plantations via the Underground Railroad moved in small groups, over relatively short distances each night. Thus fewer slaves in the deep southern states were able to escape than those from the states closer to the Ohio River, which was called the River Jordan by escapees. There were escapes from the deep southern states, but slave and bounty hunters caught the vast majority of them. After the Pearl incident, in which 77 slaves attempted to escape from Washington DC in the sloop Pearl, the recaptured slaves were sold to plantation owners of the Deep South as punishment.

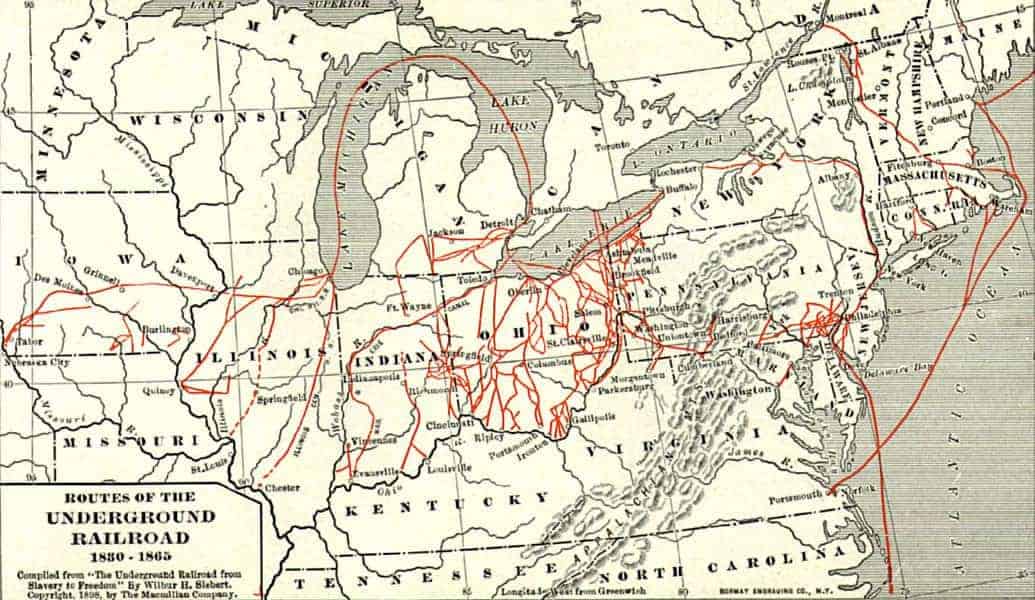

Because of the prevalence of slave hunters the escape routes of the Underground Railroad were deliberately circuitous, with the intent of confusing pursuit. An escaping slave moved from station to station, traveling at night, often accompanied by a conductor but sometimes moving alone. Stops on the route were called stations, run by abolitionist sympathizers known as stationmasters. The railroad was not a safe journey for small children, and many escaping slaves left their families behind, hoping to gain their own freedom and earn enough to possibly buy the freedom of their family. Since the courts could force slaves to be returned to their owners this could only be accomplished from Canada or Mexico.

The slaves were not only pursued by the professional bounty hunters known as slave catchers. By law, Federal Marshals were also required to capture escaped slaves, taking them into custody for the matter to be adjudicated by the courts. After 1850 escaped slaves were denied the protection of the courts. The need for secrecy, especially regarding the location of the stations, required that information was never passed in writing or maps, instead being passed along via word of mouth. Slaves caught on the railroad were rigorously grilled over the manner of their escape and who had assisted them, especially on the southern routes of the railroad. In the northern routes the Marshals were often more sympathetic to the escapers and protected them from the slave catchers.

Not all areas of the North were sympathetic to the plight of escaping slaves however, and in many areas laws prohibited the presence of free blacks as well as escaping slaves. The state of Indiana amended its constitution to bar free blacks. Many sections along the Ohio River were populated by former southerners who assisted the slave catchers by patrolling roads at night. The high demand for slaves during the 1840s through 1861 made the capture and return of slaves highly lucrative, given the size of the rewards offered by southern slave owners. The operation of the Underground Railroad cost money too.

Sympathetic abolitionists and churches were the primary financial backers of the Underground Railroad. They and most of the participants in the Railroad were typically aware of just their own small section, in order to preserve secrecy and security. Since aiding an escaped slave was illegal, local groups were deliberately kept small. Fewer participants decreased the risk of the activity being compromised. Stationmasters alerted each other of cargo on the railroad using coded messages of when to expect an arrival, and how many were on the way. The ultimate goal of the escaped slaves was the United States – Canadian border.