Alliances have always been at the forefront of human history, and they were a feature of ancient Rome. By 60 BC, the Roman Republic was in a state of turmoil and three of its most powerful individuals set aside their differences to dominate politics for the next few years to come.

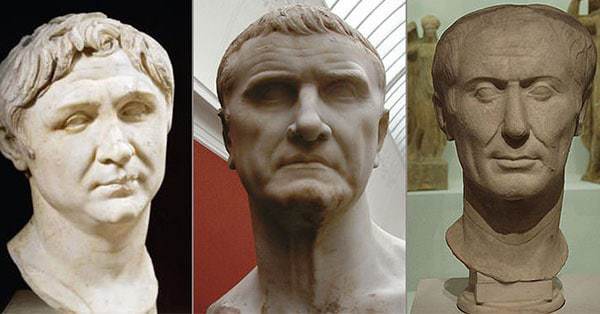

The First Triumvirate was a mutually beneficial alliance between Julius Caesar, Crassus and Pompey which was formed in 59 BC (possibly late 60 BC) and ended six years later with the death of Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae. In many ways, the term ‘triumvirate’ is misleading because it involved a number of other political figures such as Lucius Calpurnius Piso and Lucius Lucceius. Cicero was also asked to join the alliance, but he refused. Also, contemporary Romans did not use the phrase ‘triumvirate’ to describe the alliance nor did it have any official power.

1 – The Rise of the First Triumvirate Members

It was an unlikely alliance borne out of necessity and political maneuvering because the three main members did not like one another. Crassus and Pompey, in particular, had history due to Pompey’s actions in the Third Servile War in the late 70s BC. Crassus defeated Spartacus and his rebels, but Pompey swooped in at the last minute and claimed much of the glory. Both men refused to disband their armies, and in 70 BC, they became consuls. Crassus always hated Pompey for his arrogance and wanted a military command where he could lead alone and claim the glory.

Pompey gained further prestige by defeating a group of pirates that terrorized Romans on the high seas and also played a role in the defeat of Mithridates VI of Pontus. Meanwhile, Caesar returned from Spain in triumph and hoped to further his reputation in Rome. Crassus was one of the richest men in Rome; Pompey was also extremely wealthy while Caesar was deeply in debt.

Before the formation of the First Triumvirate, the politics of the Late Republic were quite clearly divided into two opposing groups; the optimates (Cicero called them ‘the good men’) and the populares (in favor of the people). The latter had the support of the commoners and promoted reforms to help landless Romans including debt relief and redistribution of land. The populares also opposed the power of the nobles in the Senate. The optimates opposed reforms and favored the nobility.

The First Triumvirate came together at a time when Rome was in complete chaos. There were rioting and street violence, clear evidence of moral decay, corrupt politicians and no real leadership. The Catiline Conspiracy of 63 BC was further proof that the Republic was in dire straits and it was only a matter of time before it fell. In fact, historians point to the Conspiracy as the starting point of the alliance.

After Cicero had discovered the plot, he ordered the execution of the plotters without trial, a measure opposed by Caesar. The optimates were accused of overstepping their power over the life and death of Roman citizens. Caesar proposed that Pompey would be given the job of restoring the temple of Jupiter, a role that belonged to a prominent optimate named Catullus. Caesar and Pompey were on good terms by now, but Crassus had mixed emotions for Pompey. Caesar recognized that it was in everyone’s best interests if they formed an alliance and made some steps towards achieving this goal soon after.

In 60 BC, Caesar did not seek a triumph for his achievements in Spain and sought the office of consul for 59 BC. However, he faced stiff opposition from the optimate Senators, so he decided to approach Pompey with a proposition. Caesar and Crassus were already allies at this point, and Caesar managed to patch things up between the two enemies. Therefore, the First Triumvirate was formed with mutual benefit for the three main members. Pompey wanted land for his veterans; Caesar wanted to become Consul and further his political ambitions while Crassus wanted the opportunity to command an army.