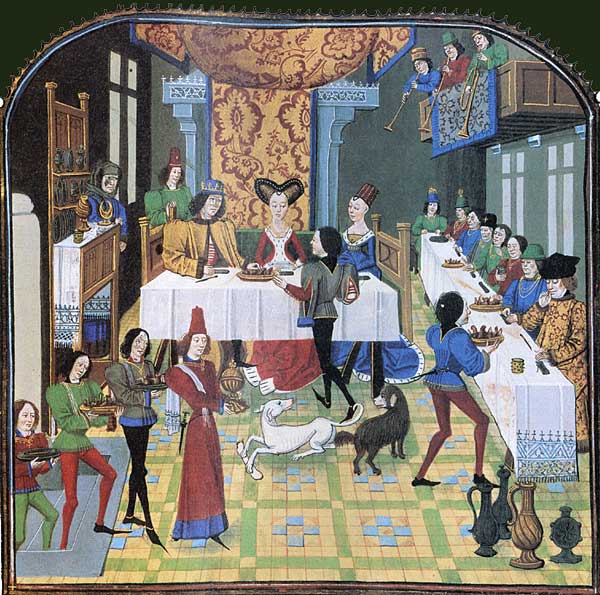

In medieval times a proper feast was an extravagant affair, with immoderate servings of food and beverages, entertainment, dancing, and minimal place settings. Unlike the formal table settings prevalent today, there were no forks, and guests ate with a knife and a spoon, which they were expected to bring to the table themselves. If they wanted to consume the proffered beverages, they were expected to bring their own drinking vessel as well. Most were of wood, which prevented breakage when things got out of hand, as it often did.

A medieval feast varied depending on the nation and the regions of some nations. Southern French customs and cuisine had more in common with Spain than with those of Paris. Brittany was closer to the customs of the British across the Channel than it was of Paris. One thing all large medieval feasts had in common was the large number of servants required to properly host one, and to care for the guests conveyances as they dined and drank, which often went on for days at a time. Compliance with the Church calendar was another consideration when planning menus, as was of course the season of the year.

Here are ten customs of the medieval age which should be followed when planning a proper medieval feast.

Treating and serving the guests

When the Lord of the Manor determined to host a feast invitations were of course sent out, delivered by servants, to those it pleased him to beckon. These were not necessarily all of the higher classes. Tenants of his lordship’s estates were often welcomed to the Great House, but seated according to their lower class standing. A guest’s rank in class could be ascertained by the distance from which they were seated from his Lordship’s table, or in the case of a single table (which was rare) the distance from his host’s chair.

The fork had not yet made its appearance, and the only dining utensils used at table were the knife and spoon. They were not found at the table, but brought to the table by the guest, along with a drinking vessel. Spoons were nearly always made of wood, as were the drinking vessels, although his Lordship and favored guests sometimes drank from pewter mugs, or even vessels made of gold or silver. Knives were used to both cut some foods and to convey them to the mouth, thus they had to be both sharp and carefully used.

His Lordship and those guests who were in his opinion worthy to sit at his table were placed in a position where they were in clear view during the dining, usually on a raised dais. At least one, and often two or three tables were arranged perpendicular to his elevated seat, with guests sitting on only one side of the tables, the other remaining open for ease of access by the servants. The guests were arranged in groups called messes, and each mess would share from some of the foods brought to table, such as one roast per mess, or one beef pie for the group.

The number of servants was of necessity greater than the number of guests, as all diners were required to wait until his Lordship took his first bite or sip of each course before starting on their own. In like manner, no person took their seat at the table until his Lordship was comfortably seated at his place. If he rose during the course of the meal, unless he ordered otherwise, all the diners were expected to rise as well. His Lordship was of course the first served, and since he likely had no desire to see whatever had been placed before him grow cold, he needed sufficient servants to ensure that all his guests were served quickly. It was considered improper for anyone, including the Lord of the Manor, to begin eating before all were served.

In medieval feast was not divided into courses in the same manner as formal dining today, with an appetizer course, a soup course, and so on. There were different courses served and a lull between them, during which the table was prepared for the succeeding course and the guests were entertained with music, or by dancers which were more acrobats than ballet performers. A feast in France might have seven or more courses, each consisting of several dishes presented to each of the messes at table. In Britain there were more likely to be three.