The 19th century was the century of steam power and from the 1850s onward it was the burning of coal which created the steam. Coal replaced wood as the source of heat for steam locomotives. Meals were cooked and buildings were heated with coal. Ships and riverboats used coal fired boilers to produce steam power. America’s vast coal reserves provided a seemingly unlimited source of cheap power to fuel the industrial revolution. In the eastern states of Appalachia mining coal became a major industry.

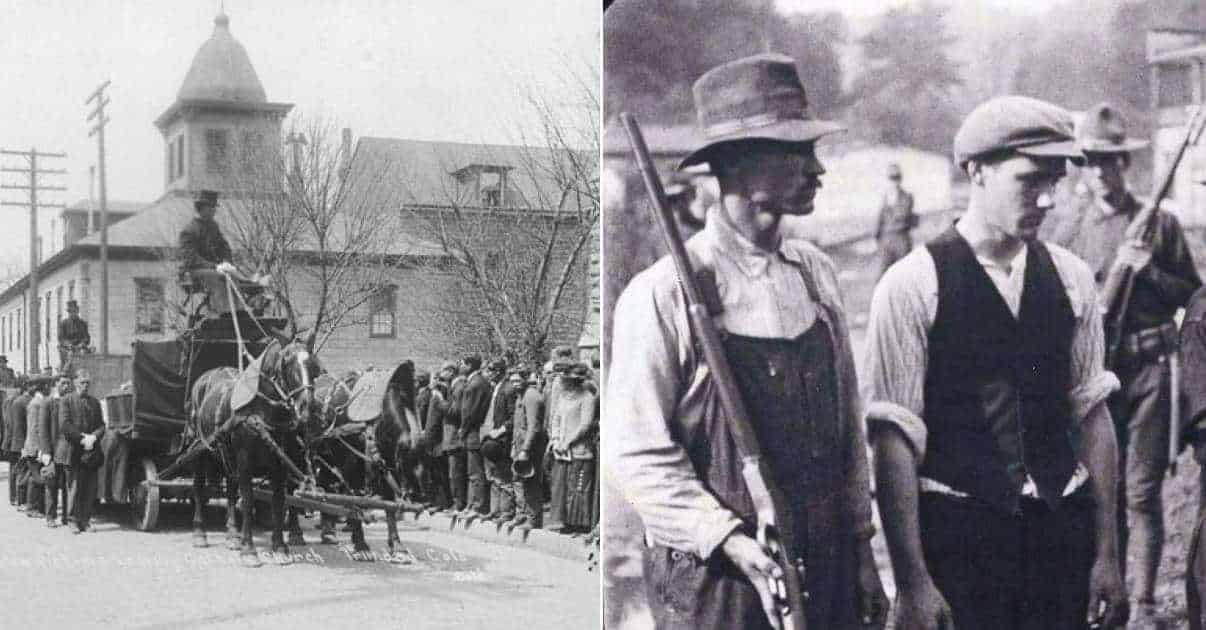

Mining coal – then and now – is a difficult, dangerous, and dirty job. Coal miners worked long hours in frequently terrible conditions earning low pay. Coal companies exploited the workers by avoiding organized labor. Miners frequently lived in company towns, purchasing life’s necessities in company stores, with security provided by company employees. Beginning in the 1870s and through the early years of the Great Depression, mine workers sought to overthrow the system through the establishment of organized labor. The coal companies opposed them with tactics which included intimidation, sabotage, extortion, and murder. Armed conflicts between labor organizers and hired security forces were common. The conflict became known as the coal wars, and was mostly felt in Appalachia, although Colorado and Illinois too had major incidents of violence.

Here are ten little known events which occurred during the Coal Wars, the impact of which is still felt today in the coal producing regions of the United States.

Bituminous Coal Miner’s Strike of 1894

Bituminous coal is mined from both surface and underground mines throughout the Appalachian region, as well as in Illinois and Colorado. By the 1890s nearly half of all Navy ships in the world which burned coal to produce steam were using Pocahontas Bituminous coal mined in southwestern Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky, making it a major export for the nation as well as a strategic war material.

The Panic of 1893, a major economic downturn worldwide, created a severely depressed market for coal as all industries cut production. Coal prices were cut drastically, and the financial pressures quickly led to lay-offs and reduced wages for coal miners who managed to keep working. In response, the United Mine Workers – founded in 1890 – demanded a general strike of bituminous coal miners in the states of Colorado, Illinois, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio. In the spring of 1894 over 180,000 miners went on strike, demanding among other concessions a return to the wage scale which had been in place the preceding spring.

The UMW at the time had only about 13,000 dues paying members; most of the strikers were not members. In several areas of the country violence broke out between striking miners and those who crossed the picket lines. Mine owners refused to restore wages to the demanded levels, although some did increase wages slightly in order to induce back some of the workers.

In LaSalle Illinois on May 24 and 25, more than 40 sheriff’s deputies and hired security personnel fought a gun battle with striking workers, and more than two dozen deputies were wounded. By July the reinforced deputies drove off more than 2,000 strikers. The day before the LaSalle confrontation began, security guards used machine guns and rifles to kill five strikers, wounding another eight, in Uniontown Pennsylvania. The National Guard was mobilized in several states to protect miners who chose to work from those supporting the strike.

In the end it was the United Mine Workers which was badly hurt by the strike. When most miners gave in and returned to work by late June, the UMW ran out of money, withdrew from the American Federation of Labor, and suspended publication of its newsletter. The Panic (economic downturns were called Panics before the Great Depression) continued for another three years, and coal production and wages remained depressed.