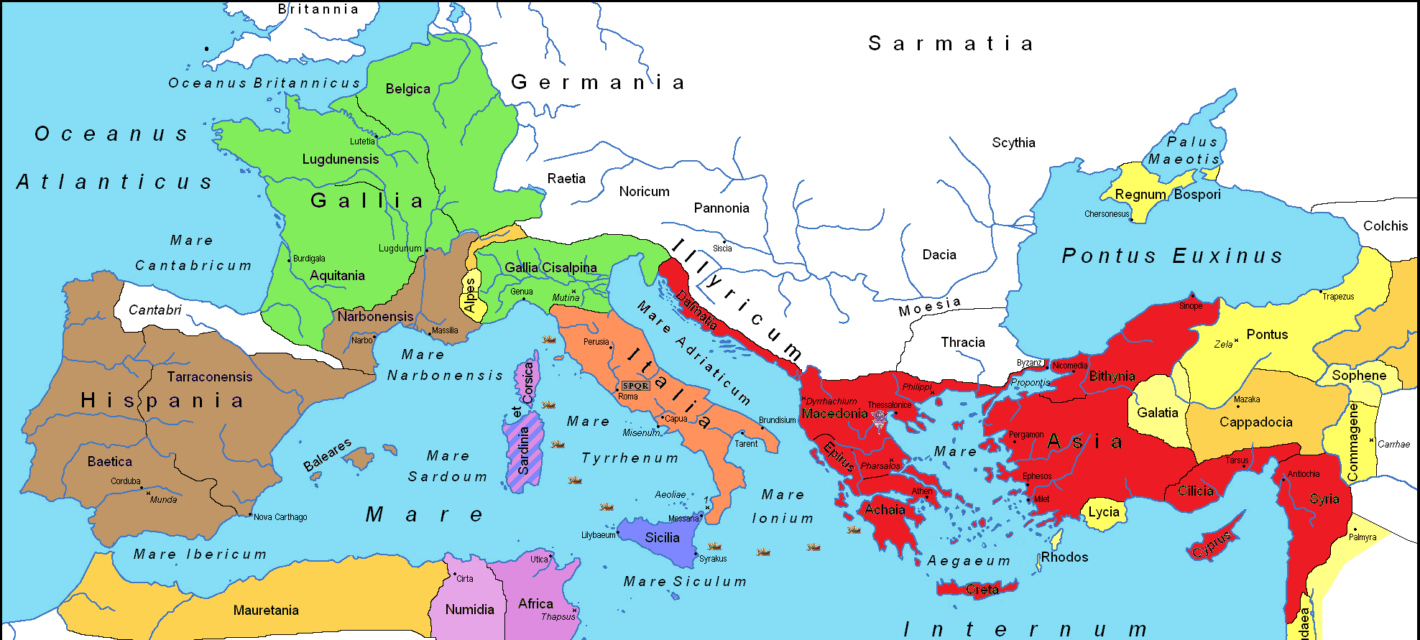

The Roman Republic is believed to have been formed in 509 BC, and the first two consuls were Lucius Collatinus and Lucius Brutus. For the first two centuries of its existence, it expanded via alliance and conquest and controlled the Italian peninsula. Historians have tried to suggest that Rome’s expansion was not just due to a thirst for conquest.

Regardless of the reasons, Rome created one of the world’s great empires, but it didn’t enjoy unbridled success for centuries. As you will see below, it suffered its share of humiliations, but instead of being beaten down by military losses, Rome learned from its mistakes and its tactics evolved until its might eventually surpassed that of its rivals. In this article, I look at six crucial battles in the history of the Roman Republic. Some of them were complete failures, but these defeats helped shape Rome and allowed it to grow and prosper while its rivals fell. Actium is not included as I will be writing about that battle in detail at a later date.

1 – Battle of Allia River (390 BC)

There is a little confusion over the date of this battle. The traditional date is 390 BC, but Greek historian Polybius dates the Battle of Allia River in 387 or 386 BC. The fight took place between a number of Gallic tribes, led by Brennus (also the leader of the Senones), and the city-state of Rome, led by Quintus Sulpicius.

From 1000 BC onwards, Gallic tribes had gradually expanded from Central Europe into the West where they were tried to settle on the lush Mediterranean lands. They moved into the northern Italian plain and by 400 BC, they began to take land by force. In 391 BC, Brennus led his men into Etruria and laid siege to the town of Clusium. The town asked Rome for help, and the city sent the Fabii to Clusium to act as envoys. One of them murdered a Gallic chieftain, and when Rome refused to hand over the Fabii, the Gallic chiefs declared war.

The Romans believed they could easily defeat a group of barbarians and met the enemy at Allia River, about 11 miles from the city of Rome. As is normally the case with ancient battles, the numbers attributed to each army varies. The Romans apparently had anywhere from 15,000 to 24,000 men while the Gallic warriors had an army of 30,000 to 70,000. Although the Gauls only consisted of light infantry while the Romans had at least 6,000 heavy infantry, Brennus cleverly used his numerical advantage to extend the front of his army beyond that of the Romans.

This forced the Romans to take men from the center to counteract the lengthy Gallic lines. However, lack of men ensured their lines became extremely thin. Brennus used his best men to attack the inexperienced Roman reserves on his left flank, and the Gauls overpowered their adversaries. The rest of the Roman army started to get nervous, and this turned into full-on panic when the main Gallic army launched its attack. Brennus and his men quickly steamed through the Roman phalanx and achieved an extremely easy victory. Numerous retreating Romans drowned in the River Tiber. Up to two-thirds of the Roman army were killed or captured at Allia.

Within a few days, the Gauls marched to Rome and sacked the city. Some Romans held out on Capitoline Hill and eventually, with disease causing damage to the Gallic ranks, Brennus withdrew after receiving a huge ransom. The entire saga was a total humiliation for the Romans, and it had a profound impact on its military. A variety of reforms were implemented during the 4th Century BC Samnite Wars. For example, the phalanx was replaced by a more mobile unit while the famous scutum replaced the round shield. While Rome was to suffer more defeats, the loss at Allia River paved the way for the growth of the Republic and eventually, the Empire.