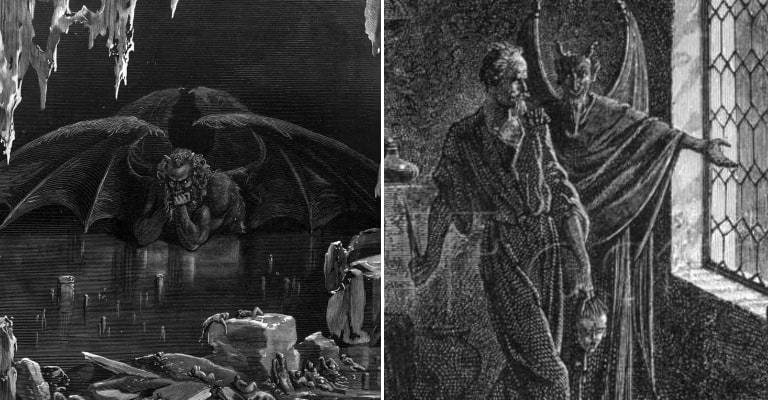

Satan. The Devil. Beelzebub. Lucifer. The Great Deceiver. Old Scratch. Call him what you like, The Devil has equally terrified, tormented, and fascinated mankind for millennia. Surprisingly, given his place in Christian religion and Western culture at large, there is precious little about his dark majesty in the Bible. The Old Testament has only ten references to him, and though there are more in the New Testament, his traditional biography is actually from the Apocrypha (non-canonical religious texts), where the Book of Enoch describes how Satan and his rebel angels angered God through their pride and were thrown from heaven.

This is the story of Satan popularised through Christian teaching, backed by an allusive passage in the Book of Revelation. However, whilst the Bible is not so interested in the fallen angel, mankind has been far more preoccupied with him. People were frightened of The Devil, and many events and landscape features were attributed to him. Many people also claimed to have seen Lucifer in everyday life, generally having a rare old time in pubs or the theatre. So let’s have a look at what he’s been up to since he was last seen tempting Christ in the wilderness.

Satan Bends a Spire in Chesterfield

The Church of St Mary and All Saints, Chesterfield, is a 14th-century church with an eccentrically-crooked spire that one church historian has praised as ‘the most famous architectural distortion north of Pisa’. Its peculiar shape is widely-attributed to Beelzebub. In one version, Satan was sat on the church tower, with his tail twisted round the spire for support. A virtuous bride was getting married that day, and the event was so unusual that Satan turned round, jaw agape, to stare at the marvel. As he did so, the spire twisted with him, and was never the same again.

Another version of the story has The Devil sat in the same position, probably looking for people to trick into sin, whilst a church service was taking place beneath him. Suddenly, a whiff of incense came from the church, making him unleash a thunderous sneeze. The force of Old Nick lurching forward bent the spire into its current form. Another tradition relates how Satan was one day having his hooves re-shod by a blacksmith at nearby Bolow when a misplaced nail made him leap away in pain, kicking out at the unfortunate church spire as he sailed overhead.

Of course, there is a rational explanation for all this spire-bending. It was long-supposed that the spire was built by poor-quality workmen after the Black Death, which severely reduced the labour pool. Whilst there may be some truth in this, the accepted architectural theory is far more prosaic. It is thought that the workmen used unseasoned timber, which buckled and distorted under the weight of the lead cladding. The spire is exposed to sunlight on its south side every day, which has made the 33-tonnes of lead heat up and expand more than the north side, gradually twisting the eminence.