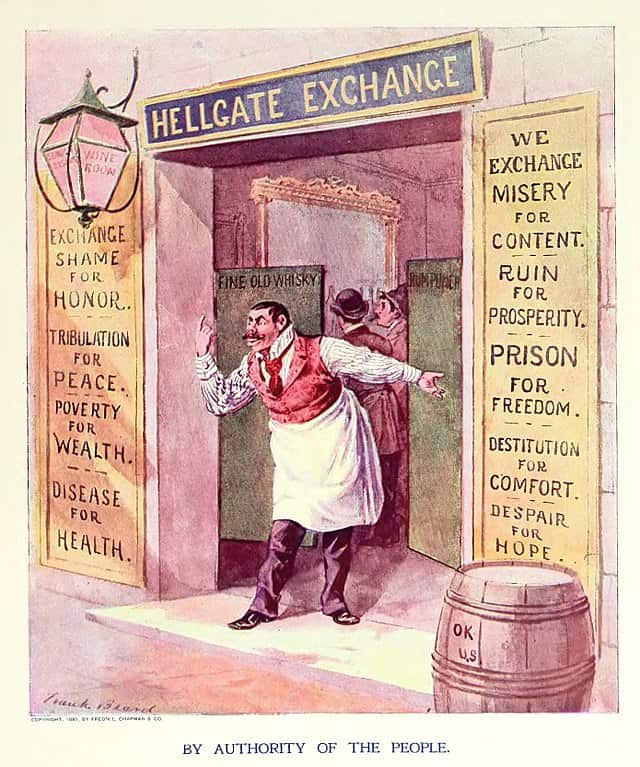

The social movement against any use of alcohol other than for medicine began in the United Kingdom, spreading to the United States as the temperance movement. It arose during a hard drinking age when the use of alcohol was fully accepted by the upper classes and the bourgeoisie, both of which came to condemn drunkenness among the poor and lower class. Both beer and wine were considered healthful beverages, but a growing backlash against distilled beverages began to develop in England, especially one drink believed to be the cause of all of the troubles of London’s poor – gin.

The gin craze in London, which lasted about forty years when gin could be distilled by anyone and their product was untaxed, produced cheap liquor and the inevitable backlash. Those of upper society, consuming wines and brandies, found the gin craze to be the ruination of the British working class. Temperance societies, which in the 1720s included coffee as an intoxicating liquor and coffee houses as dens of iniquity, began to preach against the ravages of drink. In the American colonies, gin was not the problem it was in London, and rum became the product of the demons of hell. The temperance movement in America predated its independence.

Here are ten milestones in the evolution of the temperance movement which led to prohibition in the United States.

The early temperance movement in the United States

In the beginning, the temperance movement in the United States was church based, with small groups forming in congregations, for the most part men who mutually pledged to each other to practice moderation when consuming alcoholic beverages. At the time the complete exclusion of alcohol was unwise, particularly in cities and larger towns, where the water supply was often questionable as to its quality. Locally brewed beer, which was the only kind of beer there was, and wine were considered healthful beverages. Distilled spirits, which in America consisted of brandy and rum, and to a lesser extent whiskey, were the beverages focused upon by the temperance groups.

In the developing western areas, farmers found it was easier to move their crops to market – particularly corn, rye, and barley – in liquid form, and whiskey distilling grew. Temperance groups, focused on moderation rather than abstinence, began to form outside of the churches, though often with their support. Wesleyan, Calvinist, and Methodist congregations were all in theological agreement with the practice of moderation. Following the War of 1812 there began in the United States a religious and moral movement called the Second Great Awakening, and during the period the issues of abolitionism, women’s suffrage, and temperance became linked.

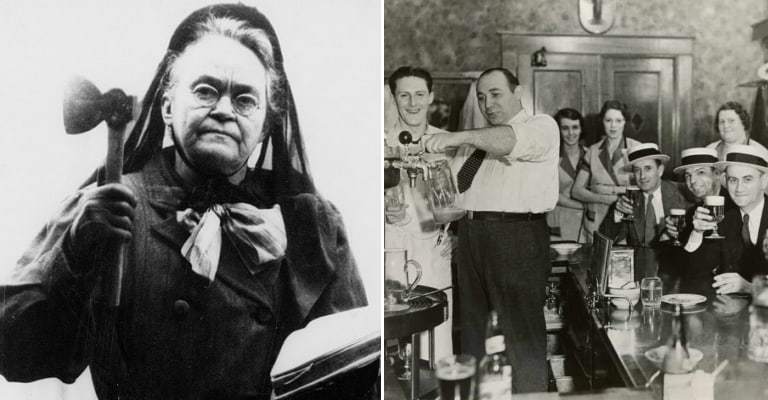

In 1826, at the height of the Second Great Awakening, the first calls on a national level for the prohibition of the sale of alcoholic beverages were heard. The American Temperance Society was formed, and driven by religious fervor, expanded rapidly to include over 1 million members within a decade, across several states. The Second Great Awakening also saw the birth of Mormonism and the creation of Seventh-Day Adventism, both of which called for abstinence. The consumption of alcohol, in the eyes of the most fevered of the reformers, became the great national shame, its production and sale the great national sin.

In the United Kingdom a similar movement developed, driven largely by Presbyterian ministers and congregations, and the movement, as in America, was soon linked to women’s suffrage. A healthy exchange of correspondence between the movements across the Atlantic led to the development of temperance newspapers, magazines, and propaganda. By 1831, Presbyterian churches on both sides of the Atlantic required a pledge of total abstinence, signed in the presence of the congregation, before salvation could be received. Temperance became irretrievably linked to total abstinence and the prohibition of alcohol.

The Mormon Word of Wisdom is a health code written while the Mormons were living in the vicinity of Kirtland, Ohio. The Word of Wisdom includes total abstinence from alcohol. At the time it was written Joseph Smith was a consumer of alcohol, a practice which he continued following the move to Nauvoo, Illinois, and Smith did not counsel total abstinence. The Word of Wisdom was viewed as advice, rather than law, which it became in 1921. Later apologists attempted to portray Smith as a teetotaler, refusing alcohol even as an anesthetic, but contemporary reports document his social drinking of beer and wine, as well as other “violations” of the Word of Wisdom.