When talking about the founders of the United States the names Adams, Washington, Jefferson, and Franklin come to mind readily, as well as several others such as Hamilton and Madison. There were many others, political, military, and social leaders who are all but forgotten. When asked to name a signer of the Declaration of Independence how many remember Button Gwinnett, or that Roger Sherman was a member of the committee tasked with drafting that document? In fact the majority of the founders who debated and shaped the early movement for independence and the new government are for the most part forgotten, their roles ignored by history. That’s unfortunate because their contributions were significant.

Prior to the Revolutionary War civic leaders and influential businessmen contributed to the growing dissent with the British Parliament and the King of England. During and after the war influence in the formation of a government was felt coming from the newly opened territories and expanding western settlements. These leaders helped develop the new nation alongside the well-remembered of the founders, and deserve to be counted among them. Many are remembered in places which reflect their names, but the individuals and their contributions to American history are of little moment.

Here are ten of America’s Founders who are for the most part forgotten in the history books.

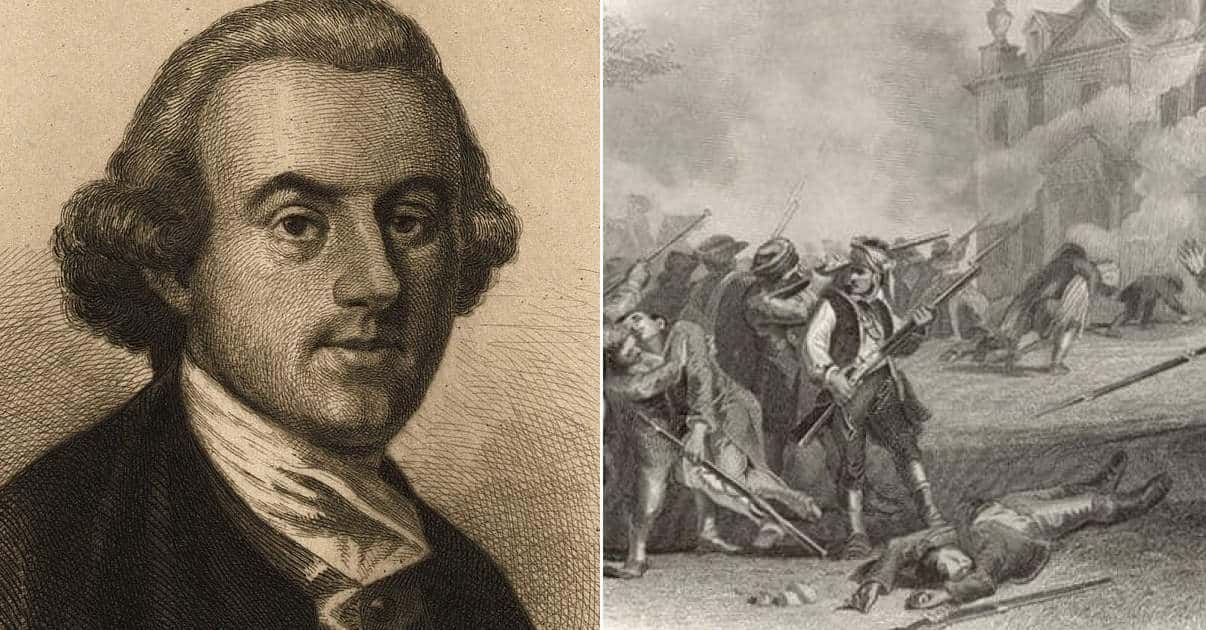

Caesar Rodney

Caesar Rodney served as a soldier, politician, and statesmen in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, becoming a leading citizen of the tiny colony of Delaware. Rodney was descended from a prosperous family, major landowners in the colony, whose eventually 1,000 acre farm produced wheat and other grains, worked by more than 200 slaves. Rodney was 27 when he entered the political arena as Sheriff of Delaware’s Kent County, a powerful and lucrative position which served as a springboard into others, and he became aligned with a political party which positioned itself against the British Parliament and its approach to taxation.

Rodney served in the Congress called to oppose the Stamp Act, and in the late 1760s he represented Kent County in the Delaware Assembly. In the mid-1770s, while still serving in the Delaware Assembly he also served in the Continental Congress, where Delaware was represented by three men, Rodney, Thomas McKean, and George Read. Rodney and McKean supported the movement towards independence. Read did not, arguing for reconciliation with England. Rodney also served in the Delaware militia suppressing Loyalist movements in Delaware, and was engaged in that duty in late June, 1776.

Rodney was in Dover when he received a message from McKean that the colonies were to vote on independence, with each colony receiving one vote. With McKean voting in favor and Read opposed, Delaware’s delegation would be forced to abstain, having not a majority. Rodney traveled on horseback the seventy miles between Dover and Philadelphia in an unbroken ride (though he changed horses), through severe thunderstorms, to arrive in the Congress still wearing spurs, and cast the deciding vote allowing Delaware to vote for independence on July 2, 1776. He later signed the document on August 2, when most of the delegates affixed their names.

The Delaware Regiment of the Continental Army was one of the best to serve under Washington, and when its commander was killed in the Battle of Princeton Rodney offered his services to succeed to the command, but Washington preferred that he remain in control of the Delaware militia. In that capacity he suppressed or dispersed several Loyalist groups, and as governor of the state he exhausted himself struggling to find financial support for Washington’s army. The governor’s office was essentially an honorific, with little authority, and it was only through Rodney’s influence in the assembly that his efforts were rewarded.

Under the Articles of Confederation Rodney was elected to Congress, but his declining health prevented him from attending after 1777. Rodney suffered from a debilitating facial cancer, which the treatments of the day could do little to alleviate, and during the final years of his life he concealed his face in a scarf. He died in 1784 at the age of 55 and was buried in an unmarked grave at his farm in Delaware. Today the farm is called Byfield, in Rodney’s day he referred to it as Poplar Grove. Several of Rodney’s ancestors, including his father, were similarly buried in unmarked graves on the family estate.