The first Vice President of the United States eventually became President. The second Vice President did the same. The third Vice President survived indictments for both murder and treason at different times, though not while serving in office. And so it goes. There have been more Vice Presidents, 48 as of this writing, than Presidents and with the exception of those who ascended to the Presidency or won it on their own, they are virtually forgotten. It has been throughout American history a thankless job, a more or less useless job, and until fairly recently a forgotten job.

The American Vice-President presides over the Senate but casts no vote there, except in the case of a tie, which throughout history have been rare. The only duties specified to the office by the Constitution are presiding over the Senate and supervising the counting of the votes of the Electoral College. There is no official residence which comes with the position by law, but since 1974 the Commanding Officer’s residence at the US naval Observatory has served the purpose. Prior to the passage of the 25th Amendment, which defines Presidential succession, the nation went through many lengthy periods with no Vice-President, and seemed to have no difficulty with the office empty.

Regardless, some Vice-Presidents have made their mark on the nation, though most people today have never heard of them. Here are ten Vice-Presidents of the United States, largely forgotten to history.

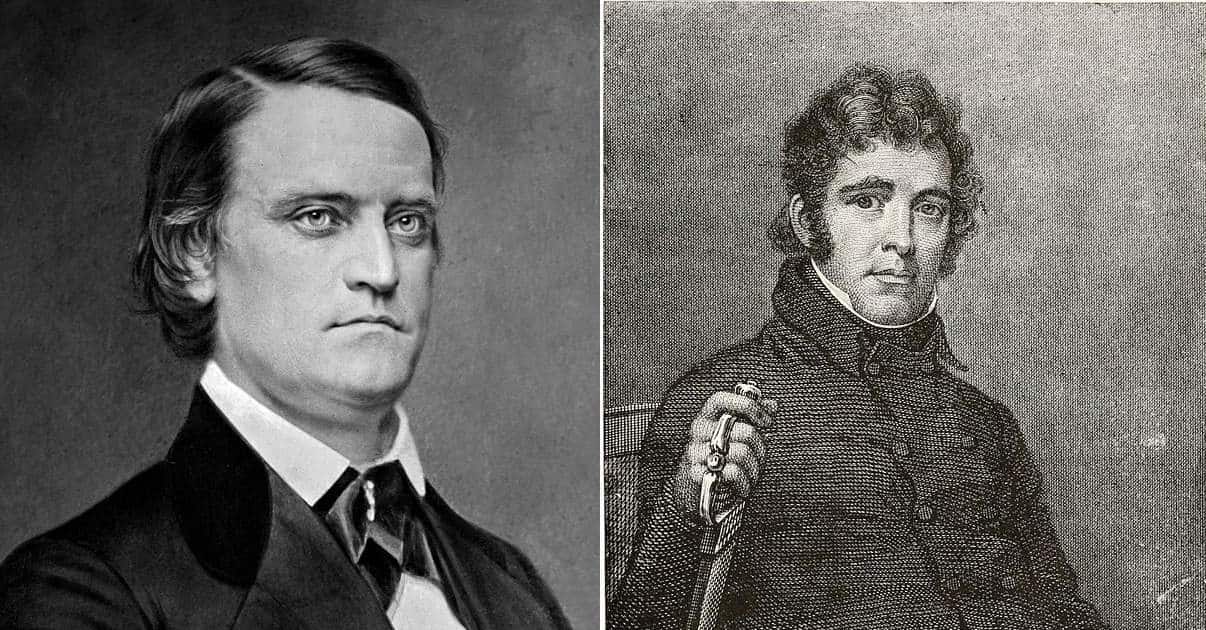

John C. Calhoun

John Calhoun was a South Carolinian whose political skills were such that he served consecutive terms as Vice President under two Presidents of opposing political views, John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. Calhoun was able to align himself with any political party, determined to represent his own views rather than those dictated by party leaders. He believed that the states had the right to overturn or “nullify” federal laws if the majority of the people within the state agreed, and his leadership on the issue of nullification led to the first of the secession crises which plagued the government in Washington during the antebellum years.

Although he was born and grew up in South Carolina, Calhoun was educated at Yale, and following his completion of a degree there he studied at Tapping Reeve, the first and then only school in the United States dedicated to earning a law degree (most states required the study of law under the tutelage of a practicing attorney, known as reading the law). He served in both the House and the Senate, and also as Secretary of War in the Monroe administration, where he was the first to suggest the relocation of the eastern Indian tribes to lands west of the Mississippi, where they would be able to preserve their way of life without impedance from encroaching white settlement.

In 1824 the Electoral College selected Calhoun as Vice President in a landslide, but failed to elect a President. The House of Representatives elected John Quincy Adams as President. As Vice President, Calhoun stood in opposition to the White House on many issues, including tariffs and federally subsidized roads, canals, and other projects. While serving as Adams’ Vice President Calhoun wrote to war hero and former Presidential candidate Andrew Jackson that he would support another Jacksonian candidacy in the election of 1828, should the General decide to launch one. It would prove to be a political mistake for Calhoun.

Jackson ran with Calhoun as his running mate, and won the Presidency. Surprisingly, Calhoun was not the first VP to serve under two Presidents, George Clinton had served under both Jefferson and Madison, but they were of similar political persuasion, where Jackson and the defeated John Quincy Adams were decidedly not. Calhoun organized the wives of Jackson’s cabinet members to ostracize Peggy Eaton, wife of John Eaton, Jackson’s Secretary of War, in what became known as the Petticoat Affair. Calhoun and others accused Eaton and his wife of having been involved in an adulterous affair prior to their marriage and the resulting scandal ended his relationship with the President.

Jackson responded to the affair by firing his entire cabinet, which destroyed any influence Calhoun had over the administration. Calhoun’s support of the principle of nullification placed him in an opposite position to the President, and when Martin Van Buren was elected Vice President, with Jackson as President, in 1832, Calhoun resigned rather than finish his term and returned to the Senate. He was one of two Vice Presidents to resign his office, the other being Spiro Agnew in 1973. Calhoun remained a potent political force for the remainder of his life, serving as Secretary of State and as a Senator from South Carolina, an unrepentant supporter of slavery being what he called, “…a positive good.”