Citizen Louis Capet rose early on a cold morning in January of 1793. At 5 AM, he dressed with the help of his valet and went to mass. He received communion, and at 7 he stepped aside for a few quiet words with the priest. There was a small matter of what to do with the few possessions he had left. First, his wedding ring was to go to his wife, Marie Antoinette. Second, his royal seal was to go to his young son. For you see, Citizen Capet had another name: Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre. And he had a date that morning with the most feared woman in France, Madame La Guillotine.

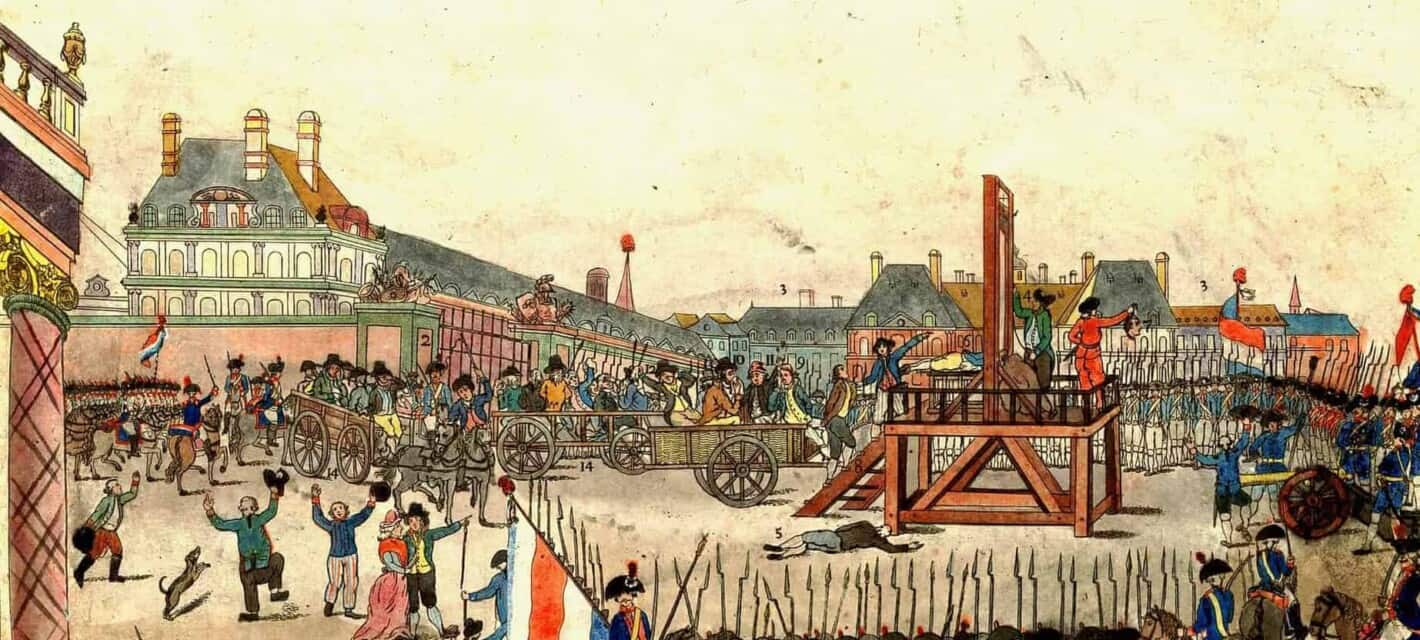

Over 1000 pounds of wood and steel and with an 88-pound blade, the guillotine was a terrifying instrument of execution. It consisted of two upright posts, between which hung a razor-sharp blade. Victims would be laid face down on a bench between the posts as their heads were secured by a wooden board with a circular hole that fastened around their neck. The executioner would then release a rope, dropping the blade. The heavily-weighted blade fell, guided by grooves in the posts, and severed the victim’s head in a fraction of a second.

It sounds barbaric, but the guillotine was actually meant to make executions more humane. And compared to some of the earlier methods of execution used in France, it did. First, there was “breaking on the wheel.” It was a particularly gruesome way to die, with the condemned being tied to a circular wheel as the executioner methodically smashed their bones with a hammer or iron bar. And if not sentenced to the wheel, those condemned to die could look forward to being hanged, burned alive, boiled alive, or dismembered depending on their crime.

When you consider the alternatives, simply being beheaded was seen as getting off easy. Of course, that had its own risks. It wasn’t uncommon for a drunk or inexperienced executioner to require four or five strokes with an ax or sword to decapitate someone. It was considered smart, if not even just simple courtesy, for the family of the condemned to bribe the executioner to make sure that his blade was sharp before the beheading. And in France, as in many countries in Europe, beheading was generally seen as a punishment reserved for the rich.

But in 1789, driven by hunger and new ideas about things like “equality” and “personal liberty”, the French rose up in revolt against the king. After several major defeats, Louis XVI reluctantly agreed to respect the will of a new “National Assembly” that could draft laws and check his absolute power. In October, Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin presented a proposal to this assembly. In line with the new spirit of equality, everyone in France should be entitled to a beheading if they were sentenced to die. The best way to do this, he suggested, would be by machine. No drunk executioners. No dull blades. No bribes. No wavering. Just steady, pitiless, instant death.