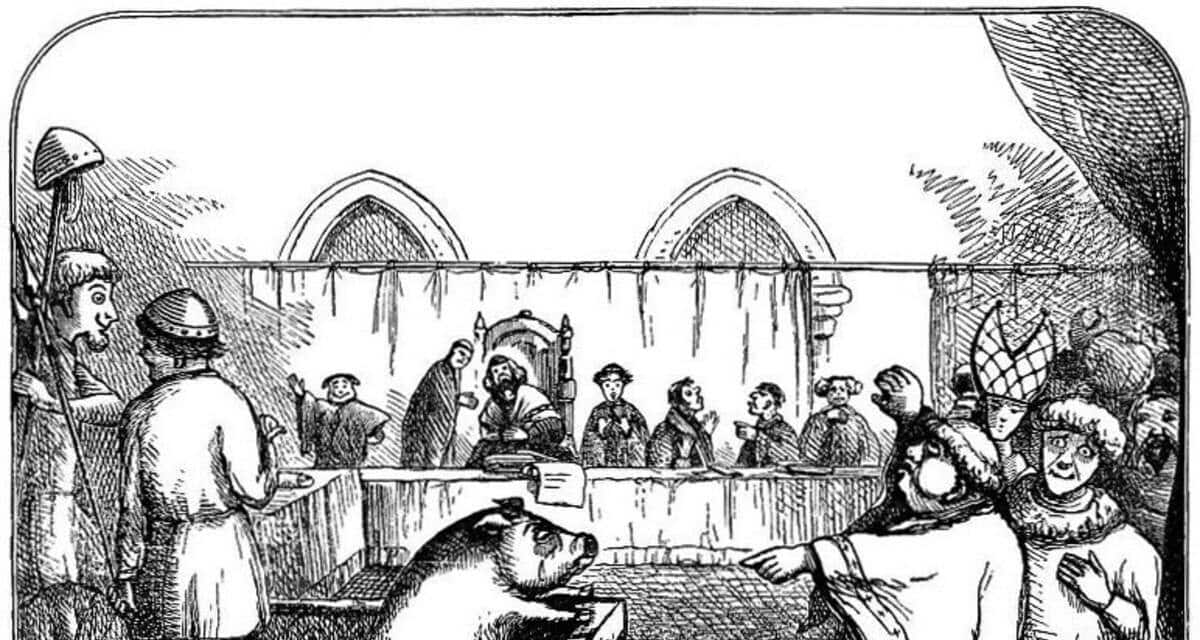

Medieval history is full of many fascinating – and sometimes strange – traditions and facts. Take animal trials. In Middle Ages Europe, animals could be charged for a variety of crimes, and be tried in a court of law just like humans. If tried in ecclesiastical courts, the animals even had lawyers appointed to act as their public defenders. They were afforded no legal representation if tried in secular courts, but then again, neither were human defendants. And just like humans, if convicted, the authorities could go medieval on the animals with cruel punishments. Below are twenty five things about those and other fascinating but lesser known medieval facts.

When Animals Faced Criminal Charges

In medieval Europe, animals that misbehaved could be criminally tried in court. For example, in 1457, a sow in Savigny, France, with six piglets in tow, attacked and killed a five-year-old. Nowadays, the sow’s owner might face criminal charges for negligence, but medieval Europeans had different notions of law and justice. The authorities in Savigny charged the sow with murder, and brought charges against the piglets as accomplices. A lawyer was appointed to defend the accused, and after testimony was heard, a judge found the porcine guilty. In accordance with local custom, he sentenced her to be hanged to death by her hind legs. If it was any relief to the sow, her execution was not as painful as that of another pig convicted of homicide in Falaise, Normandy, in 1386. It was sentenced not only to hang, but to also be maimed in the head and forelegs before hanging.

The piglets did not share their mother’s fate. Although they had been found covered in blood, their participation in the murder was not proven, so they were acquitted. To criminally try an animal might strike us today as ludicrous, because we know that animals lack the moral agency necessary to make them culpable for crimes. People thought differently in medieval Europe, however. All involved, judges, lawyers, bailiffs, and hangmen in case the animal was found guilty, took the proceedings quite seriously. The Savigny sow had been imprisoned pending the trial, and the jailer charged the same daily rate for the pig’s board as that of human prisoners. The court hired a professional hangman to carry out the sentence, and he charged the same fees as those charged for the execution of a human.