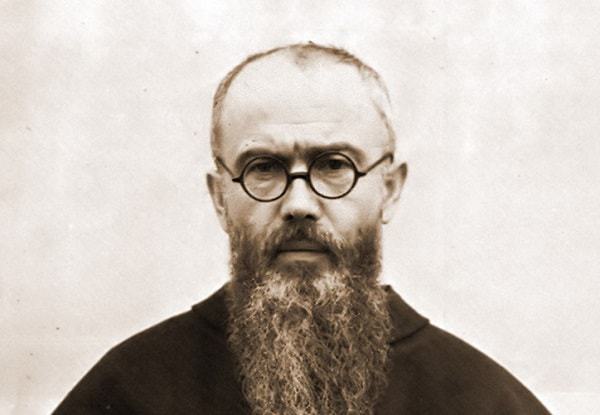

Maximilian Maria Kolbe was a Polish Franciscan friar born in 1894. In 1941 He was sent to Auschwitz concentration camp for Anti-Nazi activities. Here, Kolbe showed tremendous courage and faith in the face of adversity, the culmination of which was to take the place of a complete stranger who was sentenced to die.

Kolbe’s sacrifice led to him being declared a Catholic saint. Yet he is also contentious figure to some groups, with many Jews considering him to be anti-Semitic. Is this attitude justified? And what motivated Kolbe to make such a sacrifice?

Early Life

Maximilian Kolbe was born on January 8, 1894, the second son of a weaver and a midwife. In 1906, Kolbe had a vision of the Virgin Mary. The vision told Kolbe he could persevere in purity- or become a martyr. Kolbe later said he accepted both.

The vision also convinced Kolbe of his vocation and a lifelong devotion to the Virgin. In 1907, he and his elder brother Francis joined the Franciscan order. In 1914, Kolbe was fully ordained as a priest. In 1915, he earned a doctorate in philosophy from the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome.

Soon afterward graduating, Kolbe organized the Militia Immaculata, an organization which worked on the conversion of sinners and enemies of the Catholic Church- such as freemasons.

In 1927, Kolbe founded a new Franciscan monastery at Niepokalanow, near Warsaw. The friary became a religious publishing center, printing 11 periodicals, and a daily newspaper. After a period of years on missions in Japan and India, Kolbe returned to Niepokalanow in 1936 and in 1938 started up radio Niepokalanow.

The German Invasion

After the German invasion, most of the friars left Niepokalanow. But Kolbe stayed on, opening the monastery as a hospital. Polish refugees began to rush to it for sanctuary.

The invading Germans initially arrested Kolbe. As he had German ancestry, they tried to get him to sign the Deutsche Volksliste, which would have granted him the same rights of German citizens. Kolbe refused. Never the less, he was released and he returned to the monastery where he and the remaining friars continued to nurse their patients- and provide shelter for 2000 Jews they managed to hide from the Nazis.

But humanitarian aid was not all the friars dedicated themselves to. The monastery was given permission to continue printing its religious works. But it also began to publish anti-Nazi propaganda. And so, on the 17th of February 1941, Niepokalanow monastery was seized and shut down by the German authorities. Kolbe and four other friars were arrested by the Gestapo and taken to the Pawiak Prison.