Parachute drops in the predawn hours. Increased activity by the French Resistance, coordinated with British, American, and Canadian commandos. A great fleet pounded German positions on the shores of France, followed by landing craft crawling towards the hostile beaches. Waves of attack aircraft bombarded German reserves and artillery positions. This sounds like the description of the iconic invasion of Normandy, but this is actually a little known event. This invasion took place on August 15, 1944. The invasion was neither as large nor as well known as the other great French invasion of World War II, but it was an allied invasion of France, two months after Operation Overlord placed allied troops in Normandy. It was called Operation Dragoon, and the Allies landed in Southern France, in Provence. The British participated in it though they officially opposed the plan.

Churchill argued against the plan directly to Roosevelt, arguing that the troops and materiel involved would be put to better use in Normandy or Italy. He believed that an invasion in Southern Europe would be better placed in the Balkans, where it could disrupt German oil supplies (and provide stronger British influence in Eastern Europe after the war. Dragoon was originally called Anvil, scheduled to occur at the same time as Overlord, but logistics made that unfeasible. By August, the desirability of seizing the French Mediterranean ports of Marseille and Toulon made Dragoon a necessity, as the Northern ports were unable to provide enough support.

Here are ten facts about Operation Dragoon, the other invasion of France by the Allies during World War Two.

Preparing for the Invasion

Despite Churchill’s continuing protests, in which he was supported by Field Marshal Montgomery, American commander Dwight Eisenhower recognized the paralyzing effect the lack of northern ports was having on the Allied troops in northern France. The Americans captured Cherbourg in late June, but the port facilities were destroyed. German forces in the south of France were for the most part garrison troops, with some armor support, but Allied pressure on the Germans in Normandy and Italy, as well as the attacking Russians, prevented the German High Command from diverting much strength to the Mediterranean, though they expected another invasion there.

The casualties suffered by the Allies at Normandy and Anzio provided lessons learned and they were applied to Operation Dragoon. The beaches selected were not dominated by high ground, and paratroops were dropped in areas to secure the inland high ground, denying it to Germans retreating from the beaches, and to reinforcing troops. Bridges were bombed to prevent German reinforcements from arriving at critical points. Most of the German units in southern France weren’t German at all, but comprised of volunteers and conscripts from some of the Soviet Socialist Republics. The units had lost most of their heavy equipment to replenish fighting units on the Eastern and Western Fronts.

The German High Command was aware that the defense of southern France was virtually impossible against a determined attack, and plans were already being made to withdraw to a new defensive position when Operation Valkyrie was executed. The attempt to kill Hitler and the ensuing purge of Wehrmacht officers made proposing any form of retreat dangerous to the proposer. The coastline was protected by numerous heavy gun emplacements, with many of the guns stripped from French naval vessels after they were scuttled at Toulon. The Vichy government installed the guns and after the Germans occupied all of France they strengthened the emplacements.

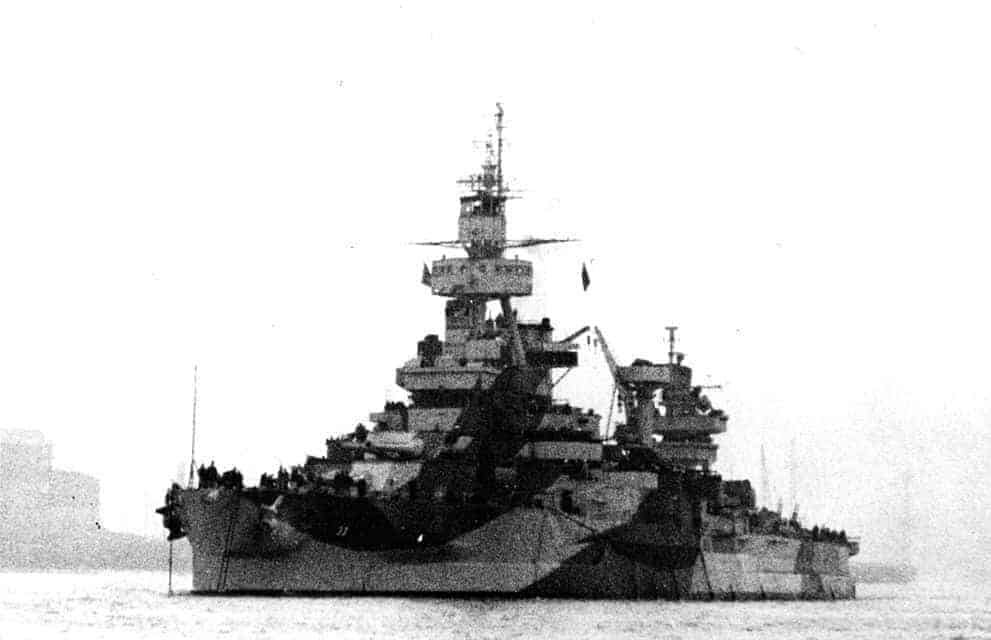

To counter the shore batteries the Allied invasion fleet included five battleships (USS Nevada, Texas, Arkansas; HMS Ramillies, and the French battleship Lorraine) along with a force of twenty cruisers. A force of nine escort carriers and their destroyer escorts was also assigned to Dragoon, though the majority of the air support for the invasion came from the islands of Sardinia and Corsica. Strategic bombing of targets and French resistance operations coordinated by OSS and SOE members began in July, 1944. German reprisals against captured Resistance members were swift and harsh.

As more and more German units were removed and sent to the front in the north, German strength to defend against the impending invasion dropped to less than 300,000 men, in eleven divisions, and just one panzer division, which was itself under strength. Despite the known weakness of the German defenses Churchill and Montgomery continued to argue against an invasion of the south. Less than one week before the planned invasion date Churchill suggested transferring the entire operation to the coast of Brittany in northern France. Montgomery wanted the forces committed to Dragoon to be assigned to him as part of the planning for Operation Market Garden.