The European domination of Africa was preceded by several stages. The first was coastal trade, the second the export of religion and the third exploration. It was the Portuguese, under the sponsorship of the great King Henry the Navigator, who began the first modern exploration of the coast of West Africa. By the middle of the 15th century, Portuguese trade depots were established all along the west coast of Africa, founding the infamous Atlantic Slave Trade.

Before long, other European trading powers were competing in the same grim trade. Exploration into the interior, however, was often limited by an atrocious climate, rampant disease and powerful local tribes. It was not until the latter half of the 19th century, and the development of effective anti-malarial prophylactics, that any meaningful penetration of the interior took place. The first to do so were missionaries, but very quickly European hunters, explorers and adventurers began to probe the interior, and soon the intimate geography of Africa began to be mapped and understood.

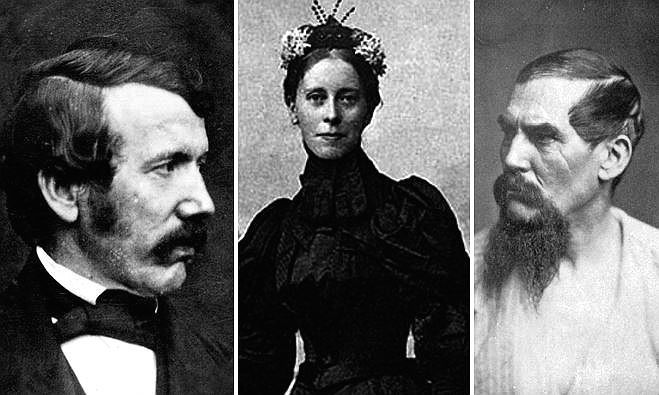

Even with the aid of modern medicine and the protection of firearms, the business of setting foot into the interior of the ‘Dark Continent’ was a risky business, and it took a special kind of man, and a special kind of woman, to make that journey. Here are our Top Ten feats of African exploration.

Mary Kingsley

We kick off with Mary Kingsley just to get the juices flowing. Mary Kingsley was a lifetime achiever, and a pathfinder in a field very rarely open to women. She entered the exclusive pantheon of African explorers rather late – in the last decade of the 19th century – when most of the great discoveries had already been made, but her contribution was perhaps more in the founding of an African academia. She promoted interest in African art, fetishism, anthropology and ethnography as orthodox fields of study, and although her journeys of exploration were relatively minor, her social contribution was incalculable.

Mary Kingsley was born into a conventional British, Victorian family, and the expectations placed on her reflected that. She was expected to marry, so her education was minimal, and when her parents fell ill, she was expected to sacrifice marriage to care for them. To these expectations she was faithful, and it was not until 1893, at the age of thirty-one, that she followed her fascination, landing on the coast of West Africa for the first time.

Her first visit was to the slave colony of Sierra Leone, a relatively easy entry, but before long she was in the Portuguese territory of Angola, living with local people and absorbing, studying and documenting their culture. Unlike a great many explorers of the age, Mary Kingsley’s expeditions were low-key and unpretentious, and intended primarily to shed a light on the ethnic and cultural minutia of Africa.

Her signature expedition was an 1894 solo canoe journey up the Ogooué River in Gabon, one of the most forbidding regions of Central Africa. There she collected specimens of previously unknown fish, three of which were later named after her. She discovered, and began a detailed study of the Fang people, as her first, major anthropological project, becoming in the end a recognized expert on African cults and fetishism. She later published and lectured widely.

It all ended for Mary Kingsley on the battlefields of the Anglo/Boer War. She was a member of a new generation of humanist, socially active women, not only fighting on behalf of dispossessed African in the growing frenzy of colonization, but also the victims of Britain’s brutal war tactics. In 1900 she joined the great British humanitarian and feminist Emily Hobhouse in South Africa, caring for the victims of British concentration camps. In June 1900, she contracted typhoid, rampant in the camps, and died.

Mary Kingsley’s legacy as an African explorer was to found the early humanitarian movement, pointing out what had been done to Africa by over 300-years of slavery, and what was continuing to happen under the news, but no less exploitative practices of colonization. She was, therefore, in the context of her times, an early human rights activists, and one of the first to use her celebrity to put that message across.