The US Marines’ Historical Predecessors

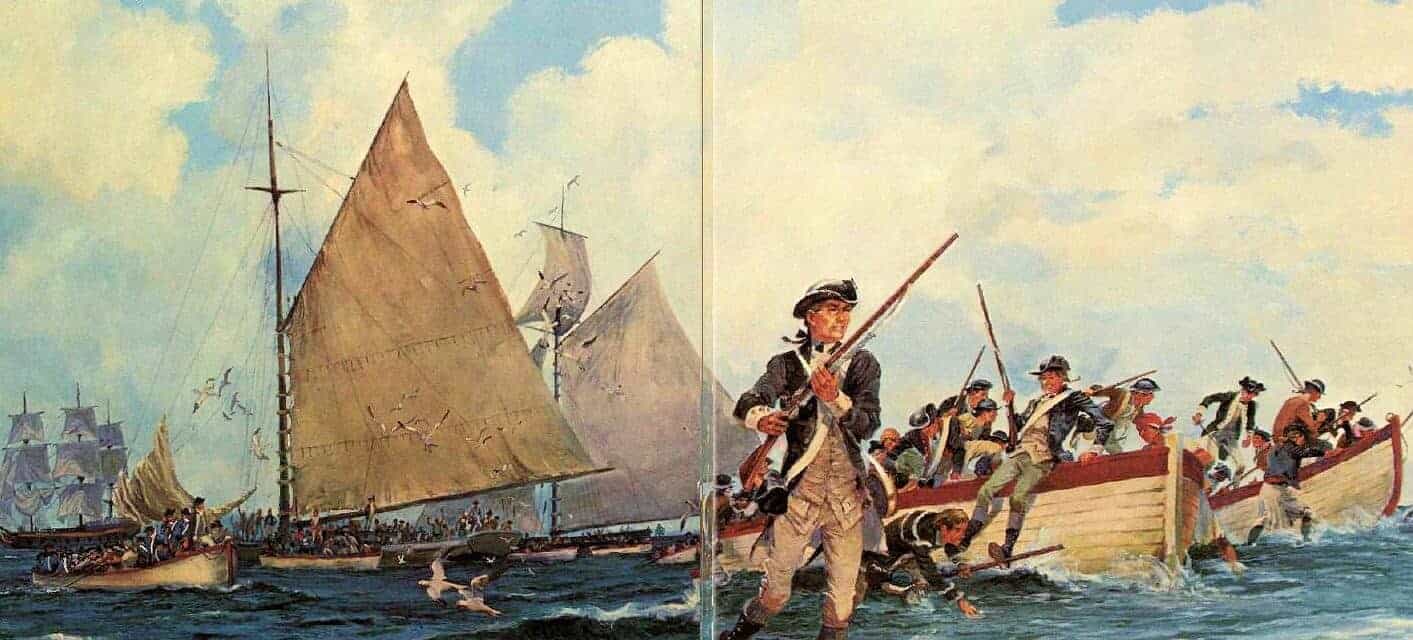

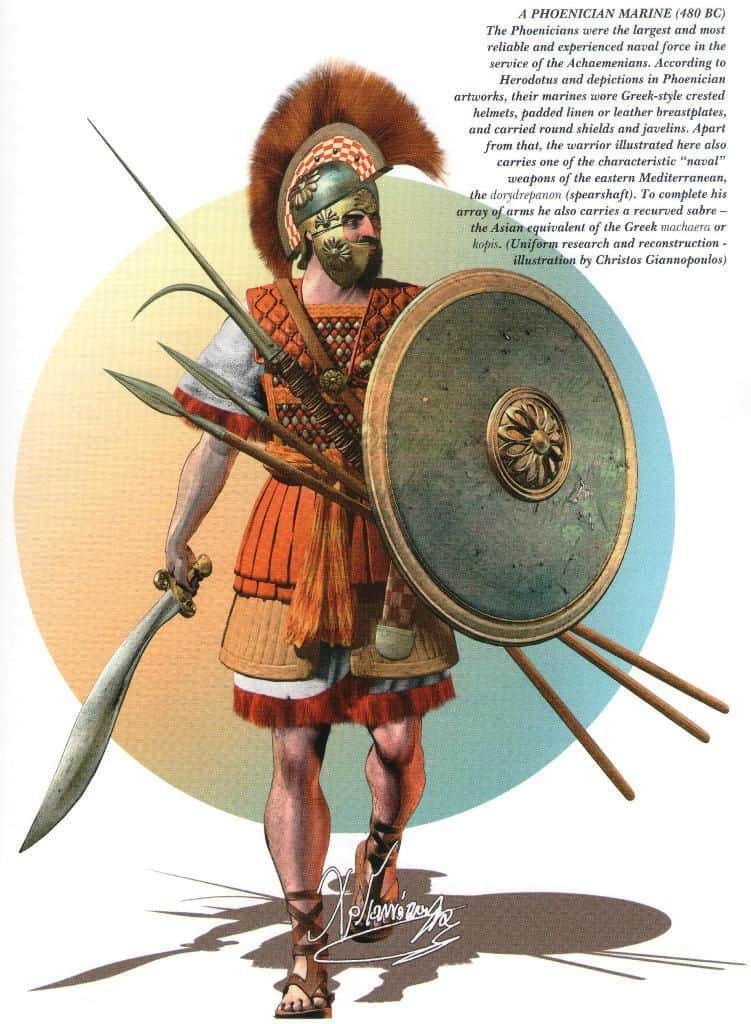

Ship borne infantry that specializes in supporting naval operations, otherwise known as naval infantry or marines, have been around for thousands of years. In the early days of naval warfare, sailors doubled as soldiers in a pinch, until the ancient Phoenicians introduced complements of soldiers whose primary tasks were not the care, maintenance, and operation of ships. Instead, the duties of these specialists revolved primarily around boarding enemy ships and warding off enemy boarders from their own vessels, or conducting amphibious operations by disembarking to attack and raid targets on land, then returning to their vessels.

Before long, others around the Mediterranean basin began copying the Phoenicians, and took to employing their own ship borne infantry. By the late 6th century BC, marines were a common feature in the Eastern Mediterranean. The ancient Greeks took the idea and ran with it, and as early as the 5th century BC, they began introducing heavily armed and armored hoplites on their triremes for the specific purpose of boarding enemy vessels. The Athenians, in particular, refined the concept, and built themselves a sea empire around the Aegean and Black Sea, with marines playing an integral role in their naval strategy and tactics.

The Romans – who learned the concept from both the Greeks and Carthaginians against whom they fought protracted wars – developed and took naval infantry even further. Landlubbers, the Romans were excellent soldiers but poor sailors, and they discovered during the First Punic War (264 – 241 BC) that they were no match for the highly experienced Carthaginians in seamanship and naval tactics. So they hit upon the innovative idea of transforming naval engagements into de facto land battles. The Romans accomplished that by modifying their ships with a device called a corvus (crow), that was basically a plank on a pivot with a heavy metal beak, that was dropped on an enemy vessel when it drew near, penetrating its deck and securing it to the Roman ship. Roman naval infantrymen – Marinus – would then cross over the plank, slaughter the enemy sailors and rowers, and capture the ship.

