The death of Pope Pius XI in February 1939 marked the beginning of an unprecedented archaeological treasure hunt. The deceased pontiff wished to be buried next to the tomb of Pope Pius X, the mentor who had appointed him head of the Vatican library and close to the Tomb of St Peter. As Pius XI was the first Pope to head the newly formed Vatican City state, his tomb needed to be unique. So, on the orders of the new pope, Pius XII, work began to clear space beneath the floor of St Peter’s Basilica to make way for the new tomb.

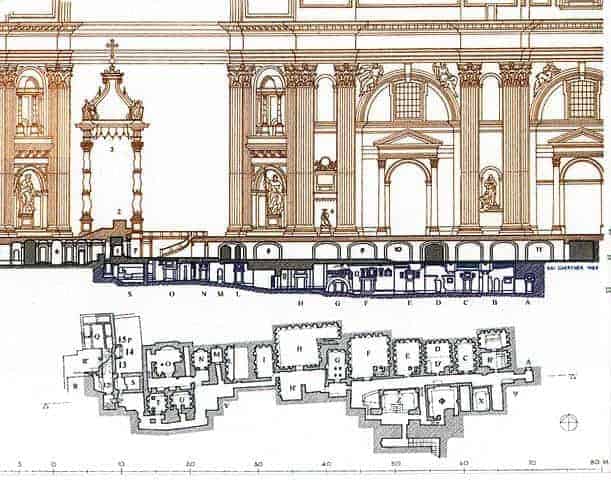

As they began to clear the ground, the workman discovered that there was more to the foundations of St Peter’s than expected. For just five meters beneath the Basilica floor, past the remains of the Emperor Constantine’s original Church, they found an ancient Roman city of the dead; a necropolis that housed the remains of both pagans and Christians. Vatican officials quickly realized that somewhere in that necropolis, was the last resting place of the First Pope. So, Pius XII authorized unprecedented excavations beneath the Basilica. Over the next ten years, the necropolis gradually revealed itself and its secrets to the world. But was it the last resting place of the first Pope?

The History of Mons Vaticanus

The Vatican Hill was not one of the Seven Hills of Rome. The Mons Vaticanus as it was known, lay outside the ancient city limits, facing Rome from across the River Tiber. The hill’s name was Etruscan in origin. Some attributed it to the Vates, the Etruscan tribe who formerly lived there and built a settlement, Vaticum. Others believe the name derived from the Etruscan god of prophecy, Vaticanus whose temple was also on the hill. Here, observing the flights of birds and lightning strikes helped gauge divine will.

For the Romans, however, the hill was the perfect place for other activities not appropriate in the city. It was the site of the temple of Cybele and Attis, the gods of a Greek mystery cult brought to Rome in the late republic. One of the rites of the religion was the taurobolium, which bathed cult adherents in the blood of a bull. The Roman elite initially suspected the cult. However, it was still in use during the fourth century, after Christianity became a legal religion.

By this time, the Vatican Hill had another significance. It was now a place of martyrdom. The Circus of Caligula/Nero occupied Gardens of Agrippina on the Vatican hill, and it was here in 65AD, that the Emperor Nero the notorious executions of suspected Christians. One of those Christians was St Peter, Christ’s apostle and the first Pope of the Church in Rome. Peter was killed sometime between 64-67AD after he “came to Rome and was crucified with his head downwards,” according to Eusebius, a historian from Constantine’s era, who was drawing on earlier references from the third-century theologian Origen and a letter written by Clement, Bishop of Rome in 96AD.

An Egyptian obelisk, which marked the spina of the circus, is all that survives of it today. This relic now adorns St Peter’s square- the original site of the Circus. However, the Circus was long gone by the Christian era. It had been demolished to allow for the expansion of the cemetery that ran along the Via Cornelia at the base of the hill. Roman law forbade the burial of the dead within the city limits. So it was customary for citizens to bury their departed relatives in tombs that lined the roads leading out of Rome.

The cemetery of the via Cornelia gradually began to spread away from the road and by the time of the Christian era covered the whole of its southern slope. It was still in use by pagans and Christians alike by the time Emperor Constantine decided to build his Basilica to commemorate St Peter in 330AD.

However, the necropolis was in the way. Aside from the fact that all graves were protected by Roman law and could not be destroyed, Constantine faced the additional problem that somewhere amongst them was the tomb of St Peter. It would not do to obliterate the last resting place of one of the founders of his newly adopted religion. So the emperor came up with an ingenious solution.