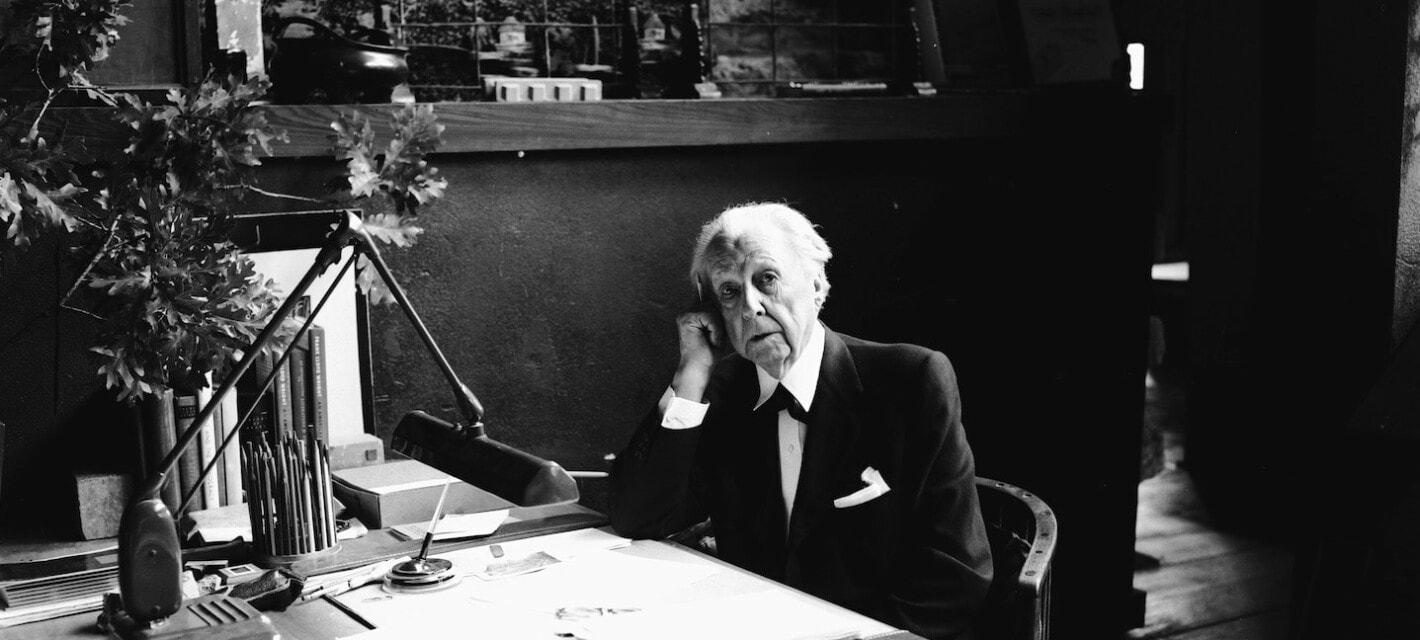

Frank Lloyd Wright is considered one of the most influential architects of modern history, moving design from the excessive Victorian era to the toned-down modern era. There is an inexhaustible amount of literature about his work. But for those who knew him outside of this drafting table, it was easy to get caught up in the tornado that was his life.

While he worked on some of the grandest buildings in the world, his personal life was often a mess and he courted scandal. It is possible to have an extraordinary talent to share with the world while being inherently flawed as a person. Wright is not the first public figure to prove that. The flaws coexist with the talent. It is not two sides of a coin – it is two sides of a 20-sided dice, each unique side contributing to the whole.

Wright Was From Rural Wisconsin

As famous as Wright is today, he did not start off from a place of great wealth or privilege. He was born in 1867 to a Baptist minister/ musician, William Carey Wright, and schoolteacher Anna Lloyd Jones Wright. He grew up in central Wisconsin on the lands settled by his mother’s family. The family had a fighting, independent spirit, with their own motto, “Truth Against the World.”

Young Frank had the run of the rolling hills along the Wisconsin River as he played and explored, seeking his own truth in the world. He helped on the Lloyd Jones farm, “working from tired to tired,” tending the animals and watching the cycle of growth, death, and rebirth. He watched how the sun changed the landscape and everything in it. His time in Spring Green would give him a love of nature, which would have an enormous impact on his architectural career.