In the middle ages, the Venetians, masters of a maritime trade empire that would eventually capture and sack Constantinople in 1204, then go on to rule Byzantium for over half a century, created a well organized marine corps. Known as the Fanti da Mar (sea infantry), the Venetian marines were comprised of 10 companies, that could be combined to form a marine regiment that supported naval operations with amphibious landings and ship borne combat.

During the Age of Exploration, the Spanish, masters of the world’s first far flung global empire upon which the sun literally never set, formed the Spanish Marine Infantry in 1537 – the oldest marine corps still in existence. Other European naval powers followed suit, including the British, whose Royal Marines – the model upon which the Americans would draw a century later, when forming the naval infantry that eventually became the United States Marine Corps – can trace their origins back to 1664.

By the 18th century, naval service, particularly in the British Royal Navy, often entailed long voyages that could last for years. Living conditions aboard ship were often abysmal, and the crews included many sailors who had been forcibly press ganged into serving king and country. As Winston Churchill described it, life in the Royal Navy back then boiled down to “rum, buggery, and the lash“. That led to an evolution in the role of marines: in addition to their traditional functions, the marines now also served as the captain’s armed muscle aboard ship. Quartered apart from and treated differently than the rest of the crew, marines kept the often brutalized and miserable sailors in check, preventing them from rising up in mutiny and murdering their officers.