Life was hard in the smoggy climes of Victorian London. Thieves and thugs hid amongst soot-blackened slums, malevolently eyeing the lords and ladies negotiating the piles of horse dung and puddles strewing the road. The poor shivered in darkened alleys, their stomachs rumbling a symphony in praise of the joys of living without a welfare state. Children hunched like old men, carrying brushes to clear yet another chimney belonging to yet another rich, apathetic family. Such unfortunates were kept in check by abject poverty and Draconian laws. In this miserable time, bloodsports were amongst the most popular forms of entertainment.

Chief amongst these dreadful sports was dog-fighting. Dog-fighting is the pitting of two or more dogs against each other in an enclosure in which they either fight to the death or until one is unable to continue due to the seriousness of its injuries. In the nineteenth century, the sport was popular amongst the hoi-polloi and riff-raff alike, as vast sums of money could be won by betting on the outcome of the fights. Into this vile and unforgiving ‘sport’ came the diminutive figure of Jacco Macacco, an ape whose fighting record is alleged to have brought fifteen victories.

According to William Pitt Lennox, an army officer and sporting writer, Jacco was brought by boat from Africa to Portsmouth, where he was immediately pitted against some provincial curs, before being taken to the wider audience of London (in a manner resembling theatre directors trawling through local theaters to pinch the best talent, notes Lennox). He won a fearsome reputation as a fighter, but turned on his own master, and was sold to the proprietor of the Westminster Pit, one Charles Aistrop. Aistrop has a differing, more entertaining, account of Jacco’s origin: an exotic pet gone very bad indeed.

Aistrop claimed that Jacco had turned on his first owner, a sailor, over a saucer of milk, lacerating three of the man’s fingers. The sailor sold Jacco to Carter, a silversmith from Hoxton, who soon wearied of the ape’s ceaseless attempts to attack him. For Jacco, the erstwhile-pet, had turned extremely savage, and Carter had to buy a thick sheet of iron to protect himself from attack when he approached the creature. Carter took Jacco to a field and set a dog on him, which the ape killed with little difficulty, before swiftly dispatching two further would-be canine assailants.

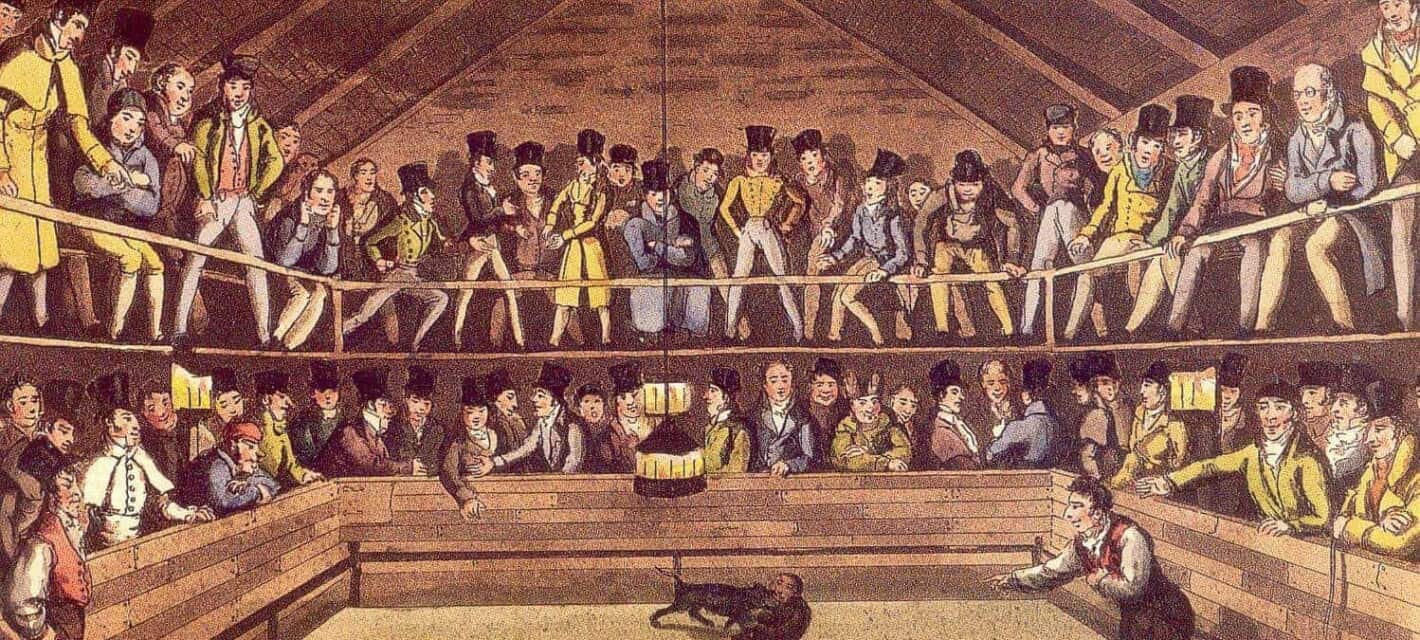

Sensing a use for Jacco’s uncontrollable aggression, Carter pitted him against fighting dogs in local dog-fighting pits, most of which he killed within minutes by tearing out their throats. Jacco’s fame saw him sold to Charles Aistrop, after which his fame grew exponentially. The Westminster Ring Jacco now graced was amongst the biggest in London, and tales of his exploits were celebrated not just in gin-soaked taverns but reported in newspapers. Soon, owners of the most ferocious dogs in London wanted to pit their pets’ wits against the great Jacco Macacco, for with celebrity came a fortune in betting slips.