“Let me tell you a little story about a man named Jed. A poor mountaineer barely kept his family fed…” The bouncy, banjo-heavy tune brought Jed Clampett and his family of upwardly mobile hillbillies into American living rooms in the 1960s. The show was a classic comedy about backwoods, simple hillbillies trying to navigate high-culture urban life. Thanks to these popular culture tropes, ‘Hillbilly’ is an offensive slang term for people of the rural Appalachian regions.

It is full of colorful characters, great food, progressive union movements, and unique popular culture (for better or worse). “Hillbillies” themselves are diverse in their political, religious, and social beliefs. While the modern “hillbilly” label has taken on political undertones and identity, it hasn’t always been that way. Delve into the background of hillbilly culture, including the roots of its stereotype, some of its famous moments and people, and cultural contributions.

The Stereotype

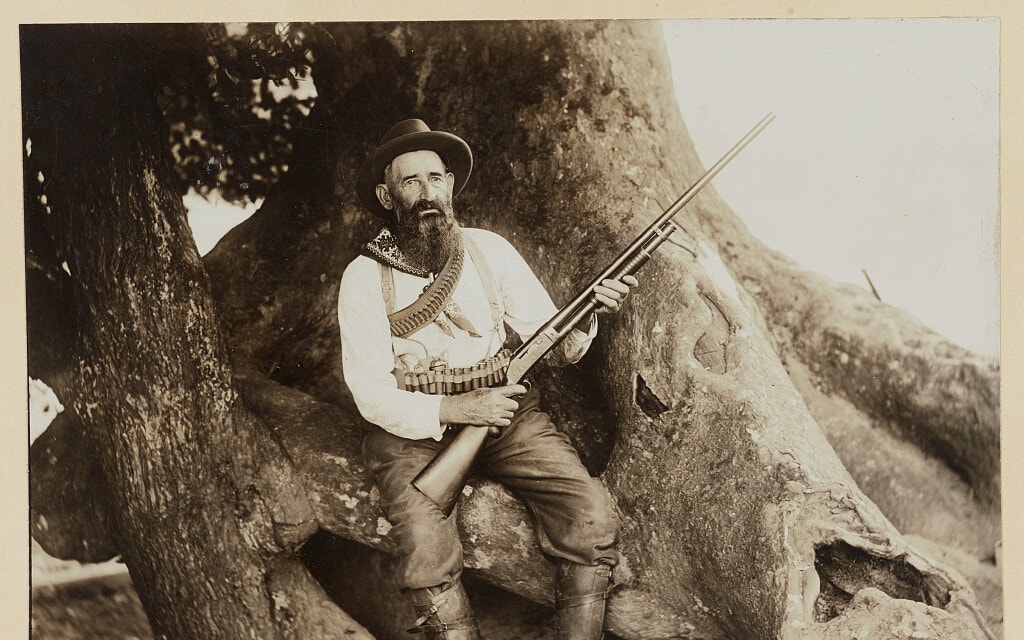

The hillbilly stereotype is a caricature of a Caucasian impoverished underclass in the rural mountain and hill areas of the southeastern United States. Stereotypical hillbillies have little interest in modern technology. They are happily, even willfully, undereducated. Due to a lack of education, they are simple-minded, with a slow drawl that sounds like a separate language. They are poor and uninterested in changing that situation. They are often drunk, unkempt; their clothes old and tattered.

Hillbillies run around barefoot, except on special occasions. Their hair is untidy, dirty, and often lice-infested. Inbreeding is rampant, with large families of cousin-siblings who might be their own grandfather (which contributes to the simple-mindedness). The stereotypical hillbilly is the antithesis of the modern, tech-savvy urbanite, with their well-groomed hair and clothes, elevated level of education, and money to burn. But as with most stereotypes, reality doesn’t match the caricature.