It wasn’t just ordinary Germans or Italians who cheered their authoritarian leaders in the 1920s and 1930s. Outside of the countries that were taken over by far-right regimes, plenty of people looked on in admiration. Some were even jealous and hopeful that fascism would triumph in their country. As remarkable as it might seem now, prior to 1939, many intellectuals, including men and women of letters as well as scientists and celebrities, thought Mussolini, even Hitler, offered the answers.

In some cases, a profound fear of Communism led many to believe that far-right politics offered the only hope for the future. This was especially the case in Britain, where many aristocrats felt that England and Germany had a close, historical bond and that war could be avoided. At other times, however, some prominent individuals simply loved the idea of authoritarianism, hoping that they too could be part of a ruling elite. And then, of course, there were the racists and bigots who looked on approvingly as Hitler persecuted Germany’s Jewish population.

Often, such flirtations with the far-right were short-lived. As the true nature of Nazism became clear, and as it became apparent Hitler would never be appeased and that war was inevitable, many quickly abandoned their friendly attitudes to fascist regimes. But sometimes there was no about turn. Indeed, in some extreme cases, famous writers and prominent political figures even carried on supporting fascism and Nazism long after the end of the Second World War.

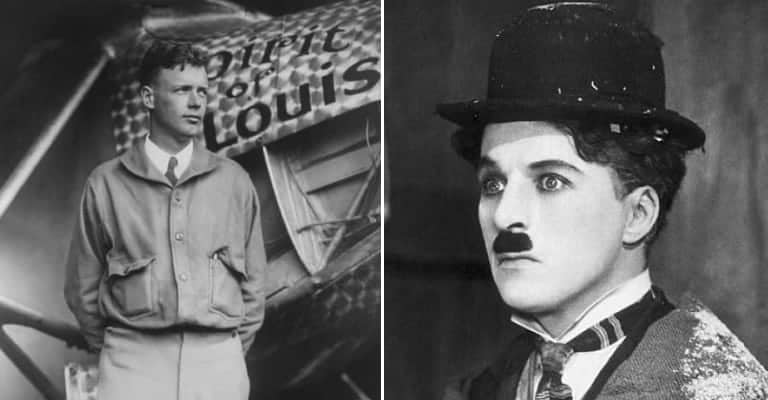

So, from aviation legends to Hollywood screenwriters, and from Dukes to authors, here we have 19 famous figures who flirted with fascism:

19. Henry Ford was awarded one of Nazi Germany’s top honors for his collaboration with the evil regime – as well as for his virulent anti-antisemitism.

As early as 1924, Heinrich Himmler – who would go on to become one of the Nazi regime’s most brutal killers – described Henry Ford “one of our most valuable, important and witty fighters”. While the industrialist may not have openly expressed his admiration for Nazism like some of his fellow Americans did, the regime’s antisemitic views were certainly aligned with his own. Moreover, Hitler was a huge admirer of Ford. It was said the Fuhrer kept a picture of the automotive tycoon on his desk and wanted to model the German economy on a Ford factory.

Ford never attempted to keep his antisemitic views a secret. In 1920, he released his infamous collection of essays The International Jew, the World’s Foremost Problem. At the same time, Ford also used his fortune to help distribute The Protocols of the elders of Zion across the U.S., a slanderous forgery used to stoke up antisemitic hatred. Unsurprisingly, he welcomed developments in Germany and, when the world was waking up to the evils of Nazis, continued to trade with the regime. For his support, the Nazis awarded Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, complete with a personal note from Hitler himself, for his 75th birthday.