In 2002 retired Soviet naval communications intelligence officer Vadim Orlov held a press conference to reveal a state secret. Forty years earlier he had witnessed how Vasili Arkhipov, under extreme pressure, stood up to his closest compatriots in order to prevent a nuclear war from setting inferno to the world post WW2.

Vasili Arkhipov was a fifteen year old boy living near Moscow when Hitler unleashed his invasion of the Soviet Union. Too young to serve in the military but old enough to understand the peril that his country found itself in, Arkhipov oriented himself towards a life in the Soviet military. Once he came of age he enrolled in naval officer school, and he would serve in the final days of the war in the Pacific after the Soviet Union joined the United States against Japan.

Following the defeat of German and Japan the alliance of convenience between the Soviet Union and the United States quickly dissipated. A new era of cold war emerged, in which the two superpowers flirted with annihilation in games of bluff and brinksmanship. Vasili Arkhipov would come up in this climate, trained as a consummate cold warrior, prepared to do whatever it took to prevent another tragedy like the Nazi invasion from happening to his homeland again.

Early in this contest the United States possessed a trump card in nuclear weapons. Once the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb in 1949, though, the standoff between the superpowers would center on nuclear deterrent – the principle that if the consequences of nuclear war were horrific and inevitable enough no one would ever make the decision to start one. For the next decade the East and the West engaged in a race to develop weapon systems that might keep them ahead in the deterrence race.

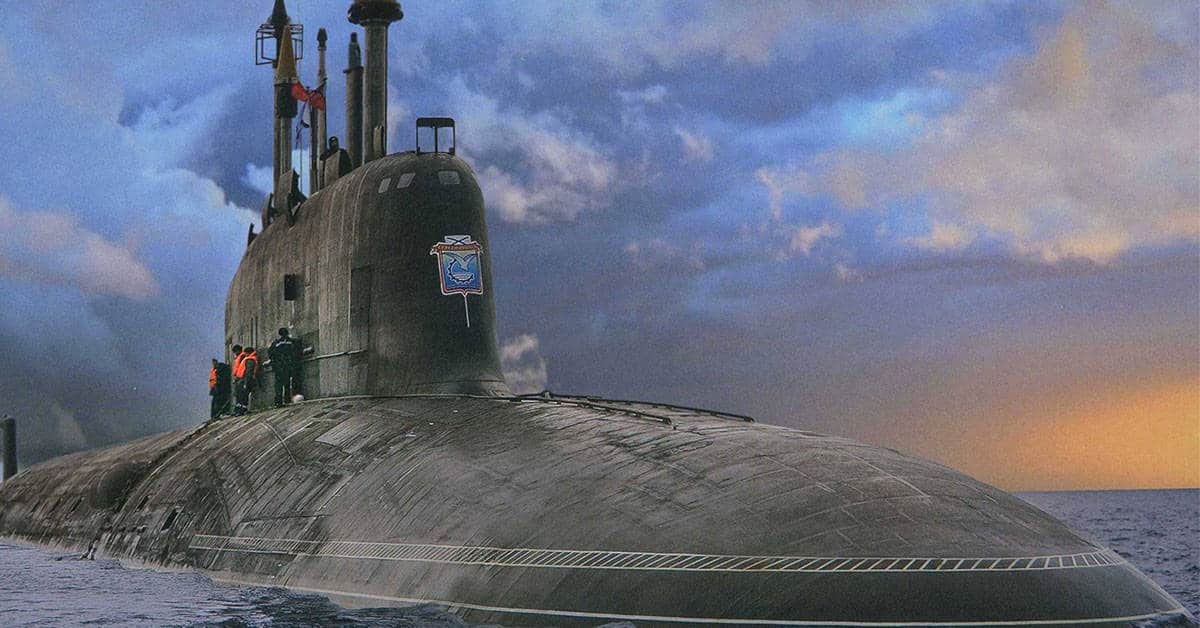

Both sides developed strategic bomber wings to deliver their nuclear arsenal, but these were relatively slow and expensive. The advent of intercontinental ballistic missiles in the 1950s overcame some of these obstacles, but the long range missiles were initially not terribly accurate and they could be destroyed on the ground. The prospect of mounting ballistic missiles on submarines seemed to overcome this vulnerability, but only if it could remain hidden from its adversary. Nuclear submarines – both propelled and armed by the energy of the atom – were engineered to fill this need. A diesel submarine had to surface to recharge its batteries with oxygen-drinking gas engines. But if a nuclear reactor were mounted on a submarine it might remain underwater for weeks without having to surface, and so retain its stealth.

The Soviets recognized the advantages of nuclear submarines as the third leg in their nuclear triad, but they had fallen woefully behind the Americans in that arena. Eager to close the gap, the Soviets rushed their first nuclear submarine, the K-19, through its production and testing process. During one trial run the onboard nuclear reactor suffered bent control rod, and in the course of another the ship took on water during a dive and only just managed to limp back home listing to the port side. Despite these setbacks, the K-19 was deemed ready for its maiden voyage in July 1961. In this first deployment of a Soviet nuclear submarine, Vasili Arkhipov would serve as the ships executive officer and deputy to Captain Nikolai Zateyev.

After only a few days at sea, a pipe supplying coolant to the K-19’s reactor cracked and the coolant pressure within the reactor plummeted. The control rods within the reactor slammed into place to halt the nuclear chain reaction driving the ship, but temperatures within the reactor continued to rise. Facing an imminent meltdown, Captain Zateyev deployed his engineers to create a new coolant system on the fly from vents and pipes cannibalized from the rest of the ship.

Though this ingenuity prevented an immediate catastrophe, the entire ship along with Arkhipov, Zateyev, and the rest of the crew had been irradiated. The K-19 would make it home, but by the time it reached port many of the men were suffering the horrific consequences of radiation poisoning. All seven of the engineers who worked on the exposes reactor, along with fifteen other crewmen, would die from radiation exposure shortly thereafter.

Twenty-six men of the K-19 received medals for containing the disaster. Though the Soviet Union had never had more confidence in the capabilities of its submariners, it lost faith in the nuclear submarine project and shelved it for a time. For Arkhipov this meant a return to diesel submarine.