Nativism – the promotion of the rights of native inhabitants over those of immigrants – has been a longstanding component of American political discourse since the establishment of the United States in the late-18th century. Ironically overlooking the rights of Native Americans, white citizens of the United States have habitually and recurrently opposed the expansion of their societies into more culturally diverse units.

A persistent aspect of American politics during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the reappearance of nativist tendencies in recent years carries significant rhetorical and ideological parallels to these earlier episodes. Lending credence to the affirmation that “‘those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it”, it is important to appropriately understand these historical and long-running cultural concerns to better inform contemporary debate on the subject of immigration.

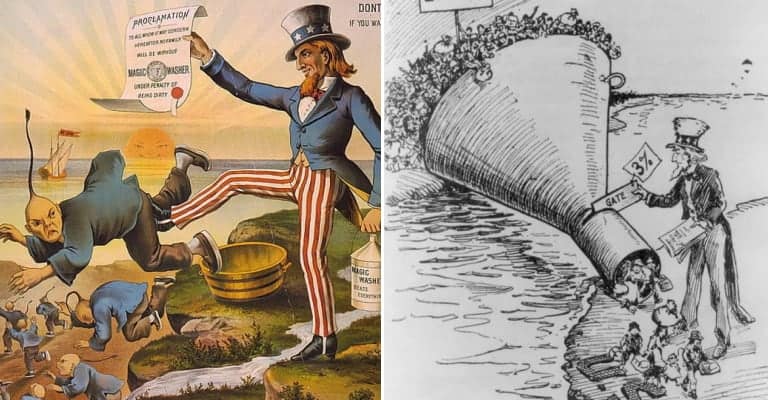

Here are 20 important moments of nativism in American history you should be aware of: