Escaping prisoners of war enduring heart in the throat tension as they first slip away from their captors and then use guile and cunning to elude pursuit, eventually finding their way to safety, have been dramatized in novel and film to the point of becoming cliché. In reality many of the most heart pounding escapes have been forgotten. Allied prisoners of war completed many escapes which have never merited the dramatic license of Hollywood, yet contain all of the drama and climactic scenes of those created for the screen.

World War II saw many attempts at escape which were aided and abetted by organizations which were created for the purpose. Allied organizations manufactured and provided escape aids through the assistance of relief packages distributed by international aid organizations created for the purpose. Maps, money, compasses, and other items of use to escaping prisoners were covertly distributed to POWs. Underground groups developed safe house and escape routes to help POWs on the run from their captors regain their freedom. But above all it required the courage, planning, and determination of the escapee to endure the hardships and dangers of life as a desperately sought for fugitive to ensure a successful escape from captivity.

The allied command considered the temporary freedom from captivity to be a successful escape since it forced the enemy to expend manpower to recapture a prisoner. But to the POW a successful escape was the safe return to home and loved ones. By their standard, here are some successful escapes from captivity by POWs during World War II.

Henri Giraud. Konigstein Castle

During the First World War French captain Henri Giraud was seriously wounded in battle and abandoned by his comrades on the field, leading to his capture by the Germans. After partially recovering from his wounds in a POW camp he escaped and made his way towards Allied lines disguising himself as a laborer for the circus, presenting himself to inquisitive authorities as being not quite right in the head.

Eventually he made contact with British nurse Edith Cavell (who helped over 200 prisoners escape during the war before being shot) who helped Giraud to freedom. Having thus acquired what should have been enough adventures for a lifetime, Giraud remained in the French Army between the wars and by the time World War II began was a senior commander of French troops on the Western Front.

During the Battle of France Giraud was again captured by German troops after attempting to block the initial thrust of the German Army through the Ardennes Forest in Belgium. Prior to his capture Giraud had ordered the execution by firing squad of two German soldiers who had been captured wearing civilian clothes by troops under his command. The Germans tried him for this act, but he was acquitted and sent to a high security POW facility for senior officers, a mountaintop stronghold near Dresden, Germany called Konigstein Castle.

For the next two years Giraud occupied his time by learning to speak German, obtaining maps of the area, and preparing a homemade rope made from twisted bedding, old clothes, bits of rope, and copper wire. He informed friends and family of his plans through coded messages in his letters home, and in 1942 he descended the nearly sheer cliff below the castle using his rope.

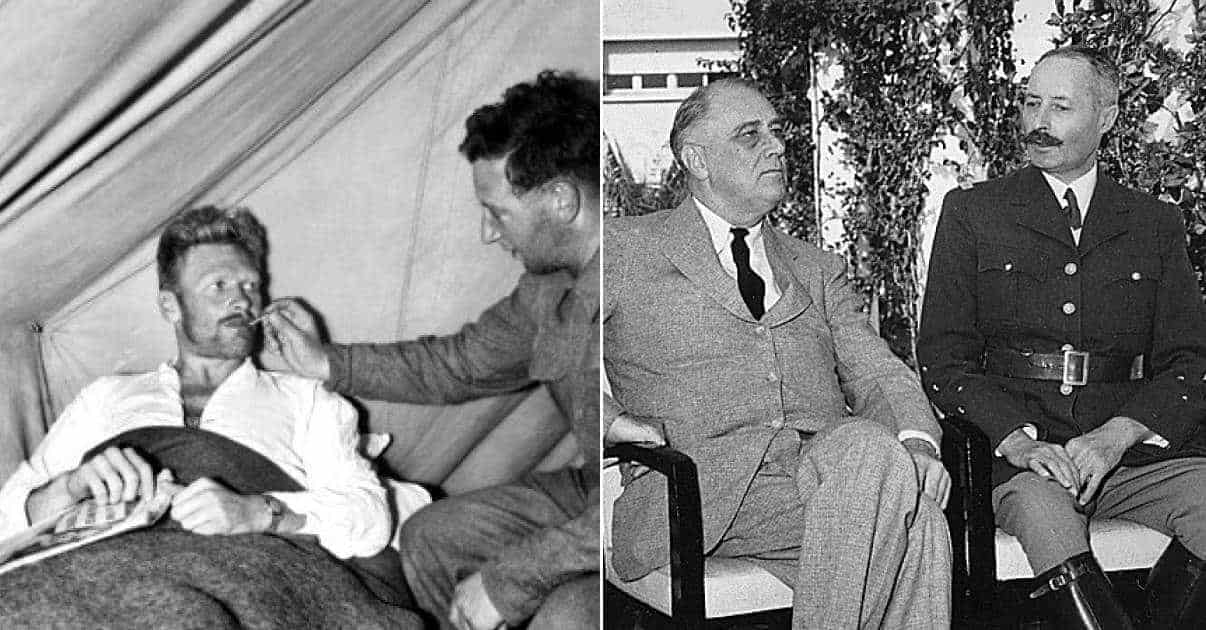

The British Special Operations Executive had been informed of his plans and had an agent present in nearby Schandau to assist the French general. Through the assistance of the SOE and the French Resistance Giraud reached Switzerland and eventually Vichy France, where the collaborationist government rejected German demands that he be returned to prison, aware of the attitude of the French populace towards his heroic actions. Giraud remained a hero of France for the remainder of his life, despite the jealousy and suspicion of deGaulle, whom he joined at the Casablanca Conference with Churchill and FDR. Giraud eventually wrote a book entitled Mes Evasions (My Escapes) in 1946. He died in France in 1949.